(Press-News.org) Our bodies send out hosts of signals - chemicals, electrical pulses, mechanical shifts - that can provide a wealth of information about our health.

But electronic sensors that can detect these signals are often made of brittle, inorganic material that prevents them from stretching and bending on our skin or within our bodies.

Recent technological advances have made stretchable sensors possible, but their changes in shape can affect the data produced, and many sensors cannot collect and process the body's faintest signals.

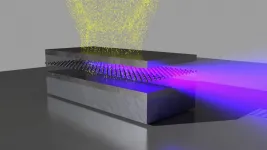

A new sensor design from the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) at the University of Chicago helps solve that problem. By incorporating a patterned material that optimizes strain distribution among transistors, researchers have created stretchable electronics that are less compromised by deformation. They also created several circuit elements with the design, which could lead to even more types of stretchable electronics.

The results were published in the journal Nature Electronics. Asst. Prof. Sihong Wang, who led the research, is already testing his design as a diagnostic tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a nervous system disease that causes loss of muscle control.

"We want to develop new kinds of electronics that can integrate with the human body," he said. "This new design allows electronics to stretch without compromising data and could ultimately help lead us to an out-of-clinic approach for monitoring our health."

Designing a pattern of stiffness

To design the electronics, the researchers used a patterned strain-distribution concept. When creating the transistor, they used substrates made of elastomer, an elastic polymer. They varied the density of the elastomer layers, meaning some remained softer, while others were stiffer while still elastic. The stiffer layers - termed "elastiff" by the researchers - were used for the active electronic areas.

The result was transistor arrays that had nearly the same electrical performance when they were stretched and bent as when they were undeformed. In fact, they had less than 5 percent performance variation when stretched with up to 100 percent strain.

They also used the concept to design and fabricate other circuit parts, including NOR gates, ring oscillators, and amplifiers. NOR gates are used in digital circuits, while ring oscillators are used in radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology. By making these parts successfully stretchable, the researchers could make even more complex electronics.

The stretchable amplifier they developed is among the first skin-like circuit that is capable of amplifying weak electrophysiological signals - down to a few millivolts. That's important for sensing the body's weakest signals, like those from muscles.

"Now we can not only collect signals, we can also process and amplify them right on the skin," Wang said. "That's a very important step for the future of electrophysiological sensing, when we can sense signals continuously."

A potential new diagnostic tool

Wang is already collaborating with a physician to test his design as a diagnostic tool for ALS. By measuring signals from muscles, the researchers hope to better diagnose the disease while gaining knowledge about how the disease affects the body.

They also hope to test their design in electronics that can be implanted within the body and create sensors for all kinds of bodily signals.

"With advancing designs, a lot of things that were previously impossible can now be done," Wang said. "We hope to not only help those in need, but also to take health monitoring out of the clinic, so patients can monitor their own signals in their everyday lives."

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the paper include Weichen Wang, Reza Rastak, Simiao Niu, Yuanwen Jiang, Prajwal Kammardi Arunachala, Yu Zheng Jie Xu, Naoji Matsuhisa, Xuzhou Yan, Masashi Miyakawa, Zhitao Zhang, Rui Ning, Amir M. Foudeh, Youngjun Yun, Christian Linder, Jeffrey B.-H. Tok and Zhenan Bao of Stanford University; Soon-Ki Kwon of Gyeongsang National University; and Yuto Ochiai of Yamagata University.

In the course of deciding whether to keep reading this article, you may change your mind several times. While your final choice will be obvious to an observer - you'll continue to scroll and read, or you'll click on another article - any internal deliberations you had along the way will most likely be inscrutable to anyone but you. That clandestine hesitation is the focus of research, published Jan. 20 in Nature, by Stanford University researchers who study how cognitive deliberations are reflected in neural activity.

These scientists and engineers developed a system that read and decoded the ...

URBANA, Ill. - Dairy producers know early nutrition for young calves has far-reaching impacts, both for the long-term health and productivity of the animals and for farm profitability. With the goal of increasing not just body weight but also lean tissue gain, a new University of Illinois study finds enhanced milk replacer with high crude-protein dry starter feed is the winning combination.

"Calves fed more protein with the starter had less fat in their body weight gain, and more protein was devoted to the development of the gastrointestinal system, compared with the lower ...

X-rays are usually difficult to direct and guide. X-ray physicists at the University of Göttingen have developed a new method with which the X-rays can be emitted more precisely in one direction. To do this, the scientists use a structure of thin layers of materials with different densities of electrons to simultaneously deflect and focus the generated beams. The results of the study were published in the journal Science Advances.

To generate X-rays in ordinary X-ray tubes, electrons that have been accelerated by a high voltage, collide with a metal anode. ...

Nature is full of colour. For flowers, displaying colour is primarily a means to attract pollinators. Insects use their colour vision not only to locate the right flowers to feed on but also to find mates. The evolutionary interaction between insects and plants has created complex dependencies that can have surprising outcomes. Casper van der Kooi, a biologist at the University of Groningen, uses an interdisciplinary approach to analyse the interaction between pollinators and flowers. In January, he was the first author of two review articles on this topic.

Bees and other insects visit flowers to feed on nectar and pollen. In exchange for ...

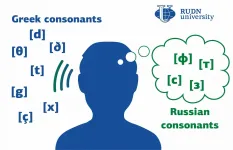

Linguists from RUDN University found out how Russian speakers differentiate between similar consonants of the Greek language and associate them with Russian sounds. The results of the study were published in the Speech Communication journal.

Efficient learning of a foreign language depends on a student's mother tongue and similarities between the sounds of the two languages. If they have a lot of similar sounds, foreign speech is perceived better, and if a student's mother tongue has no or few sounds similar to those of a foreign language, the progress will be slower. For example, it could be quite difficult for a Russian speaker to learn Greek, as some Greek consonants don't have Russian analogs. Linguists from RUDN University were the first to conduct a comprehensive ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- U.S. counties with higher income inequality faced higher rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths in the first 200 days of the pandemic, according to a new study. Counties with higher proportions of Black or Hispanic residents also had higher rates, the study found, reinforcing earlier research showing the disparate effects of the virus on those communities.

The findings, published last week by JAMA Network Open, were based on county-level data for all 50 states and Washington, D.C. Data sources included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USAFacts and the U.S. Census Bureau.

The lead author of the study, Tim Liao, head of the sociology department at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, initiated the study last summer after noticing that ...

When it launches in the mid-2020s, NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will explore an expansive range of infrared astrophysics topics. One eagerly anticipated survey will use a gravitational effect called microlensing to reveal thousands of worlds that are similar to the planets in our solar system. Now, a new study shows that the same survey will also unveil more extreme planets and planet-like bodies in the heart of the Milky Way galaxy, thanks to their gravitational tug on the stars they orbit.

"We were thrilled to discover that Roman will be able to offer even more information about the planets throughout our galaxy than originally planned," said Shota ...

Hitting a pothole on the road in just the wrong way might create a bulge on the tire, a weakened spot that will almost certainly lead to an eventual flat tire. But what if that tire could immediately begin reknitting its rubber, reinforcing the bulge and preventing it from bursting?

That's exactly what blood vessels can do after an aneurysm forms, according to new research led by the University of Pittsburgh's Swanson School of Engineering and in partnership with the Mayo Clinic. Aneurysms are abnormal bulges in artery walls that can form in brain arteries. Ruptured brain aneurysms are fatal in almost 50% of cases.

The research, recently published in Experimental Mechanics, is the first to show that there are two phases of wall restructuring after an aneurysm forms, the first ...

PHILADELPHIA (January 25, 2021) - While eating less and moving more are the basics of weight control and obesity treatment, finding ways to help people adhere to a weight-loss regimen is more complicated. Understanding what features make a diet easier or more challenging to follow can help optimize and tailor dietary approaches for obesity treatment.

A new paper from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing) analyzed different dietary approaches and clinical trials to better understand how to optimize adherence and subsequent weight reduction. The findings have been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"There is not convincing evidence that one diet is universally easier to adhere to than another for extended periods, a feature necessary for long-term ...

Research by an international team of medical experts has found cancer patients could be up to four times more likely to die following cancer surgery in low to lower-middle income countries than in high-income countries. It also revealed lower-income countries are less likely to have post-operative care infrastructure and oncology services.

The global observational study, published in The Lancet, explored global variation in post-operative complications and deaths following surgery for three common cancers. It was conducted by researchers from the GlobalSurg Collaborative and NIHR Global Health Unit on Global Surgery - led by the University of Edinburgh, with analysis and support from the University of Southampton.

Between April 2018 and January 2019, researchers enrolled 15,958 ...