(Press-News.org) Researchers from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKSUST) and the University of Hong Kong (HKU) recently demonstrated that the selectivity determinant of Origin Recognition Complex (ORC) for DNA binding lies in a 19-amino acid insertion helix in the Orc4 subunit, which is present in yeast but absent in human. Removal of this motif from Orc4 transforms the yeast ORC, which selects origins based on base-specific binding at defined locations, into one whose selectivity is dictated by chromatin landscape (genomic nucleosome profile), a characteristic feature shared by human ORC.

Further understanding of the preferred DNA shapes and nucleosome positioning requirements will provide new insights for the plasticity of the human ORC in selecting replication initiation sites during programmed development and disease transformation, and also help identify potential targets for anti-cancer drug screening and therapy design.

All living creatures, from simple unicellular yeast to complex multicellular human being, propagate through cell divisions. Each division requires the exact replication of the genome DNA, which is the blueprint of the identity of every organism. Over-replication may lead to cancers and under-replication may lead to developmental defects such as Meier-Gorlin syndrome. DNA replication is initiated at replication origins by ORC and other protein complexes assembled at these sites.

Interestingly, ORC is highly conserved in protein structure and function from yeast to human, but targets DNA sites that bear no obvious common features in these two systems. What causes this difference? This question had puzzled the scientists for decades.

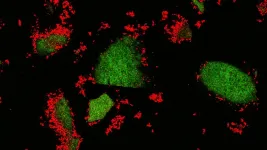

"Structure informs function," said Prof. Bik TYE, lead researcher and Senior Member of the Institute for Advanced Study, HKUST. "In 2018, we solved a high-resolution structure of the yeast ORC using cryo-electron microscopy. When we compared the structures between yeast and human, we found one important difference between them, which lies in one subunit of ORC--Orc4."

"The yeast Orc4 has an additional 19-amino acid motif which makes specific contacts with origin DNA and is not present in human," said Prof. Tye. "We immediately realized that this short motif of Orc4 might be a critical factor that causes the different behaviors of ORC in DNA binding between yeast and human. We then deleted this motif in yeast cells to test if it could convert the yeast ORC into one that behaves with human-like properties. Indeed, the engineered ORC in yeast behaves more like a human ORC, or as we call it, a humanized ORC."

DNA replication is one of the most fundamental processes in living cells. It is catalyzed by a similar set of replication machineries from yeast to human. In yeast cells, DNA replication starts from a set of sites, termed as replication origins. These sites share a specific DNA sequence, which can be recognized by a six-subunit protein complex known as origin recognition complex (ORC), Orc1-6. ORC binds to origin DNA, then serving as a platform to recruit Mcm2-7 helicase onto DNA. Mcm2-7 helicase is the machine responsible for separating double-stranded DNA to provide templates for DNA replication.

"The activities of each origin are tightly regulated to ensure genome integrity," said Prof. ZHAI Yuanliang, collaborator of the study and Assistant Professor at the School of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science at HKU. "Mis-regulation of replication initiation can cause either under- or over-replication of chromosomal DNA, which will induce DNA strand breaks, gross chromosomal rearrangements, and genome instability, a characteristic of almost all human cancers."

Inhibition of replication initiation is considered as an effective anti-cancer strategy for the selective killing of cancer cells through apoptosis while normal human cells arrest in G1 state (growth) or withdraw from the cell cycle into G0 state (inactive).

"Our studies lay a solid foundation to identify pairs of interactions, that are critical for origin recognition and helicase loading, with the potential as targets for anticancer drug screening and design," Prof. Zhai noted.

"This study demonstrates the power of multi-disciplinary approaches to answer fundamental questions in life sciences." commented Prof. Danny LEUNG, Assistant Professor at the Division of Life Science, HKUST, and Director of HKUST's Center for Epigenomics Research. Prof. Leung's team was responsible for the epigenomics and bioinformatic analyses of this study. The Center coordinates the efforts of the Hong Kong Epigenomics Project and facilitates regional researchers in carrying out epigenomic studies.

"It began with the atomic model of the yeast ORC bound to origin DNA and the discovery that a single motif in one of the subunits is responsible for the base-specific recognition of DNA by ORC. We conducted genome-wide assays and biochemical experiments to define binding characteristics, which led to the model that removal of this motif is the basis for the behavior of the human ORC, culminating in an insight for the evolution of ORC as eukaryotes adopt more complex genomic and epigenomic structures. This insight also bears critical information on disease transformation that is often associated with the plasticity of DNA replication," Prof. Leung observed.

INFORMATION:

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications on January 4, 2021.

Plants and other organisms can adapt their phenotypes to fluctuating environmental conditions within certain limits. The leaves of the dandelion, for example, are much more small in sunny locations than in shady places. In the sun, less leaf area is adequate to drive sufficient photosynthesis. This makes sense and is part of the dandelion's genetic programming.

However, plants can deviate from their normal programming if they are under constant heat stress or other extreme factors that endanger their survival. They then develop, for example, a wide range of leaf shapes that are extremely rare under natural conditions. In this case, scientists ...

Contracting COVID-19 while pregnant can have deadly consequences for the mother, a new study published today in END ...

Diabetics living in the UK worry about disruption to insulin supplies as a result of Brexit, new research shows.

Insulin is the hormone that helps control the body's blood sugar level and is critical to the survival of many people living with Type 1 diabetes. Currently most insulin used in the UK is imported.

The research - by the University of York - analysed 4,000 social media posts from the UK and the States in order to explore the experiences of living as an insulin-dependent person. Around 25 per cent of the posts relating to health were made by diabetics and about ...

Rapid, sensitive diagnosis of COVID-19 is essential for early treatment, contact tracing and reducing viral spread. However, some people infected with SARS-CoV-2 receive false-negative test results, which might put their and others' health at risk. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Nano Letters have developed ultra-absorptive nanofiber swabs that could reduce the number of false-negative tests by improving sample collection and test sensitivity.

Currently, the most sensitive test for COVID-19 involves using a long swab to collect a specimen from deep inside a patient's nose, and then using a method called reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA. But if the viral load is low, which can occur early in the course of infection, the swab ...

Widespread use of antibiotics in human healthcare and livestock husbandry has led to trace amounts of the drugs ending up in food products. Long-term consumption could cause health problems, but it's been difficult to analyze more than a few antibiotics at a time because they have different chemical properties. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry have developed a method to simultaneously measure 77 antibiotics in a variety of foods.

Antibiotics can be present at trace amounts in meat, eggs and milk if the animals aren't withdrawn from the drugs for a sufficient period of time before the products are collected. Also, ...

DALLAS, Jan. 27, 2021 -- Stroke survivors who completed a cardiac rehabilitation program focused on aerobic exercise, currently not prescribed to stroke survivors, significantly improved their ability to transition from sitting to standing, and how far they could walk during a six-minute walking test, according to new research published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access journal of the American Heart Association.

Cardiac rehabilitation is a structured exercise program prevalent in the U.S. for people with cardiovascular disease that has been shown to increase cardiovascular endurance and improve quality of life. Despite many similar ...

Tracking milk drinking in the ancient past is not straightforward. For decades, archaeologists have tried to reconstruct the practice by various indirect methods. They have looked at ancient rock art to identify scenes of animals being milked and at animal bones to reconstruct kill-off patterns that might reflect the use of animals for dairying. More recently, they even used scientific methods to detect traces of dairy fats on ancient pots. But none of these methods can say if a specific individual consumed milk.

Now archaeological scientists are increasingly ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers used single-molecule imaging to compare the genome-editing tools CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN. Their experiments revealed that TALEN is up to five times more efficient than CRISPR-Cas9 in parts of the genome, called heterochromatin, that are densely packed. Fragile X syndrome, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia and other diseases are the result of genetic defects in the heterochromatin.

The researchers report their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

The study adds to the evidence that a broader selection of genome-editing tools is needed to target all parts of the genome, said Huimin Zhao, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Illinois ...

A characteristic feature of all stem cells is their ability to self-renew. But how is this potential maintained throughout life? Scientists at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Heidelberg Institute for Stem Cell Technology and Experimental Medicine* (HI-STEM) have now discovered in mice that cells in the so-called "stem cell niche" are responsible for this: Blood vessel cells of the niche produce a factor that stimulates blood stem cells and thus maintains their self-renewal capacity. During aging, production of this factor ceases and blood stem cells begin to age.

Throughout life, blood stem cells in the bone marrow ensure that our body is adequately supplied with mature blood cells. If there is no current need for cell ...

Much of the earth's carbon is trapped in soil, and scientists have assumed that potential climate-warming compounds would safely stay there for centuries. But new research from Princeton University shows that carbon molecules can potentially escape the soil much faster than previously thought. The findings suggest a key role for some types of soil bacteria, which can produce enzymes that break down large carbon-based molecules and allow carbon dioxide to escape into the air.

More carbon is stored in soil than in all the planet's plants and atmosphere combined, and soil absorbs about 20% of human-generated carbon emissions. Yet, factors that affect carbon storage and release from soil have been challenging to study, placing limits on the relevance of ...