"People have different tendencies to engage in behavior that risks their health or that involve uncertainties about the future," says Gideon Nave, an assistant professor of marketing in Penn's Wharton School.

Yet explaining the origin of those tendencies, both in the genome and in the brain, has been challenging for researchers, partly because previous studies on the topic relied on small unrepresentative samples of college students. That has now changed.

In a massive study of brain scan and genetic data from more than 12,000 people, a team led by Nave and the University of Zurich's Gökhan Aydogan reveals how a genetic disposition toward risky behavior is embodied in the brain. Notably, these associations between risk-taking and brain anatomy are many. There is no one "risk region" in the brain, Nave says. "We find a lot of regions whose anatomy is altered in people who take risks."

The findings appear in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Many research teams have investigated the neuroanatomical correlates of the tendency to take risks across individuals, with recent studies identifying a number of associated brain regions. But these studies have been limited by their numbers--in the hundreds--constraining their power to make firm conclusions about the links between biology and behavior.

The current work benefits from a robust dataset, the UK Biobank, which has biomedical data from 500,000 volunteer participants between the ages of 40 and 69. To get an overall metric of risky behavior, the researchers looked at four self-reported behaviors: smoking, drinking, sexual promiscuity, and driving above the speed limit. These behavioral measures were aggregated to create an overall indicator of risk tolerance.

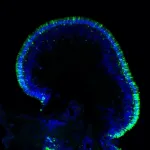

To drill down on the connections between genes, brain, and risk tolerance, the researchers used data of 12,675 people of European ancestry from the UK Biobank and began looking at relevant information. They first estimated the relationship between total gray matter volume across the brain and the risk-tolerance score.

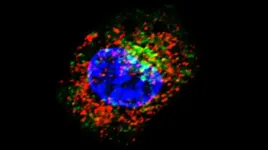

Even while controlling for a variety of factors--including total brain size, age, gender, handedness, excessive alcohol consumption, and genetic factors related to population structure--they found that higher risk tolerance was correlated with overall lower gray matter volume. Gray matter consists of most of the main cell bodies of neurons in the central nervous system and is understood to carry out the basic functions of the brain, including muscle control, sensory perception, and decision making.

The research team next took a closer look at which specific areas of the brain had the strongest relationship between risk taking and reduce gray matter. They identified associations with distinct brain regions that had been found in prior studies, such as the amygdala, involved in feelings of fear and emotion, which have also been shown to be activated in functional MRI studies of risky decision making. But they also found links between individuals' risky behavior and lower levels of gray matter in many additional brain regions that hadn't been implicated previously, such as the hippocampus, which is involved in creating new memories. They also found links in areas of the cerebellum, an area involved in balance and coordination whose involvement in cognition and decision-making has long been suspected, yet under-appreciated by researchers.

"We find that we don't have only one brain region that is the 'risk area,'" Nave says. "There are a lot of regions involved, and the effect sizes we found are not that large but also not that small."

Soon after the researchers had completed their initial analyses, the UK Biobank added brain scan images from more than 20,000 people to the database. This enabled the researchers to replicate their analysis in an additional 13,004 participants of European ancestry, finding almost all of the brain regions they originally identified as having a link between risk taking and reduced gray matter volume held.

"To do a study this large--more than 12,000 people, then replicated in 13,000 people--is really a new approach," says Philipp Koellinger from Vrej University Amsterdam, who was also involved in the research.

Finally the research team wanted to see if they could identify how participants' genetic disposition for risk behavior lined up with their neuroanatomy to try to draw a line between genes, brain, and behavior when it came to risk taking.

"This is not easy to do," Koellinger says. "We know that most behavioral traits have a complex genetic architecture, with a lot of genes that have small effects."

The researchers' solution to this "many genes" problem was to develop a measure of genetic variation they termed the polygenic risk score. They arrived at this metric through a genome-wide association study of a separate group of nearly 300,000 people of European ancestry, taking into account the effects of more than a million single nucleotide polymorphisms, or places where one "letter" of DNA differed from person to person, that were associated with risky behavior.

This risk score, the team found, explained 3% of the variation in risky behavior. The score also correlated with reduced gray matter volume in three specific brain areas. Looking at these three brain regions, they determined that differences in the gray matter of these locactions in the brain carried out around 2.2% of genetic disposition toward risky behavior.

"It appears that grey matter of these three regions is translating a genetic tendency into actual behavior," Koellinger says.

While the study makes great strides to link up genes, brain anatomy, and behavior, it also generates many additional unanswered questions.

For example, the fact that these brain regions explained only 2.2% of the genetic disposition, the researchers say, points to the fact that genes that support risk tolerance may be related to aspects of biology besides what happens in the brain. "The question then is, What are they related to?" Nave says.

Nave emphasizes that further study is needed to clarify genetic disposition from environmental effects.

"You want to think about the fact that there are family, environment, and genetic effects, and there is also the correlation between all these factors," Nave says. "Genetics and environment, genetics and family--even what appears to be a genetic effect could actually be a nurture effect because you inherit your parents' genes.

"For instance," he says, "if your parents are more nurturing, and they have genes related to more nurturing behavior and if nurturing affects your behavior, you will see genes and behavior correlated, but that doesn't mean that the genes directly caused the behavior," he says.

Nave is hopeful that a new collaboration he launched, the Brain Imaging and Genetics in Behavioral Research, or BIG BEAR, Consortium, members of which conducted the current study, will help in finding answers to these questions. "Our ultimate goal is teasing apart all of these relationships and identifying the causal relationships," Nave says.

INFORMATION:

Gideon Nave is the Carlos and Rosa de la Cruz Assistant Professor in the Wharton School Department of Marketing at the University of Pennsylvania.

Nave's coauthors were Remi Daviet of Penn's Wharton School; Joseph Kable of Penn's School of Arts & Sciences; Henry R. Krazler of Penn's Perelman School of Medicine; Gökhan Aydogan, Todd A. Hare, and Christian C. Ruff of the University of Zurich; and Richard Karlsson Linnér and Philipp D. Koellinger of Vrjie Universiteit Amsterdam. Aydogan was the first author, and Nave was the senior and corresponding author.

Funding for the study came from the National Science Foundation (Grant 1942917), Wharton School Dean's Research Fund, European Research Council, the Swiss National Science Foundation, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant AA023894), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant DA046345).