By changing their shape, some bacteria can grow more resilient to antibiotics

2021-01-29

(Press-News.org) New research led by Carnegie Mellon University Assistant Professor of Physics Shiladitya Banerjee demonstrates how certain types of bacteria can adapt to long-term exposure to antibiotics by changing their shape. The work was published this month in the journal Nature Physics.

Adaptation is a fundamental biological process driving organisms to change their traits and behavior to better fit their environment, whether it be the famed diversity of finches observed by pioneering biologist Charles Darwin or the many varieties of bacteria that humans coexist with. While antibiotics have long helped people prevent and cure bacterial infections, many species of bacteria have increasingly been able to adapt to resist antibiotic treatments.

Banerjee's research at Carnegie Mellon and in his previous position at the University College London (UCL) has focused on the mechanics and physics behind various cellular processes, and a common theme in his work has been that the shape of a cell can have major effects on its reproduction and survival. Along with researchers at the University of Chicago, he decided to dig into how exposure to antibiotics affects the growth and morphologies of the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus, a commonly used model organism.

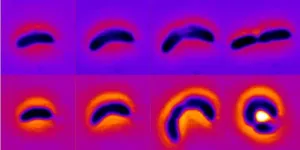

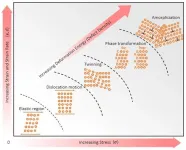

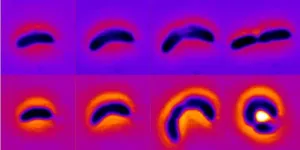

"Using single-cell experiments and theoretical modelling, we demonstrate that cell shape changes act as a feedback strategy to make bacteria more adaptive to surviving antibiotics," Banerjee said of what he and his collaborators found.

When exposed to less than lethal doses of the antibiotic chloramphenicol over multiple generations, the researchers found that the bacteria dramatically changed their shape by becoming wider and more curved.

"These shape changes enable bacteria to overcome the stress of antibiotics and resume fast growth," Banerjee said. The researchers came to this conclusion by developing a theoretical model to show how these physical changes allow the bacteria to attain a higher curvature and lower surface-to-volume ratio, which would allow fewer antibiotic particles to pass through their cellular surfaces as they grow.

"This insight is of great consequence to human health and will likely stimulate numerous further molecular studies into the role of cell shape on bacterial growth and antibiotic resistance," Banerjee said.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study included Aaron R. Dinner, Klevin Lo and Norbert F. Scherer from the University of Chicago; and Nikola Ojkic and Roisin Stephens, previous members of the Banerjee research group at UCL.

Funding for the research was provided by grants from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council of the United Kingdom (EP/R029822/1), the Royal Society University Research Fellowship (URF/R1/180187), the Royal Society (RGF/EA/181044) and the National Science Foundation (NSF PHY-2020295, NSF PHY-1305542, NSF DMR-1420709, MCB-1953402).

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-29

School closures during COVID-19 have decreased access to school meals, which is likely to increase the risk for food insecurity among children in Maryland, according to a new report issued by researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM). The number of meals served to school-age children during the first three months of the pandemic dropped by 58 percent, compared to the number of free or reduced-price meals served the previous spring. As a result, thousands of children across the state were placed at increased risk of food insecurity, with many likely experiencing the health ramifications ...

2021-01-29

Boulder, Colo., USA: GSA's dynamic online journal, Geosphere, posts articles online regularly. Topics for articles posted for Geosphere this month include feldspar recycling in Yosemite National Park; the Ragged Mountain Fault, Alaska; the Khao Khwang Fold and Thrust Belt, Thailand; the northern Sierra Nevada; and the Queen Charlotte Fault.

Feldspar recycling across magma mush bodies during the voluminous Half Dome and Cathedral Peak stages of the Tuolumne intrusive complex, Yosemite National Park, California, USA

Louis F. Oppenheim; Valbone Memeti; Calvin G. Barnes; Melissa Chambers; Joachim Krause ...

Abstract: Incremental pluton growth can produce sheeted complexes with no magma-magma interaction or large, dynamic magma bodies communicating via crystal and melt exchanges, depending ...

2021-01-29

Washington, DC — Blood pressure that remains elevated over of time — known as chronic hypertension — has been linked to heart disease, which is the leading cause of death in the United States. Recent research has shown that persistent high blood pressure may also increase the risk for stroke and overall mortality. Yet, only about 1 in 4 adults with chronic hypertension have their condition under control, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a new study to be presented today at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine's (SMFM) annual meeting, The Pregnancy Meeting™, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh will unveil findings that suggest that women who develop high blood pressure during pregnancy and who continue ...

2021-01-29

News reports indicate COVID-19 vaccines are not getting out soon enough nor in adequate supplies to most regions, but there may be a larger underlying problem than shortages. A University of California, Davis, study found that more than a third of people nationwide are either unlikely or at least hesitant to get a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available to them.

The results are from public polling of more than 800 English-speaking adults nationwide in a study published online earlier this month in the journal Vaccine.

"Our research indicates that vaccine uptake will be suboptimal ... with 14.8 percent of respondents being unlikely to get vaccinated ...

2021-01-29

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- The most powerful substance in the human brain for neuronal communication is glutamate. It is by far the most abundant, and it's implicated in all kinds of operations. Among the most amazing is the slow restructuring of neural networks due to learning and memory acquisition, a process called synaptic plasticity. Glutamate is also of deep clinical interest: After stroke or brain injury and in neurodegenerative disease, glutamate can accumulate to toxic levels outside of neurons and damage or kill them.

Shigeki Watanabe of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, a familiar face at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) as a faculty member and researcher, is hot on the ...

2021-01-29

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- When we step on the car brake upon seeing a red traffic light ahead, a sequence of events unfolds in the brain at lightning speed.

The image of the traffic light is transferred from our eyes to the visual cortex, which, in turn, communicates to the premotor cortex -- a section of the brain involved in preparing and executing limb movements. A signal is then sent to our foot to step on the brake. However, brain region that helps the body go from "seeing" to "stepping" is still a mystery, frustrating neuroscientists and psychologists.

To unpack this "black box," a team of neuroscientists at the University of California, Riverside, has ...

2021-01-29

A new report combining forecasting and expert prediction data, predicts that 125,000 lives could be saved by the end of 2021 if 50% or more of the U.S. population initiated COVID vaccination by March 1, 2021.

"Meta and consensus forecast of COVID-19 targets," developed by Thomas McAndrew, a computational scientist and faculty member at Lehigh University's College of Health, and colleagues, incorporates data from experts and trained forecasters, combining their predictions into a single consensus forecast. In addition McAndrew and his team produce a metaforecast, which is a combination of an ensemble of computational models and their consensus forecast.

In addition to predictions related to the impact of vaccinations, ...

2021-01-29

Researchers at Linköping University, Sweden, have developed a proton trap that makes organic electronic ion pumps more precise when delivering drugs. The new technique may reduce drug side effects, and in the long term, ion pumps may help patients with symptoms of neurological diseases for which effective treatments are not available. The results have been published in Science Advances.

Approximately 6% of the world's population suffer from neurological diseases such as epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and chronic pain. However, currently available drug delivery methods - mainly tablets and injections - place the drug in locations where it is not required. This can lead to side effects ...

2021-01-29

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- In many ways, our brain and our digestive tract are deeply connected. Feeling nervous may lead to physical pain in the stomach, while hunger signals from the gut make us feel irritable. Recent studies have even suggested that the bacteria living in our gut can influence some neurological diseases.

Modeling these complex interactions in animals such as mice is difficult to do, because their physiology is very different from humans'. To help researchers better understa nd the gut-brain axis, MIT researchers have developed an "organs-on-a-chip" system that replicates interactions between the brain, liver, and colon.

Using that system, the researchers were able to model the influence that microbes living in the gut have on both healthy brain tissue and tissue samples derived ...

2021-01-29

An international team of researchers produced islands of amorphous, non-crystalline material inside a class of new metal alloys known as high-entropy alloys.

This discovery opens the door to applications in everything from landing gears, to pipelines, to automobiles. The new materials could make these lighter, safer, and more energy efficient.

The team, which includes researchers from the University of California San Diego and Berkeley, as well as Carnegie Mellon University and University of Oxford, details their findings in the Jan. 29 issue of Science Advances.

"These present ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] By changing their shape, some bacteria can grow more resilient to antibiotics