(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Feb. 3, 2020 - In a recurring pattern of evolution, SARS-CoV-2 evades immune responses by selectively deleting small bits of its genetic sequence, according to new research from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Since these deletions happen in a part of the sequence that encodes for the shape of the spike protein, the formerly neutralizing antibody can't grab hold of the virus, the researchers report today in Science. And because the molecular "proofreader" that usually catches errors during SARS-CoV-2 replication is "blind" to fixing deletions, they become cemented into the variant's genetic material.

"You can't fix what's not there," said study senior author Paul Duprex, Ph.D., director of the Center for Vaccine Research at the University of Pittsburgh. "Once it's gone, it's gone, and if it's gone in an important part of the virus that the antibody 'sees,' then it's gone for good."

Ever since the paper was first submitted as a preprint in November, the researchers watched this pattern play out, as several variants of concern rapidly spread across the globe. The variants first identified in the United Kingdom and South Africa have these sequence deletions.

Duprex's group first came across these neutralization-resistant deletions in a sample from an immunocompromised patient, who was infected with SARS-CoV-2 for 74 days before ultimately dying from COVID-19. That's a long time for the virus and immune system to play "cat and mouse," and gives ample opportunity to initiate the coevolutionary dance that results in these worrisome mutations in the viral genome that are occurring all over the world.

Then, Duprex enlisted the help of lead author Kevin McCarthy, Ph.D., assistant professor of molecular biology and molecular genetics at Pitt and an expert on influenza virus--a master of immune evasion--to see whether the deletions present in the viral sequences of this one patient might be part of a larger trend.

McCarthy and colleagues pored through the database of SARS-CoV-2 sequences collected across the world since the virus first spilled over into humans.

When the project started, in the summer of 2020, SARS-CoV-2 was thought to be relatively stable, but the more McCarthy scrutinized the database, the more deletions he saw, and a pattern emerged. The deletions kept happening in the same spots in the sequence, spots where the virus can tolerate a change in shape without losing its ability to invade cells and make copies of itself.

"Evolution was repeating itself," said McCarthy, who recently started up a structural virology lab at Pitt's Center for Vaccine Research. "By looking at this pattern, we could forecast. If it happened a few times, it was likely to happen again."

Among the sequences McCarthy identified as having these deletions was the so-called "U.K. variant"--or to use its proper name, B.1.1.7. By this point, it was October 2020, and B.1.1.7 hadn't taken off yet. In fact, it didn't even have a name, but it was there in the datasets. The strain was still emerging, and no one knew then the significance that it would come to have. But McCarthy's analysis caught it in advance by looking for patterns in the genetic sequence.

Reassuringly, the strain identified in this Pittsburgh patient is still susceptible to neutralization by the swarm of antibodies present in convalescent plasma, demonstrating that mutational escape isn't all or nothing. And that's important to realize when it comes to designing tools to combat the virus.

"Going after the virus in multiple different ways is how we beat the shapeshifter," Duprex said. "Combinations of different antibodies, combinations of nanobodies with antibodies, different types of vaccines. If there's a crisis, we'll want to have those backups."

Although this paper shows how SARS-CoV-2 is likely to escape the existing vaccines and therapeutics, it's impossible to know at this point exactly when that might happen. Will the COVID-19 vaccines on the market today continue to offer a high level of protection for another six months? A year? Five years?

"How far these deletions erode protection is yet to be determined," McCarthy said. "At some point, we're going to have to start reformulating vaccines, or at least entertain that idea."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on the study include Linda Rennick, Ph.D., Sham Nambulli, Ph.D., of Pitt; Lindsey Robinson-McCarthy, Ph.D., formally Harvard Medical School and now working as a virologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center; and William Bain, M.D., and Ghady Haidar, M.D., of Pitt and UPMC.

Funding for this study was provided by the Richard King Mellon Foundation, Hillman Family Foundation and UPMC Immune Transplant and Therapy Center.

To read this release online or share it, visit https://www.upmc.com/media/news/020321-mccarthy-duprex-deletions.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Erin Hare

Mobile: 412-738-1097

E-mail: HareE@upmc.edu

Contact: Ana Gorelova

Mobile: 412-491-9411

E-mail: GorelovaA@upmc.edu

Researchers have identified a pattern of deletions in the spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 that can prevent antibody binding. Virus lineages featuring this mechanism are currently being transmitted between individuals globally, they say. Their results - reported after analyzing nearly 150,000 S gene sequences collected from many parts of the world - exhibit a form of virus "escape" that resulted from a common, strong selective pressure; for example, the authors identified at least nine instances where deletion variants arose in patients whose COVID-19 infections were persistent. So far, the strongest indicator of protection against SARS-CoV-2 appears to be humoral immunity, such as by antibodies, ...

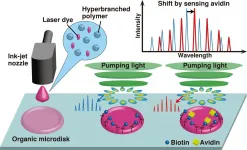

WASHINGTON -- Researchers have developed a unique inkjet printing method for fabricating tiny biocompatible polymer microdisk lasers for biosensing applications. The approach enables production of both the laser and sensor in a room temperature, open-air environment, potentially enabling new uses of biosensing technologies for health monitoring and disease diagnostics.

"The ability to use an inexpensive and portable commercial inkjet printer to fabricate a sensor in an ambient environment could make it possible to produce biosensors on-site as needed," said research team leader Hiroaki Yoshioka from Kyushu University in Japan. "This could help make biosensing widespread even in economically disadvantaged ...

Coffee rust is a parasitic fungus and a big problem for coffee growers around the world. A study in the birthplace of coffee - Ethiopia - shows that another fungus seems to have the capacity to supress the rust outbreaks in this landscape.

"Coffee leaf rust is a fungal disease that is a problem for coffee growers around the world, especially on Arabica coffee, which accounts for three quarters of global coffee production and has the finest cup quality. There is a need to learn more about natural solutions instead of just applying pesticides," says Kristoffer Hylander, professor at the Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences (DEEP) at Stockholm ...

Many nations place drugs into various schedules or categories according to their risk of being abused and their medical value. At times, drugs are rescheduled to a more restrictive category to reduce misuse by constricting supply. A new study examined lessons from past efforts worldwide to schedule and reschedule drugs to identify general patterns and found that rescheduling drugs can lower use as well as the dangers associated with the drug. The findings have implications for policy.

The study, by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), is published in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

"Our review suggests that rescheduling drugs can often disrupt trends in prescribing, use, or harms," says Jonathan Caulkins, professor of operations research and public policy at CMU's ...

In the first longitudinal study to follow Georgia pre-K students through middle school, Stacey Neuharth-Pritchett, associate dean for academic programs and professor in UGA's Mary Frances Early College of Education, found that participating in pre-K programs positively predicted mathematical achievement in students through seventh grade.

"Students who participated in the study were twice as likely to meet the state standards in their mathematics achievement," said Neuharth-Pritchett. "School becomes more challenging as one progresses through the grades, and so if ...

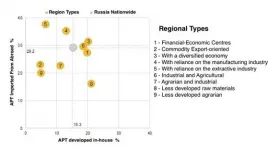

Russian enterprises have limited opportunities to carry out technological modernisation on their own. Their technological portfolios reveal a high dependence on imported solutions and a limited deployment of their own developments, HSE University researchers discovered.

In recent years, there has been a growing demand for the use of advanced manufacturing technologies (AMT) in Russia. Between 2011 and 2018, the number of AMT used increased by 33%, and in 2018 they amounted to almost 255,000 units in absolute terms. Meanwhile, innovation strategies focused on independent development of novel manufacturing solutions are not widespread in Russia. Fewer than ...

GROUND-BREAKING research from the University of Huddersfield, announced ahead of World Cancer Day 2021, proves that scalp cooling physically protects hair follicles from chemotherapy drugs. It is the world's first piece of biological evidence that explains how scalp cooling actually works and the mechanism behind its protection of the hair follicle.

The study, entitled 'Cooling-mediated protection from chemotherapy drug-induced cytotoxicity in human keratinocytes by inhibition of cellular drug uptake', has been published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE .

The data was part of an innovative hair follicle research project carried out by the dedicated Scalp Cooling ...

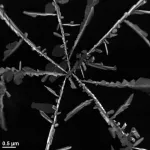

Antimicrobial packaging is being developed to extend the shelf life and safety of foods and beverages. However, there is concern about the transfer of potentially harmful materials, such as silver nanoparticles, from these types of containers to consumables. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces illustrate that silver embedded in an antimicrobial plastic can leave the material and form nanoparticles in foods and beverages, particularly in sweet and sugary ones.

Some polymers containing nanoparticles or nanocomposites can slow ...

In the Namib Desert in southwestern Africa, the Kuiseb River, an ephemeral river which is dry most of the year, plays a vital role to the region. It provides most of the vegetation to the area and serves as a home for the local indigenous people, and migration corridor for many animals. The overall vegetation cover increased by 33% between 1984 and 2019, according to a Dartmouth study published in Remote Sensing .

The study leveraged recent drone imagery and past satellite imagery to estimate past vegetation cover in this linear oasis of the Kuiseb River, a fertile area in the middle of one of the driest deserts ...

Some of the most commonly used drugs for treating hereditary breast and ovarian cancers may not work the way we thought they did, according to new University of Colorado Boulder research.

The paper, published February 2 in the journal Nature Communications, sheds new light on how they do work and could open the door to new next-generation medications that work better, the authors said.

"Despite the success of these drugs which sell in the billions of dollars per year and treat many thousands of patients, there are many unknowns about their potency and efficacy that if better understood ...