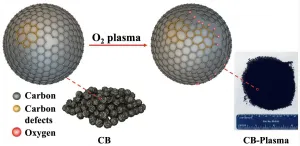

Rice scientists treated metal-free carbon black, the inexpensive, powdered product of petroleum production, with oxygen plasma. The process introduces defects and oxygen-containing groups into the structure of the carbon particles, exposing more surface area for interactions.

When used as a catalyst, the defective particles known as CB-Plasma reduce oxygen to hydrogen peroxide with 100% Faradaic efficiency, a measure of charge transfer in electrochemical reactions. The process shows promise to replace the complex anthraquinone-based production method that requires expensive catalysts and generates toxic organic byproducts and large amounts of wastewater, according to the researchers.

The research by Rice chemist James Tour and materials theorist Boris Yakobson appears in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Catalysis.

Hydrogen peroxide is widely used as a disinfectant, as well as in wastewater treatment, in the paper and pulp industries and for chemical oxidation. Tour expects the new process will influence the design of hydrogen peroxide catalysts going forward.

"The electrochemical process outlined here needs no metal catalysts, and this will lower the cost and make the entire process far simpler," Tour said. "Proper engineering of carbon structure could provide suitable active sites that reduce oxygen molecules while maintaining the O-O bond, so that hydrogen peroxide is the only product. Besides that, the metal-free design helps prevent the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide."

Plasma processing creates defects in carbon black particles that appear as five- or seven-member rings in the material's atomic lattice. The process sometimes removes enough atoms to create vacancies in the lattice.

The catalyst works by pulling two electrons from oxygen, allowing it to combine with two hydrogen electrons to create hydrogen peroxide. (Reducing oxygen by four electrons, a process used in fuel cells, produces water as a byproduct.)

"The selectivity towards peroxide rather than water originates not from carbon black per se but, as (co-lead author and Rice graduate student) Qin-Kun Li's calculations show, from the specific defects created by plasma processing," Yakobson said. "These catalytic defect sites favor the bonding of key intermediates for peroxide formation, lowering the reaction barrier and accelerating the desirable outcome."

Tour's lab also treated carbon black with ultraviolet-ozone and treated CB-Plasma after oxygen reduction with argon to remove most of the oxygen-containing groups. CB-UV was no better at catalysis than plain carbon black, but CB-Argon performed just as well as CB-Plasma with an even wider range of electrochemical potential, the lab reported.

Because the exposure of CB-Plasma to argon under high temperature removed most of the oxygen groups, the lab inferred the carbon defects themselves were responsible for the catalytic reduction to hydrogen peroxide.

The simplicity of the process could allow more local generation of the valuable chemical, reducing the need to transport it from centralized plants. Tour noted CB-Plasma matches the efficiency of state-of-the-art materials now used to generate hydrogen peroxide.

"Scaling this process is much easier than present methods, and it is so simple that even small units could be used to generate hydrogen peroxide at the sites of need," Tour said.

The process is the second introduced by Rice in recent months to make the manufacture of hydrogen peroxide more efficient. Rice chemical and biomolecular engineer Haotian Wang and his lab developed an oxidized carbon nanoparticle-based catalyst that produces the chemical from sunlight, air and water.

INFORMATION:

Rice graduate student Zhe Wang is co-lead author of the paper. Co-authors are Rice alumnus Chenhao Zhang, graduate students Zhihua Cheng, Weiyin Chen and Emily McHugh and undergraduate Robert Carter. Tour is the T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry as well as a professor of computer science and of materials science and nanoengineering. Yakobson is the Karl F. Hasselmann Professor of Materials Science and NanoEngineering and a professor of chemistry.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Office of Naval Research supported the research.

Read the abstract at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.0c04735.

This news release can be found online at https://news.rice.edu/2021/02/09/defective-carbon-simplifies-hydrogen-peroxide-production/

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Tour Group: https://www.jmtour.com

Yakobson Research Group: http://biygroup.blogs.rice.edu

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: https://naturalsciences.rice.edu

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https://engineering.rice.edu

Images for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/01/0201_PEROXIDE-1-WEB.jpg

Scientists at Rice University have introduced plasma-treated carbon black as a simple and highly efficient catalyst for the production of hydrogen peroxide. Defects created in the carbon provide more catalytic sites to reduce oxygen to hydrogen peroxide. (Credit: Tour Group/Yakobson Research Group/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/01/0201_PEROXIDE-2-WEB.jpg

Rice University scientists have revealed a new catalyst, plasma-treated carbon black, to reduce oxygen to valuable hydrogen peroxide. The process introduces defects to the carbon material's atomic honeycomb, providing more surface area for reactions. (Credit: Tour Group/Yakobson Research Group/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/01/0201_PEROXIDE-3-WEB.jpg

A transmission electron microscope image shows details of carbon black particles after treatment with plasma. Defects in the carbon lattice caused by the oxygen plasma enhance the material's ability to catalyze the production of hydrogen peroxide, according to Rice University scientists. (Credit: Tour Group/Yakobson Research Group/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,978 undergraduates and 3,192 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

Jeff Falk

713-348-6775

jfalk@rice.edu

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu