Climate and carbon cycle trends of the past 50 million years reconciled

2021-01-22

(Press-News.org) Predictions of future climate change require a clear and nuanced understanding of Earth's past climate. In a study published today in Science Advances, University of Hawai'i (UH) at Mānoa oceanographers fully reconciled climate and carbon cycle trends of the past 50 million years--solving a controversy debated in the scientific literature for decades.

Throughout Earth's history, global climate and the global carbon cycle have undergone significant changes, some of which challenge the current understanding of carbon cycle dynamics.

Less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere cools Earth and decreases weathering of rocks and minerals on land over long time scales. Less weathering should lead to a shallower calcite compensation depth (CCD), which is the depth in the ocean where the rate of carbonate material raining down equals the rate of carbonate dissolution (also called "snow line"). The depth of the CCD can be traced over the geologic past by inspecting the calcium carbonate content of seafloor sediment cores.

Former oceanography graduate student Nemanja Komar and professor Richard Zeebe, both at the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), applied the most comprehensive computer model of the ocean carbonate chemistry and CCD to date, making this the first study that quantitatively ties all the important pieces of the carbon cycle together across the Cenozoic (past 66 million years).

Contrary to expectations, the deep-sea carbonate records indicate that as atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) decreased over the past 50 million years, the global CCD deepened (not shoaled), creating a carbon cycle conundrum.

"The variable position of the paleo-CCD over time carries a signal of the combined carbon cycle dynamics of the past," said Komar, lead author of the study. "Tracing the CCD evolution across the Cenozoic and identifying mechanisms responsible for its fluctuations are therefore important in deconvolving past changes in atmospheric CO2, weathering, and deep-sea carbonate burial. As CO2 and temperature dropped over the Cenozoic, the CCD should have shoaled but the records show that it actually deepened."

Komar and Zeebe's computer model allowed them to investigate possible mechanisms responsible for the observed long-term trends and provide a mechanism to reconcile all the observations.

"Surprisingly, we showed that the CCD response was decoupled from changes in silicate and carbonate weathering rates, challenging the long-standing uplift hypothesis, which attributes the CCD response to an increase in weathering rates due to the formation of the Himalayas and is contrary to our findings," said Komar.

Their research suggests that the disconnect developed partially because of the increasing proportion of carbonate buried in the open ocean relative to the continental shelf due to the drop in sea level as Earth cooled and continental ice sheets formed. In addition, ocean conditions caused the proliferation of open-ocean carbonate-producing organisms during that period of time.

"Our work provides new insight into the fundamental processes and feedbacks of the Earth system, which is critical for informing future predictions of changes in climate and carbon cycling," said Komar.

The researchers are currently working on new techniques to constrain the chronology of climate and carbon cycle changes over the past 66 million years.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-22

Laser beams can be used to change the properties of materials in an extremely precise way. This principle is already widely used in technologies such as rewritable DVDs. However, the underlying processes generally take place at such unimaginably fast speeds and at such a small scale that they have so far eluded direct observation. Researchers at the University of Göttingen and the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen have now managed to film, for the first time, the laser transformation of a crystal structure with nanometre resolution and in slow motion in an electron microscope. The results have been published in the journal Science.

The ...

2021-01-22

Head and neck cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, and while effective treatments exist, sadly, the cancer often returns.

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati have tested a new combination therapy in animal models to see if they could find a way to make an already effective treatment even better.

Since they're using a Food and Drug Administration-approved drug to do it, this could help humans sooner than later.

These findings are published in the journal END ...

2021-01-22

Washington, DC - January 22, 2021 - New research shows that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduced both antibody and inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice. The study appears this week in the Journal of Virology, a publication of the American Society for Microbiology.

The research is important because "NSAIDs are arguably the most commonly used anti-inflammatory medications," said principal investigator Craig B. Wilen, Assistant Professor of Laboratory Medicine and Immunology, Yale University School of Medicine.

In addition to taking NSAIDs for chronic conditions such as arthritis, people take them "for shorter periods of time during infections, and [during] ...

2021-01-22

UPTON, NY - New results from an atmospheric study over the Eastern North Atlantic reveal that tiny aerosol particles that seed the formation of clouds can form out of next to nothingness over the open ocean. This "new particle formation" occurs when sunlight reacts with molecules of trace gases in the marine boundary layer, the atmosphere within about the first kilometer above Earth's surface. The findings, published in the journal Nature Communications, will improve how aerosols and clouds are represented in models that describe Earth's climate so scientists can understand how the particles--and the processes that control them--might ...

2021-01-22

Millions of students around the world could benefit if their educators adopted a more flexible and practical approach, say Swansea University experts.

After analysing the techniques current being used in higher education, the researchers are calling for a pragmatic and evidence-based approach instead.

Professor Phil Newton, director of learning and teaching at of Swansea University Medical School, said: "Higher education is how we train those who carry out important professional roles in our society. There are now more than 200 million students in HE worldwide and this number is likely to double again over the next decade.

"Given the size, impact, importance and cost of ...

2021-01-22

Researchers at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) in Argentina have found that, since the 1990s, up to 25% of reported bee species are no longer being reported in global records, despite a large increase in the number of records available. While this does not mean that these species are all extinct, it might indicate that these species have become rare enough that no one is observing them in nature. The findings appear January 22 in the journal One Earth.

"With citizen science and the ability to share data, records are going up exponentially, but the number of species reported in these records is going down," says first ...

2021-01-22

Although electric vehicles that reduce greenhouse gas emissions attract many drivers, the lack of confidence in charging services deters others. Building a reliable network of charging stations is difficult in part because it's challenging to aggregate data from independent station operators. But now, researchers reporting January 22 in the journal Patterns have developed an AI that can analyze user reviews of these stations, allowing it to accurately identify places where there are insufficient or out-of-service stations.

"We're spending billions ...

2021-01-22

On January 22 in Current Biology, a team of Harvard-led researchers presented the most complete genome yet assembled of one of the major Rafflesiaceae lineages, Sapria himalayana.

The species is found in Southeast Asia and its mottled red and white flower is about the size of a dinner plate. (It's more famous cousin, Rafflesia arnoldii, produces blossoms nearly three feet in diameter, the largest in the world.)

The genetic analysis revealed an astonishing degree of gene loss and surprising amounts of gene theft from its ancient and modern hosts. These findings bring unique perspectives into the number and kind of genes it takes to be an endoparasite (an organism that is completely dependent on its host for all nutrients), along ...

2021-01-22

What The Study Did: In this observational study, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection during a period of lockdown in southwest Germany was particularly low in children ages 1 to 10 years old. Overall, this large SARS-CoV-2 prevalence study in children is instructive for how ad hoc mass testing provides the basis for rational political decision-making in a pandemic setting.

Authors: Burkhard Tönshoff, M.D., of the University Children's Hospital in Heidelberg, Germany, and Klaus-Michael Debatin, M.D., of Ulm University Medical Center in Ulm, Germany, are the corresponding authors.

To ...

2021-01-22

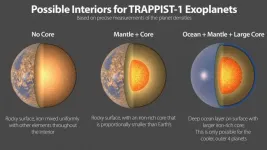

A new international study led by astrophysicist Eric Agol from the University of Washington has measured the densities of the seven planets of the exoplanetary system TRAPPIST-1 with extreme precision, the values obtained indicating very similar compositions for all the planets. This fact makes the system even more remarkable and helps to better understand the nature of these fascinating worlds. This study has just been published in the Planetary Science Journal.

The TRAPPIST-1 system is home to the largest number of planets similar in size to our Earth ever found outside our solar system. Discovered in 2016 by a research team led by Michaël Gillon, astrophysicist at the University of Liège, the system offers an insight into the immense ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Climate and carbon cycle trends of the past 50 million years reconciled