A small protein in bacteria overlooked up to now

2021-01-29

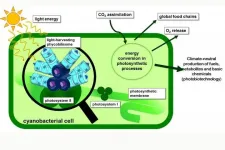

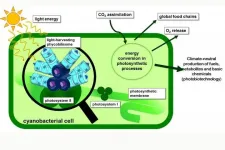

(Press-News.org) The biological process of photosynthesis is found at the beginning of nearly all food chains. It produces oxygen to breathe and provides the energetic foundation for using biotechnological processes to synthesize biofuels and chemical feedstock. Therefore, researchers are particularly interested in rapidly growing cyanobacteria. These organisms use light as an energy source and can carry out photosynthesis, similar to plants. However, the required photosynthetic protein complexes bind many nutrients. Vanessa Krauspe and Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hess from the working group for Genetics & Experimental Bioinformatics of the Faculty of Biology of the University of Freiburg and their collaborators have discovered the small, previously unknown protein NblD, which is involved in the recycling of these nutrients. The researchers are presenting their new findings in the specialist journal PNAS.

In addition to the pigment chlorophyll, cyanobacteria use for photosynthesis frequently also phycobilisomes, complexes consisting of proteins and another class of tetrapyrrole pigments, which are considered as the most effective light-harvesting structures found in nature. However, using phycobilisomes is costly for the cell as they bind a huge amount of nutrients in their macromolecular structures - nitrogen in particular. In order to recycle these nutrients under scarcity conditions, for example under conditions of insufficient nitrogen supplies, the cyanobacteria have sophisticated genetic programs which, among scientists, are actually considered to be well-examined.

In a new approach, aiming at taking a closer look at especially small genes and proteins, the team at the University of Freiburg has been able to characterize NblD. It is a previously unknown small protein with high-affinity, meaning it rapidly forms bonds. NblD binds specifically to what is known as the phycocyanin beta-subunit of the phycobilosome. Through this process cyanobacterial cells receive special mechanisms to handle potentially dangerous intermediate products that occur during the recycling of the phycobilisomes. Hess says, "The results illustrate the fact that especially small genes and proteins have been neglected hitherto and deserve a closer look."

INFORMATION:

The team of Krauspe and Hess accomplished the new findings in cooperation with Prof. Dr. Oliver Schilling of the University Medical Center Freiburg, Prof. Dr. Boris Maček of the University of Tübingen, and Prof. Dr. Nicole Frankenberg-Dinkel of the Technical University of Kaiserslautern.

The work has been supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the priority program (SPP) 2002 "Small Proteins in Prokaryotes, an Unexplored World", the research training group (GRK) 2344 "MeInBio - BioInMe: Exploration of spatio-temporal dynamics of gene regulation using high-throughput and high-resolution methods", as well as the research group (FOR) 2816 "The Autotrophy-Heterotrophy Switch in Cyanobacteria: Coherent Decision-Making at Multiple Regulatory Layers (SCyCode)."

Original publication:

Krauspe V., Fahrner M., Spät P., Macek B., Schilling O., Hess W.R. (2021): Discovery of a small protein factor involved in the coordinated degradation of phycobilisomes in cyanobacteria. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, Vol. 118, No. 5 e2012277118; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2012277118.

Contact:

Institute of Biology III

Faculty of Biology

University of Freiburg

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-29

Who hasn't at some point been chewing on an almond and tasted an unpleasant and unexpected aftertaste that has nothing to do with the taste we are used to from one of the most consumed nuts in the world? The culprit has a name: amygdalin, a diglucoside that, when in contact with enzymes present in saliva, breaks down into glucose, benzaldehyde (the cause of the bitter taste) and hydrogen cyanide.

To reduce this unpleasant 'surprise', the Farming Systems Engineering (AGR-128) and Food Technology (AGR-193) research groups at the University of Cordoba's School of Agricultural and Forestry Engineering, ...

2021-01-29

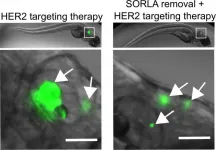

SORLA is a protein trafficking receptor that has been mainly studied in neurons, but it also plays a role in cancer cells. Professor Johanna Ivaska's research group at Turku Bioscience observed that SORLA functionally contributes to the most reported therapy-resistant mechanism by which the cell-surface receptor HER3 counteracts HER2 targeting therapy in HER2-positive cancers. Removing SORLA from cancer cells sensitized anti-HER2 resistant breast cancer brain metastasis to targeted therapy.

HER2 protein is a strong driver of tumor growth. HER2 amplification occurs ...

2021-01-29

High-intensity tropical cyclones have been moving closer to coasts over the past 40 years, potentially causing more destruction than before.

The trend of tropical cyclones - commonly known as hurricanes or typhoons - increasingly moving towards coasts over the past 40 years appears to be driven by a westward shift in their tracks, say the study's authors from Imperial College London.

While the underlying mechanisms are not clear, the team say it could be connected to changes in tropical atmospheric patterns possibly caused by climate change. The research is published today in Science.

Globally, 80 to 100 cyclones develop over tropical oceans each year, impacting regions in the Pacific, ...

2021-01-29

New research by Mimi E. Lam (University of Bergen) just published in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications identifies and explores the impacts of salient viral or COVID-19 behavioural identities that are emerging.

"These emergent COVID-19 behavioural identities are being hijacked by existing social and political identities to politicize the pandemic and heighten racism, discrimination, and conflict," says Lam. She continues: "the COVID-19 pandemic reminds us that we are not immune to each other. To unite in our fight against the pandemic, it is important to recognize the basic dignity of all and value the human diversity currently dividing us."

"Only ...

2021-01-29

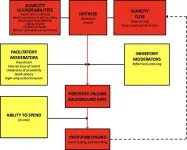

Drawing on animal-foraging theory, a new model predicts psychological factors that may lead to panic buying during times of crisis. The model is largely supported by real-world data from the COVID-19 pandemic. Richard Bentall of the University of Sheffield, England, and colleagues presented these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on January 27.

In the early stages of the pandemic, consumers in several countries around the world engaged in "panic buying" of household items, causing temporary shortages of toilet rolls and other products. Such behavior is typical during times of crisis, but few studies have examined the psychology of crisis-driven over-purchasing.

To better understand this phenomenon, Bentall and colleagues turned to animal-foraging ...

2021-01-29

As one of the most experienced archaeologists studying California's Native Americans, Lynn Gamble(link is external) knew the Chumash Indians had been using shell beads as money for at least 800 years.

But an exhaustive review(link is external) of some of the shell bead record led the UC Santa Barbara professor emerita of anthropology to an astonishing conclusion: The hunter-gatherers centered on the Southcentral Coast of Santa Barbara were using highly worked shells as currency as long as 2,000 years ago.

"If the Chumash were using beads as money 2,000 years ago," Gamble said, "this changes our thinking of hunter-gatherers and sociopolitical and economic complexity. This may be the first example of the use of money anywhere in the ...

2021-01-29

As part of standard patient protocol, doctors inform women of the risks of pregnancy. But there is one exception to this standard: stillbirth.

University of Arkansas law professor Jill Wieber Lens argues that women have a right to know of the risk of stillbirth, and, consistent with the evolution of informed consent law, this right should be enforceable through a medical malpractice tort claim.

Stillbirth, or pregnancy loss after 20 weeks but before birth, is not uncommon. Annually, 26,000 U.S. women give birth to a stillborn baby, or roughly one out every 160 pregnancies. The United States' stillbirth rate ...

2021-01-29

COLLEGE PARK, Md.--The amount of methane released into the atmosphere as a result of coal mining is likely much higher than previously calculated, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union recently.

The study estimates that methane emissions from coal mines are approximately 50 percent higher than previously estimated. The research was done by a team at the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and others.

The higher estimate is due mainly to two factors: methane that continues to be emitted from thousands of abandoned mines and the higher methane content in coal seams that are ever deeper, according to chief ...

2021-01-29

The Japanese now have their own reference genome thanks to researchers at Tohoku University who completed and released the first Japanese reference genome (JG1).

Their study was published in the journal Nature Communications on January 11, 2021.

"JG1 can aid with the clinical sequence analysis of Japanese individuals with rare diseases as it eliminates the genomic differences from the international reference genome," said Jun Takayama, co-author of the study.

Back in 2003, the Human Genome Project, through a gargantuan global effort, cracked the code of life and mapped all the genes of the human genome.

Since then, more accurate versions of the human reference genome have ...

2021-01-29

The researchers of the Institute for Atmospheric and Earth system research at the University of Helsinki have investigated how atmospheric particles are formed in the Arctic. Until recent studies, the molecular processes of particle formation in the high Arctic remained a mystery.

During their expeditions to the Arctic, the scientists collected measurements for 12 months in total. The results of the extensive research project were recently published in the Geophysical Research Letters journal.

The researchers discovered that atmospheric vapors, particles, and cloud formation have clear differences within various Arctic environments. The study clarifies how Arctic warming and sea ice loss strengthens processes where different vapors are emitted to the atmosphere. The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A small protein in bacteria overlooked up to now