European hibernating bats cope with white-nose syndrome which kills North American bats

2021-02-03

(Press-News.org) What are the reasons for such a contrast in outcomes? A scientist team led by the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) has now analysed the humoral innate immune defence of European greater mouse-eared bats to the fungus. In contrast to North American bats, European bats have sufficient baseline levels of key immune parameters and thus tolerate a certain level of infection throughout hibernation. The results are published in the journal "Developmental and Comparative Immunology".

During infections caused by Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), North American bats arouse frequently from hibernation to trigger a more elaborate immune response, whereas European bats remain dormant, owing, as the new results reveal, to their competent baseline immunity. Not being able to deal with the fungus by baseline immunity causes North American bats to deplete fat stores before the end of winter bnecause of the need for additional and energetically expensive arousals, which ultimately leads to their starvation. European bats may also arouse once in a while when infected but their strong baseline immunity allows them to balance the tight energy budget better during winter hibernation.

For this investigation, the scientists went to hibernation sites in Germany and studied 61 mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis) with varying levels of natural infections by Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The animals were divided into three groups according to the severity of fungal infections (asymptomatic, mild symptoms, severe infection). Body mass and skeletal body size of bats was measured and blood samples taken from torpid animals. In addition, the team monitored in other conspecifics how often infected animals arose from hibernation. "We could show that there is no link between infection and the frequency of waking up from hibernation in the European greater mouse-eared bat," say Marcus Fritze and Christian C. Voigt, bat experts from the Department Evolutionary Ecology at Leibniz-IZW. "This is consistent with the idea that the fungus does not trigger an immune response in European hibernating bats but is rather kept under control by the bats' baseline immunity."

In contrast, North American bats such as little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) arouse frequently when infected by the fungus to elicit an immune response. Frequent arousal and the immune response require energy and prematurely deplete the body's fat stores before the winter has ended. The protein haptoglobin seems key in the bats' fight against the fungus. Haptoglobin is an acute phase protein, which can be produced by bats without large metabolic costs. "Our results demonstrated the central role of haptoglobin in the defence against the fungus. Interestingly, baseline levels of this protein are sufficient to protect the European host against the fungus and there is no need to actively synthesise the protein during the torpid phase", adds Gábor Á. Czirják, wildlife immunologist at the Department of Wildlife Diseases of the Leibniz-IZW.

A second key finding of the team's investigation is that heavier European greater mouse-eared bats arouse from hibernation more frequently than lean conspecifics. This seems counterintuitive because each arousal event causes a depletion of fat stores. Well-nourished bats seem to assist their immune system by actively clearing off the external fungal hyphens from their body while being awake for short periods. Thus, heavy bats are in a healthier condition towards the end of hibernation than lean animals. Lean animals cannot afford to arouse as often and thus depend on the efficacy of the baseline immunity to control the fungus. The safety net of a competent immunity keeps European (and Asian) bats alive during infections with P. destructans but proves to be insufficient for North American bats.

These results add further evidence that there are differences in the defence strategies against the causative agent of white-nose syndrome in European and North American bat species. Tolerance strategies aim to limit the impact of the fungal infection on the health of animals. Resistance strategies, on the other hand, try to actively reduce the load of pathogens. "Tolerance strategies are effective, as the immune defences of hibernating European mouse-eared bats show," Voigt summarises. "In North American bats, however, this ability is not present to a sufficient degree, possibly because the Pd fungus originated in Europe, giving European species a head start in developing efficient defence mechanisms."

INFORMATION:

Publication

Fritze M, Puechmaille SJ, Costantini D, Fickel J, Voigt CC, Czirják GÁ (2021): Determinants of defence strategies of a hibernating European bat species towards the fungal pathogen Pseudogymnoascus destructans. DEVEL COMP IMMUNOL 119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2021.104017

Contact

Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) in the Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V.

Alfred-Kowalke-Str. 17

10315 Berlin

PD Dr Christian Voigt

Head of the Department of Evolutionary Ecology

phone: +49 30 5168 511

email: voigt@izw-berlin.de

Dr Gábor-Árpád Czirják

Scientist in the Department of Wildlife Diseases

phone: +49 30 5168214

email: czirjak@izw-berlin.de

Steven Seet

Science Communication

phone: +49 (0)30 5168125

email: seet@izw-berlin.de

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-03

To date, research in the field of combinatorial catalysts has relied on serendipitous discoveries of catalyst combinations. Now, scientists from Japan have streamlined a protocol that combines random sampling, high-throughput experimentation, and data science to identify synergistic combinations of catalysts. With this breakthrough, the researchers hope to remove the limits placed on research by relying on chance discoveries and have their new protocol used more often in catalyst informatics.

Catalysts, or their combinations, are compounds that significantly lower the energy required to drive chemical reactions to completion. In the field of "combinatorial catalyst design," the requirement of synergy--where one component ...

2021-02-03

Life changes influence the amount of physical activity in a person, according to a recent study by the University of Jyväskylä. The birth of children and a change of residence, marital status and place of work all influence the number of steps of men and women in different ways. For women, having children, getting a job and moving from town to the countryside reduce everyday exercise.

A study conducted by the Faculty of Sports & Health Sciences found that the birth of the first child significantly reduces the number of everyday steps in women. As children grow, women's aerobic steps, in turn, increase. Although the birth of children did not have a statistically significant effect on the number of steps in men, changes were also observed ...

2021-02-03

Use of waste heat contributes largely to sustainable energy supply. Scientists of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and T?hoku University in Japan have now come much closer to their goal of converting waste heat into electrical power at small temperature differences. As reported in Joule, electrical power per footprint of thermomagnetic generators based on Heusler alloy films has been increased by a factor of 3.4. (DOI: 10.1016/j.joule.2020.10.019)

Many technical processes only use part of the energy consumed. The remaining fraction leaves the system ...

2021-02-03

In the race to stop the spread of COVID-19, a three-layer cloth mask that fits well can effectively filter COVID particles, says a group of UBC researchers.

After testing several different mask styles and 41 types of fabrics, they found that a mask consisting of two layers of low-thread-count quilting cotton plus a three-ply dried baby wipe filter was as effective as a commercial non-surgical mask at stopping particles--and almost as breathable.

The cloth masks filtered out up to 80 per cent of 3-micron particles, and more than 90 per cent of 10-micron particles.

"We focused on particles larger than one micron because these are likely most important to COVID-19 transmission," explains researcher Dr. Steven Rogak, a professor of mechanical engineering who ...

2021-02-03

The genus Ficus (figs) and their agaonid pollinating fig wasps are a classic example of coevolution. It represents perhaps the most extreme and ancient (about 75 million years) obligate pollination mutualism known.

Previous studies have suggested that pollinator host-switching and hybridization existed in some fig taxa with genetic evidence based on relatively few genes. However, those cases were mainly treated as rare exceptions, and strict-sense coevolution was still treated as the dominate coevolution model for the codiversification of this "extreme" obligate pollination system with high species richness.

Together with colleagues from 11 institutions from home and abroad, researchers from the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical ...

2021-02-03

Scientists at Scripps Research have clarified the workings of a mysterious protein called Gαo, which is one of the most abundant proteins in the brain and, when mutated, causes severe movement disorders.

The findings, which appear in Cell Reports, are an advance in the basic understanding of how the brain controls muscles and could lead to treatments for children born with Gαo-mutation movement disorders. Such conditions--known as GNAO1-related neurodevelopmental disorders--were discovered only in the past decade, and are thought to affect at least hundreds of children around the world. Children with the disease suffer from severe developmental ...

2021-02-03

World-first 3D printed oesophageal stents developed by the University of South Australia could revolutionise the delivery of chemotherapy drugs to provide more accurate, effective and personalised treatment for patients with oesophageal cancer.

Fabricated from polyurethane filament and incorporating the chemotherapy drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), the new oesophageal stents are the first to contain active pharmaceutical ingredients within their matrix .

Their unique composition allows them to deliver up to 110 days of a sustained anti-cancer medication directly to the cancer site, restricting further tumour growth.

Importantly, the capabilities of 3D printing enabling rapid creation of individually tailored stents with patient-specific geometries and drug dosages.

PhD ...

2021-02-03

The COVID-19 pandemic is a great example of the importance of access to the Internet and to digital health information. Unfortunately, historical disparities in health care appear to be reflected in computer ownership, access to the Internet and use of digital health information. However, few studies have qualitatively explored reasons for digital health information disparity, especially in older adults.

A study led by Florida Atlantic University's Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing in collaboration with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the University of Massachusetts Medical ...

2021-02-03

A 30-year high in East African rainfall during 2018 and 2019 resulted in rising water levels and widespread flooding. The new study shows that emissions of methane - the second most important greenhouse gas - from flooded East African wetlands were substantially larger following these extreme rainfall events.

The study, led by Dr Mark Lunt from the University of Edinburgh's School of GeoSciences, used data from two different satellites in combination with an atmospheric model to evaluate methane emissions from East Africa. This included data from the European TROPOMI satellite instrument, launched in 2017, which provides information about atmospheric methane at ...

2021-02-03

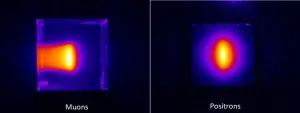

A new technique has taken the first images of muon particle beams. Nagoya University scientists designed the imaging technique with colleagues in Osaka University and KEK, Japan and describe it in the journal Scientific Reports. They plan to use it to assess the quality of these beams, which are being used more and more in advanced imaging applications.

Muons are charged particles that are 207 times the mass of electrons. They naturally form when cosmic rays strike atoms in the upper atmosphere, showering down onto every part of Earth's surface. They can penetrate through hundreds of meters of solids before being absorbed.

Scientists have used naturally ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] European hibernating bats cope with white-nose syndrome which kills North American bats