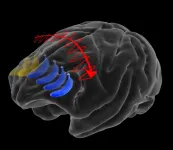

(Press-News.org) Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep continuous track of what's important to us, even though our visual system's basic wiring requires mapping what we see on our left in the right side of our brain and what we see on our right in the left side of the brain.

"You need to know where things are in the real world, regardless of where you happen to be looking or how you are oriented at a given moment," said study lead author Scott Brincat, a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Picower Professor Earl Miller, the senior author. "But the representation that your brain gets from the outside world changes every time you move your eyes around."

In their experiments, Brincat, Miller and co-authors found that when an object switches sides in the field of view, the brain rapidly employs a telltale change in the synchrony of brain wave frequencies to shepherd the memory information from one side of the brain to the other. The transfer, which occurs in mere milliseconds, recruits a new group of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of the opposite brain hemisphere to store the memory. This new ensemble of neurons encodes the object based on its new position, but the brain continues to recognize it as the object that used to be in the other hemisphere's field of view.

That ability--to remember that something is the same thing no matter how it's moving around relative to our eyes--is what gives us the freedom to control where we look, Miller said. A quarterback can decide to shift his gaze from the left side of the field to the right side without having to fear that he'll instantly forget that those left-side receivers are still there, even if changing the gaze position has substantially shifted them within, or even out of, his field of view.

"If you didn't have that, we would just be simple creatures who could only react to whatever is coming right at us in the environment, that's all," Miller said. "But because we can hold things in mind, we can have volitional control over what we do. We don't have to react to something now, we can save it for later."

Shifting sides

In the lab, the researchers measured the activity of hundreds of neurons in the prefrontal cortex of both brain hemispheres as animals played a game. They had to fix their gaze on one side of a screen as an image of an object (e.g. a banana) appeared briefly in the middle of the screen. The object thus appeared on one or the other side of their field of view, and due to the brain's crossed wiring, it was processed in the opposite cortical hemisphere. The animal had to hold the image in mind, then indicate if a subsequently presented image was of a different object (e.g. an apple). On some trials, though, while the original object was held in working memory the animals were cued to switch their gaze from one side to the other, effectively changing which side of their field of view the remembered image was on.

Animals were accurate in remembering whether the images they were presented matched, but their performance suffered just a little bit in cases where they had to shift their gaze. Brincat said the error suggests that having to keep up with the shift is not as easy for the brain as it seems.

"It feels trivial to us, but it apparently isn't," he said.

To analyze their measurements in the brain, the team trained a computer program called a decoder to identify patterns in the raw data of neural activity that indicated the memory of the object image. As expected, that analysis showed that the brain encoded information about each image in the hemisphere opposite of where it was in the field of view. But more remarkably, it also showed that in cases where the animals shifted their gaze across the screen, neural activity encoding the memory information shifted from one brain hemisphere to the other.

The team also measured the overall rhythms of the neurons' collective activity, or brain waves. They found that the transfer of a memory from one hemisphere to the other consistently occurred with a signature change in those rhythms. As the transfer occurred, the synchrony across hemispheres of very low frequency "theta" waves (~4-10 Hz) and high frequency "beta" waves (~17-40 Hz) rose and the synchrony of "alpha/beta" waves (~11-17 Hz) declined.

This push-and-pull pattern of rhythms closely resembles one that Miller's lab has found in many studies of how the cortex employs rhythms to transmit information. Increases in the combination of very low and higher frequency rhythms allows sensory information (i.e. representations of what the animal just saw) to be encoded or recalled. A power increase in the alpha/beta frequency range inhibits that encoding, acting as a sort of gate on sensory information processing.

"This is another form of gating," Miller said. "This time alpha/beta is gating the memory transfer between hemispheres."

Spotting a surprise

While the rhythm patterns seemed consistent with prior studies, the researchers were surprised by another finding of the study: Given the same object image in the same spot in the field of view, the prefrontal cortex employed different neurons if it was initially seen at that location vs. transferred from the other hemisphere. In other words, animals seeing a banana in the left side of their vision recruited a different neural ensemble to represent that memory than they did if the banana was previously seen on the right and then transferred to that spot.

To Miller, the finding has an intriguing implication. Neuroscientists once thought that individual neurons were the basic unit of function in the brain and more recently have begun to think that instead ensembles of neurons are. The new findings, however, suggest that even the same information could still be encoded by different, arbitrarily assembled ensembles.

"Perhaps even ensembles aren't the functional units of the brain," Miller speculated. "So what is the functional unit of the brain? It's the computational space that brain network activity creates."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Brincat and Miller the paper's other authors are Jacob Donoghue, Meredith Mahnke, Simon Kornblith and Mikael Lundqvist.

The National Institute of Mental Health, Office of Naval Research, the JPB Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded the research.

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...

What The Study Did: The National Health Service in Italy provides universal coverage to citizens but because no approved drug was available for COVID-19, patients received potentially effective drugs, participated in clinical trials, accessed compassionate drug use programs or self-medicated. This study evaluated changes in drug demand during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy compared with the period before the outbreak.

Authors: Adriana Ammassari, M.D., of the Italian Medicines Agency in Rome, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37060)

Editor's ...

Philadelphia, February 8, 2021--Adding to a growing body of research affirming the benefits of fetal surgery for spina bifida, new findings show prenatal repair of the spinal column confers physical gains that extend into childhood. The researchers found that children who had undergone fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, were more likely than those who received postnatal repair to walk independently, go up and down stairs, and perform self-care tasks like using a fork, washing hands and brushing teeth. They also had stronger leg muscles and walked faster than children who had their spina bifida surgery ...

What The Study Did: This observational study compared different measures of prediabetes and the risk of progression to diabetes among adults age 71 to 90.

Authors: Mary R. Rooney, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed what percentage of the Virginia population had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 after the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the U.S.

Authors: Eric R. Houpt, M.D., of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35234)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for ...

If temperature varies strongly from day to day, the economy grows less. Through these seemingly small variations climate change may have strong effects on economic growth. This shows data analyzed by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Columbia University and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC). In a new study in Nature Climate Change, they juxtapose observed daily temperature changes with economic data from more than 1,500 regions worldwide over 40 years - with startling results.

"We ...

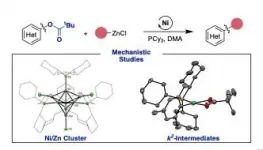

Negishi cross-coupling reactions have been widely used to form C-C bonds since the 1970s and are often perceived as the result of two metals (i.e zinc and palladium/nickel) working in synergy. But like all relationships, there is more under the surface than what we first expected. PhD student Craig Day and Dr. Rosie Somerville from the Martin group at ICIQ have delved into the Negishi cross-coupling of aryl esters using nickel catalysis to understand how this reaction works at the molecular level and how to improve it. The results have been published in Nature Catalysis.

Compared to palladium, nickel has the advantage of being readily available transition metal, ...

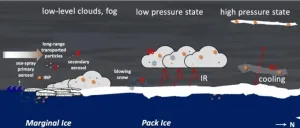

It's clear that rising greenhouse gas emissions are the main driver of global warming. But on a regional level, several other factors are at play. That's especially true in the Arctic - a massive oceanic region around the North Pole which is warming two to three times faster than the rest of the planet. One consequence of the melting of the Arctic ice cap is a reduction in albedo, which is the capacity of surfaces to reflect a certain amount of solar radiation. Earth's bright surfaces like glaciers, snow and clouds have a high reflectivity. As snow and ice decrease, albedo decreases and more radiation is absorbed by the Earth, leading to a rise in ...

What The Study Did: Researchers investigated the association between the use of proton pump inhibitors among children and adolescents in Sweden and the risk of asthma.

Authors: Yun-Han Wang, M.Sc., B.Pharm., of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5710)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

What The Article Says: In this essay, the authors describe a 97-year-old patient who learned to titrate condensed chicken soup like a medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Yuenting Diana Kwong, M.D., M.A.S., University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8897)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...