(Press-News.org) EAST LANSING, Mich. - For Michigan State University's Felicia Wu, the surprise isn't that people who work with livestock are at higher risk of picking up antibiotic-resistant bacteria, but instead how much higher their risk levels are.

"This is a bit of a wakeup call," said Wu, John. A Hannah Distinguished Professor in the Departments of Food Science and Human Nutrition and Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics. "I don't think there was much awareness that swine workers are at such high risk, for example. Or that large animal vets are also at extremely high risk."

Compared with individuals who don't work with animals, those working on swine farms are more than 15 times more likely to harbor a particular strain of a bacterium known as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, acquired from livestock. For cattle workers, that number is nearly 12. For livestock veterinarians, it approaches eight.

Wu and Chen Chen, a research assistant professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, published their findings, along with the risk factors for other related professions, in the journal Occupational & Environmental Medicine. Their paper highlights these elevated risks, what farmers can do to protect themselves and what we understand about the public health burden posed by livestock-associated MRSA.

"Livestock-associated MRSA is a strain of MRSA that is especially infectious among animals. Now it has evolved to infect humans as well," said Wu, who was recently named a fellow of the Society for Risk Analysis. "Bacteria have shown an amazing ability to jump across species to colonize and cause infections."

Livestock-associated MRSA is a zoonotic disease, a disease that can transmit between animals and humans. Such diseases can have devastating consequences for human health. The novel coronavirus pandemic, for example, was caused by a virus that likely originated in bats.

Although the novel coronavirus and livestock-associated MRSA work and spread in different ways, they both are a reminder that when people understand the risks posed by such diseases, they do have some power to minimize them. For example, good hygienic practices and policies supported by science can make meaningful differences, especially in the case of livestock-acquired MRSA, Wu said.

"The final message is that we need to protect our health and the health of our animals," she said. "We don't have control over bats, but we do have some level of control over how we raise and handle our poultry, cattle and swine."

Although it's possible to carry MRSA without it becoming a problem, the bacteria can cause serious infections when given the chance. Livestock-associated MRSA was first documented in the early 2000s and appears to be less dangerous to humans than MRSA that evolved in health care settings, where it built up defenses against a range of antibiotics.

The livestock-associated strain also appears to be less prevalent than community-associated MRSA, caused by bacteria lurking in gyms, schools and workplaces, which are typically more treatable than their counterparts found in hospitals and doctors' offices.

For these reasons, livestock-associated MRSA doesn't garner as much attention as other strains, but there's still much to learn about the bacteria from livestock and their impact on human health, Wu said. When she first came to MSU in 2013, she became interested in how the growing problem of antibiotic resistance was being influenced by bacteria that jumped to humans from livestock.

"We don't understand how much of that problem we have in human populations," said Wu. "This particular paper is trying understand one aspect of that."

To calculate the risk levels of acquiring livestock-associated MRSA, Wu and Chen combed through 15 years of published literature, extracting data about the likelihood of people acquiring the bacteria based on their livestock-related profession. The risk was elevated for every occupation they studied: vets, slaughterhouse employees and people who worked with swine, horses, cattle and poultry.

But there is also positive news to share along with the unsettling risk numbers. In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration introduced rules and monitoring programs to curb the use of antibiotics. Farmers can still use antibiotics to treat and prevent disease, but the agency forbid the use of antibiotics to spur animal growth. This has reduced the pressure on bacteria in agriculture settings to evolve resistance to antibiotics.

There are also a number of straightforward precautions individuals can take to help protect themselves and their animals. MRSA lives on soft tissue -- on people's skin and in their noses -- and can do so without causing harm when that tissue is intact. Reducing exposure of broken skin to the environment by keeping cuts and open wounds clean and covered can help reduce the risk of infection. Other simple steps, like regular hand-washing along with wearing gloves and protective clothing, can also stem the spread of livestock-acquired MRSA.

"Once the bacteria get a hold in an environment, they are really, really hard to get rid of," said Wu. "Reducing the risk of antibiotic-resistant infections is one of the main goals that farmers have"

INFORMATION:

(Note for media: In online coverage, please include a link to the original paper published online in October 2020: https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-106418)

Michigan State University has been working to advance the common good in uncommon ways for 160 years. One of the top research universities in the world, MSU focuses its vast resources on creating solutions to some of the world's most pressing challenges, while providing life-changing opportunities to a diverse and inclusive academic community through more than 200 programs of study in 17 degree-granting colleges.

For MSU news on the Web, go to MSUToday. Follow MSU News on Twitter at twitter.com/MSUnews.

The increased global use of antiviral and antiretroviral medication could have a detrimental impact on crops and potentially heighten resistance to their effects, new research has suggested.

Scientists from the UK and Kenya found that lettuce plants exposed to a higher concentration of four commonly-used drugs could be more than a third smaller in biomass than those grown in a drug-free environment.

They also examined how the chemicals transferred throughout the crop and found that, in some cases, concentrations were as strong in the leaves as they were in the roots.

The study - published in Science of the Total Environment - was conducted by environmental chemists from the University of Plymouth (UK), Kisii University (Kenya) and ...

An international team of researchers has characterized the effect and molecular mechanisms of an amino acid change in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein N439K. Viruses with this mutation are both common and rapidly spreading around the globe. The peer reviewed version of the study appears January 25 in the journal Cell.

Investigators found that viruses carrying this mutation are similar to the wild-type virus in their virulence and ability to spread but can bind to the human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor more strongly. Importantly, researchers show that this mutation confers resistance to some individual's serum antibodies and against many neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, including one that is part of a treatment authorized for emergency use by the U.S. ...

The multidisciplinary research group Lactiker - Quality and Safety of Foods from Animal Origin, which is attached to the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), is working on (among other things) characterising the biochemical, microbiological and technological processes involved in cheese manufacturing that have a direct impact on its technological, nutritional and sensory quality, as well as on its food safety status. The aim is to provide the cheesemaking industry with the information it requires to ensure safe, high-quality products.

The group, which has been working in this field for 25 years, has conducted studies focusing on all aspects of the production of cheeses under the Idiazabal Protected Designation of Origin ...

More effective antiviral treatments could be on the way after research from The University of Texas at Austin sheds new light on the COVID-19 antiviral drug remdesivir, the only treatment of its kind currently approved in the U.S. for the coronavirus.

The study is END ...

BOSTON - Investments in infrastructure to promote bicycling and walking could save as many as 770 lives and $7.6 billion each year across 12 northeastern states and the District of Columbia under the proposed Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI), according to a new Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health study.

Published in the Journal of Urban Health, the analysis shows that the monetary benefit of lives saved from increased walking and cycling far exceed the estimated annual investment for such infrastructure, without ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Malaria is an ancient scourge, but it's still leaving its mark on the human genome. And now, researchers have uncovered recent traces of adaptation to malaria in the DNA of people from Cabo Verde, an island nation off the African coast.

An archipelago of ten islands in the Atlantic Ocean some 385 miles offshore from Senegal, Cabo Verde was uninhabited until the mid-1400s, when it was colonized by Portuguese sailors who brought enslaved Africans with them and forced them to work the land.

The Africans who were forcibly brought to Cabo Verde carried ...

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Many molecules in our bodies help our immune system keep us healthy without overreacting so much that our immune cells cause problems, such as autoimmune diseases. One molecule, called AIM2, is part of our innate immunity - a defense system established since birth - to fight pathogens and keep us healthy. But little was known about AIM2's contribution to T cell adaptive immunity - defenses developed in response to particular pathogens and health problems we develop over the course of our lives.

Now, UNC School of Medicine scientists led by Jenny Ting, PhD, the William Kenan Distinguished Professor of Genetics, and Yisong Wan, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology, discovered that AIM2 is important for the proper function of regulatory ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- When their manhood is threatened, some men respond aggressively, but not all. New research from Duke University suggests who may be most triggered by such threats - younger men whose sense of masculinity depends heavily on other people's opinions.

"Our results suggest that the more social pressure a man feels to be masculine, the more aggressive he may be," said Adam Stanaland, a Ph.D. candidate in psychology and public policy at Duke and the study's lead author.

"When those men feel they are not living up to strict gender norms, they may feel the need to act aggressively to prove their manhood -- to 'be a man'."

The pair of studies considered 195 undergraduate students and a random pool of 391 men ages 18 to 56.

Study participants were asked a series ...

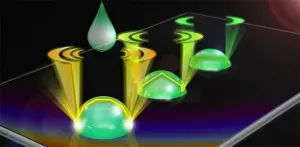

Tiny molecular forces at the surface of water droplets can play a big role in laser output emissions. As the most fundamental matrix of life, water drives numerous essential biological activities, through interactions with biomolecules and organisms. Studying the mechanical effects of water-involved interactions contributes to the understanding of biochemical processes. According to Yu-Cheng Chen, professor of electronic engineering at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), "As water interacts with a surface, the hydrophobicity at the bio-interface mainly determines the mechanical equilibrium ...

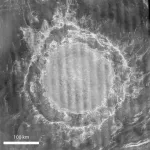

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- At some point between 300 million and 1 billion years ago, a large cosmic object smashed into the planet Venus, leaving a crater more than 170 miles in diameter. A team of Brown University researchers has used that ancient impact scar to explore the possibility that Venus once had Earth-like plate tectonics.

For a study published in Nature Astronomy, the researchers used computer models to recreate the impact that carved out Mead crater, Venus's largest impact basin. Mead is surrounded by two clifflike faults -- rocky ripples frozen in time after the basin-forming impact. The models showed that for those rings to be where they ...