Study links brain cells to depression

New research linking major depression to a reduced number of cells in the brain that support neuron function, brings hope for targeted treatment options

2021-02-04

(Press-News.org) A new study further highlighting a potential physiological cause of clinical depression could guide future treatment options for this serious mental health disorder. Published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, researchers show differences between the cellular composition of the brain in depressed adults who died by suicide and non-psychiatric individuals who died suddenly by other means.

"We found a reduced number of astrocytes, highlighted by staining the protein vimentin, in many regions of the brain in depressed adults," reports Naguib Mechawar, a Professor at the Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Canada, and senior author of this article. "These star-shaped cells are important because they support the optimal function of brain neurons. Our findings confirm and extend previous research implicating astrocytes in the pathology of depression."

Major depressive disorder, also referred to as clinical depression, causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest, leading to a variety of serious emotional and physical problems. With approval from the Research Ethics Board, the team at the Douglas Institute (McGill University) used postmortem analysis to add weight to the theory that astrocytes play a role in this disorder.

Same shape different number

"We analyzed the astrocytes in the brain by staining specific proteins found in their structure -- vimentin and GFAP. Vimentin staining has not been used before in this context, but it provides a clear, complete and unprecedented view of the entire microscopic structure of these cells," explains Liam O'Leary, who completed this study at McGill University as part of his PhD research. "Using a microscope, we counted the number of astrocytes in cross sections of the brain, enabling us to estimate how many were in each region. We also analyzed the 3D structure of over three hundred individual astrocytes for any differences."

The postmortem analysis revealed that in depression, while the number of astrocytes differed, they have a similar structure to psychiatrically healthy individuals.

"This research indicates that depression may be linked to the cellular composition of the brain. The promising news is that unlike neurons, the adult human brain continually produces many new astrocytes. Finding ways that strengthen these natural brain functions may improve symptoms in depressed individuals," says Mechawar.

Target for treatment

"Our study provides a strong rationale for developing drugs that counteract the apparent loss of astrocytes in depression," says O'Leary. "No antidepressants have yet been developed to target these cells directly, although the leading theory for the rapid antidepressant action of ketamine, a relatively new treatment option, is that it corrects for astrocyte abnormality."

Future research hopes to address some limitations of the current study and to look deeper at the association of astrocytes with depression.

"While this study is the most comprehensive so far, it was only conducted with samples from male patients. We want to widen this study to investigate samples from female patients since it is now known that the neurobiology of depression differs quite significantly between men and women," says Mechawar, who also acknowledges the critical role of the donors and their families.

"Tissue donation to scientific research allows us to better understand the cellular and molecular dysfunctions underlying brain disorders, thereby supporting the development of better mental healthcare treatments."

If you or someone you know is affected by depression, please find help now. The International Association for Suicide Prevention provide a list of crisis centers across the world that can offer support in your region.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-04

Researchers from University of Notre Dame, York University (Canada), and University of New England (Australia) published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that identifies a novel reason why people under-save and demonstrates a simple, short, and inexpensive intervention that increases intentions to save and actual savings.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Popping the Positive Illusion of Financial Responsibility Can Increase Personal Savings: Applications in Emerging and Western Markets" and is authored by Emily Garbinsky, Nicole Mead, and Daniel Gregg.

People around the world are not saving enough money. Since increasing ...

2021-02-04

WASHINGTON--The start of California's annual rainy season has been pushed back from November to December, prolonging the state's increasingly destructive wildfire season by nearly a month, according to new research. The study cannot confirm the shift is connected to climate change, but the results are consistent with climate models that predict drier autumns for California in a warming climate, according to the authors.

Wildfires can occur at any time in California, but fires typically burn from May through October, when the state is in its dry season. The start of the rainy season, historically in November, ends wildfire season as plants become too moist to burn.

California's rainy season has been starting progressively later in recent decades and climate ...

2021-02-04

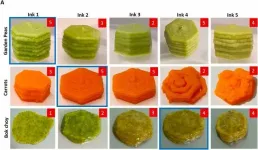

Researchers from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore), Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) have developed a new way to create "food inks" from fresh and frozen vegetables, that preserves their nutrition and flavour better than existing methods.

Food inks are usually made from pureed foods in liquid or semi-solid form, then 3D-printed by extrusion from a nozzle, and assembled layer by layer.

Pureed foods are usually served to patients suffering from swallowing difficulties known as dysphagia. To present the ...

2021-02-04

Politicians around the world must be held to account for mishandling the covid-19 pandemic, argues a senior editor at The BMJ today.

Executive editor, Dr Kamran Abbasi, argues that at the very least, covid-19 might be classified as 'social murder' that requires redress.

Today 'social murder' may describe a lack of political attention to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age that exacerbate the pandemic.

When politicians and experts say that they are willing to allow tens of thousands of premature deaths, for the sake of population immunity or in the hope of propping up the economy, is that not premeditated ...

2021-02-03

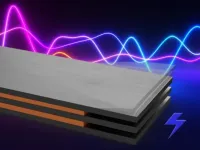

Piezoelectric materials hold great promise as sensors and as energy harvesters but are normally much less effective at high temperatures, limiting their use in environments such as engines or space exploration. However, a new piezoelectric device developed by a team of researchers from Penn State and QorTek remains highly effective at elevated temperatures.

Clive Randall, director of Penn State's Materials Research Institute (MRI), developed the material and device in partnership with researchers from QorTek, a State College, Pennsylvania-based company specializing in smart material devices and high-density power electronics.

"NASA's need ...

2021-02-03

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Muscle wasting, or the loss of muscle tissue, is a common problem for people with cancer, but the precise mechanisms have long eluded doctors and scientists. Now, a new study led by Penn State researchers gives new clues to how muscle wasting happens on a cellular level.

Using a mouse model of ovarian cancer, the researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes -- particles in the cell that make proteins. Because muscle mass is mainly determined by protein synthesis, having less ribosomes likely explains why muscles waste away in cancer.

Gustavo Nader, associate professor of kinesiology and physiology at Penn State, said the findings suggest a mechanism for muscle wasting that could be relevant ...

2021-02-03

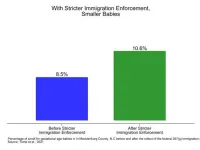

DURHAM, N.C. -- Harsher immigration law enforcement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement leads to decreased use of prenatal care for immigrant mothers and declines in birth weight, according to new Duke University research.

In the study, published in PLOS ONE, researchers examine the effects of the federal 287(g) immigration program after it was introduced in North Carolina in 2006. Under 287(g) programs, which are still in effect, local law officers are deputized to act as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, with authority to question individuals about immigration status, detain them, and if necessary, begin deportation proceedings.

According to the study findings, the 2006 policy change reduced birth weight ...

2021-02-03

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Hypoxia -- where a tissue is deprived of an adequate supply of oxygen -- is a feature inside solid cancer tumors that renders them highly invasive and resistant to treatment. Study of how cells adapt to this critical stressor, by altering their metabolism to survive in a low-oxygen environment, is important to better understand tumor growth and spread.

Researchers led by Rajeev Samant, Ph.D., professor of pathology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, now report that chronic hypoxia, surprisingly, upregulates RNA polymerase I activity and alters the methylation patterns on ribosomal RNAs. These altered epigenetic marks on the ribosomal RNAs appear to create a pool of specialized ribosomes that can differentially ...

2021-02-03

As a native animal, kangaroos aren't typically considered a threat to Australian vegetation.

While seen as a pest on farmland - for example, when competing with livestock for resources - they usually aren't widely seen as a pest in conservation areas.

But a new collaborative study led by UNSW Sydney found that conservation reserves are showing signs of kangaroo overgrazing - that is, intensive grazing that negatively impacts the health and biodiversity of the land.

Surprisingly, the kangaroos' grazing impacts appeared to be more damaging to the land than rabbits, an introduced species.

"The kangaroos had severe impacts on soils and vegetation that were symptomatic of overgrazing," says Professor Michael Letnic, senior author of the paper and ...

2021-02-03

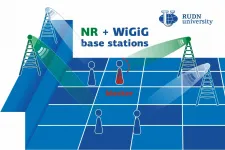

Mathematicians from RUDN University suggested and tested a new method to assess the productivity of fifth-generation (5G) base stations. The new technology would help get rid of mobile access stations and even out traffic fluctuations. The results of the study were published in the IEEE Conference Publication.

Stations of the new 5G New Radio (NR) communication standard developed by the 3GPP consortium are expected to shortly be installed in large quantities all over the world. First of all, the stations will be deployed in places with high traffic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study links brain cells to depression

New research linking major depression to a reduced number of cells in the brain that support neuron function, brings hope for targeted treatment options