(Press-News.org) The lung is a complex organ whose main function is to exchange gases. It is the largest organ in the human body and plays a key role in the oxygenation of all the organs. Due to its structure, cellular composition and dynamic microenvironment, is difficult to mimic in vitro.

A specialized laboratory of the ARTORG Center for Biomedical Engineering Research, University of Bern, headed by Olivier Guenat has developed a new generation of in-vitro models called organs-on-chip for over 10 years, focusing on modeling the lung and its diseases. After a first successful lung-on-chip system exhibiting essential features of the lung, the Organs-on-Chip (OOC) Technologies laboratory has now developed a purely biological next-generation lung-on-chip in collaboration with the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Germany and the Thoracic Surgery and Pneumology Departments at Inselspital.

A fully biodegradable life-sized air-blood-barrier

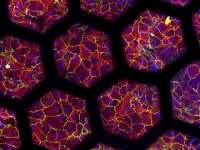

Pauline Zamprogno, who developed the new model for her PhD thesis at the OOC, summarizes its characteristics: "The new lung-on-chip reproduces an array of alveoli with in vivo like dimensions. It is based on a thin, stretchable membrane, made with molecules naturally found in the lung: collagen and elastin. The membrane is stable, can be cultured on both sides for weeks, is biodegradable and its elastic properties allow mimicking respiratory motions by mechanically stretching the cells."

By contrast to the first generation, which was also built by the team around Olivier Guenat, the developed system reproduces key aspects of the lung extracellular matrix (ECM): Its composition (cells support made of ECM proteins), its structure (array of alveoli with dimension similar to those found in vivo + fiber structure) and its properties (biodegradability, a key aspect to investigating barrier remodeling during lung diseases such as IPF or COPD). Additionally, the fabrication process is simple and less cumbersome than that of a polydimethylsiloxane stretchable porous membrane from the first-generation lung-on-chip.

Broad potential clinical applications

Cells to be cultured on the new chip for research are currently obtained from cancer patients undergoing lung resections at the Inselspital Department of Thoracic Surgery. Department Head Ralph Schmid sees a double advantage in the system: "The second generation lung-on-chip can be seeded with either healthy or diseased lung alveolar cells. This provides clinicians with both a better understanding of the lung's physiology and a predictive tool for drug screening and potentially also for precision medicine, identifying the specific therapy with the best potential of helping a particular patient."

"The applications for such membranes are broad, from basic science investigations into lung functionalities and pathologies, to identifying new pathways, and to a more efficient discovery of potential new therapies", says Thomas Geiser, Head of the Department of Pneumology at the Inselspital and Director of Teaching and Research of the Insel Gruppe.

Powerful alternative to animal models in research

As an additional plus, the new lung-on-chip can reduce the need for pneumological research based on animal models. "Many promising drug candidates successfully tested in preclinical models on rodents have failed when tested in humans due to differences between the species and in the expression of a lung disease," explains Olivier Guenat. "This is why, in the long term, we aim to reduce animal testing and provide more patient-relevant systems for drug screening with the possibility of tailoring models to specific patients (by seeding organs-on-chip with their own cells)."

The new biological lung-on-chip will be further developed by Pauline Zamprogno and her colleagues from the OOC Technologies group to mimic a lung with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a chronic disease of the lung leading to progressive scarring of the lung tissue within the framework of a research project funded by the Swiss 3R Competence Center (3RCC). "My new project consists in the development of an IPF-on- chip model based on the biological membrane. So far, we have develop a healthy air-blood barrier. Now it's time to use it to investigate a real biological question," says Zamprogno.

Research group Organs-On-Chip Technologies of the ARTORG Center

This specialized group of the ARTORG Center for Biomedical Engineering Research develops organs-on-chip, focusing on the lung and its diseases, in collaboration with the Departments of Pulmonary Medicine and Thoracic Surgery of the Inselspital. The group combines engineering, in particular microfluidics and microfabrication, cell biology and tissue engineering methods, material sciences and medicine.

Their first development of a breathing lung-on-chip is further developed in collaboration with the start-up AlevoliX, with the aim to revolutionize preclinical research. Recently the group has developed an entirely biological second-generation lung-on-chip focusing on recreating the air-blood barrier of the lung. A second research direction aims at developing a functional lung microvasculature. Here, lung endothelial cells are seeded in a micro-engineered environment, where they self-assemble to build a network of perfusable and contractile microvessels of only a few tens of micrometers in diameter.

Next to pharmaceutical applications, organs-on-chip are seen as having the potential to be used in precision medicine to test the patient's own cells in order to tailor the best therapy. Furthermore, such systems have the significant potential to reduce animal testing in medical and life-science research. The OOC group operates the Organs-on-Chip Facility, providing scientists from the University of Bern, the University Hospital of Bern and beyond an infrastructure and equipment to produce microfluidic devices and test organs-on-chips.

INFORMATION:

A video about the second-generation lung-on-chip can be found here:

https://youtu.be/s6bTzRmWr9w

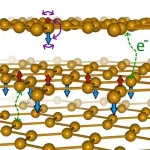

Researchers have identified a new form of magnetism in so-called magnetic graphene, which could point the way toward understanding superconductivity in this unusual type of material.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, were able to control the conductivity and magnetism of iron thiophosphate (FePS3), a two-dimensional material which undergoes a transition from an insulator to a metal when compressed. This class of magnetic materials offers new routes to understanding the physics of new magnetic states and superconductivity.

Using new high-pressure techniques, the researchers have shown what happens to magnetic graphene during the transition from insulator to conductor and into ...

A Rochester Institute of Technology researcher has validated a tool measuring adherence to a popular child feeding approach used by pediatricians, nutritionists, social workers and child psychologists to assess parents' feeding practices and prevent feeding problems.

The best-practice approach, known as the Satter Division of Responsibility in Feeding, has now been rigorously tested and peer reviewed, resulting in the quantifiable tool sDOR.2-6y. The questionnaire will become a standard parent survey for professionals and researchers working in the early childhood development field, predicts lead researcher ...

Astronomers may have found our galaxy's first example of an unusual kind of stellar explosion. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, adds to the understanding of how some stars shatter and seed the universe with elements critical for life on Earth.

This intriguing object, located near the center of the Milky Way, is a supernova remnant called Sagittarius A East, or Sgr A East for short. Based on Chandra data, astronomers previously classified the object as the remains of a massive star that exploded as a supernova, one of many kinds of exploded stars that scientists have catalogued.

Using longer Chandra observations, a team of astronomers has now instead concluded that the object is left over from a different type of ...

Findings from a new study on Alzheimer's disease (AD), led by researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), could eventually help clinicians identify people at highest risk for developing the irreversible, progressive brain disorder and pave the way for treatments that slow or prevent its onset.

The research, published in the journal Scientific Reports in early January, has demonstrated that a shorter form of the protein peptide believed responsible for causing AD (beta-amyloid 42, or Aβ42) halts the damage-causing mechanism of ...

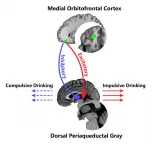

A pathway in the brain where alcohol addiction first develops has been identified by a team of British and Chinese researchers in a new study

Could lead to more effective interventions when tackling compulsive and impulsive drinking

More than 3 million deaths every year are related to alcohol use globally, according to the World Health Organisation

The physical origin of alcohol addiction has been located in a network of the human brain that regulates our response to danger, according to a team of British and Chinese researchers, co-led by the University of Warwick, the University ...

On a brisk November morning in 2018, a fire sparked in a remote stretch of canyon in Butte County, California, a region nestled against the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Fueled by a sea of tinder created by drought, and propelled by powerful gusts, the flames grew and traveled rapidly. In less than 24 hours, the fire had swept through the town of Paradise and other communities, leaving a charred ruin in its wake.

The Camp Fire was the costliest disaster worldwide in 2018 and, having caused 85 deaths and destroyed more than 18,000 buildings, it became both the deadliest and most destructive wildfire ...

An unusual biologically active porphyrin compound was isolated from seabed dweller Ophiura sarsii. The substance might be used as an affordable light-sensitive drug for innovative photodynamic therapy and for targeted treatment of triple-negative breast cancer and some other cancers. Researchers from the School of Biomedicine of Far Eastern Federal University (FEFU) and the University of Geneva reported the findings in Marine Drugs.

The seabed dweller Ophiura sarsii, the source of the new compound, was isolated at a depth of 15-18 meters in Bogdanovich Bay, Russky Island (Vladivostok, Russia). Ophiuras may resemble ...

DALLAS - Feb. 8, 2021 - Pregnant women, who are at increased risk of preterm birth or pregnancy loss if they develop a severe case of COVID-19, need the best possible guidance on whether they should receive a COVID-19 vaccine, according to an article by two UT Southwestern obstetricians published today in JAMA. That guidance can take lessons from what is already known about other vaccines given during pregnancy.

In the Viewpoint article, Emily H. Adhikari, M.D., and Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., describe how the available safety and effectiveness data, basic science of mRNA vaccines, and long history ...

DALLAS - Feb. 8, 2021 - A new nanoparticle-based drug can boost the body's innate immune system and make it more effective at fighting off tumors, researchers at UT Southwestern have shown. Their study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is the first to successfully target the immune molecule STING with nanoparticles about one millionth the size of a soccer ball that can switch on/off immune activity in response to their physiological environment.

"Activating STING by these nanoparticles is like exerting perpetual pressure on the accelerator to ramp up the natural innate immune response to a tumor," says study leader Jinming Gao, Ph.D., a professor in UT Southwestern's Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive ...

AURORA, Colo. (February 8, 2021) - Researchers from the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have found that immune responses to insulin could help identify individuals most at risk for developing Type 1 diabetes.

The study, out recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, measured immune responses from individuals genetically predisposed to developing Type 1 diabetes (T1D) to naturally occurring insulin and hybrid insulin peptides. Since not all genetically predisposed individuals ...