(Press-News.org) BOSTON - How often a person takes daytime naps, if at all, is partly regulated by their genes, according to new research led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and published in Nature Communications. In this study, the largest of its kind ever conducted, the MGH team collaborated with colleagues at the University of Murcia in Spain and several other institutions to identify dozens of gene regions that govern the tendency to take naps during the day. They also uncovered preliminary evidence linking napping habits to cardiometabolic health.

"Napping is somewhat controversial," says Hassan Saeed Dashti, PhD, RD, of the MGH Center for Genomic Medicine, co-lead author of the report with Iyas Daghlas, a medical student at Harvard Medical School (HMS). Dashti notes that some countries where daytime naps have long been part of the culture (such as Spain) now discourage the habit. Meanwhile, some companies in the United States now promote napping as a way to boost productivity. "It was important to try to disentangle the biological pathways that contribute to why we nap," says Dashti.

Previously, co-senior author Richa Saxena, PhD, principal investigator at the Saxena Lab at MGH, and her colleagues used massive databases of genetic and lifestyle information to study other aspects of sleep. Notably, the team has identified genes associated with sleep duration, insomnia, and the tendency to be an early riser or "night owl." To gain a better understanding of the genetics of napping, Saxena's team and co-senior author Marta Garaulet, PhD, of the department of Physiology at the University of Murcia, performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS), which involves rapid scanning of complete sets of DNA, or genomes, of a large number of people. The goal of a GWAS is to identify genetic variations that are associated with a specific disease or, in this case, habit.

For this study, the MGH researchers and their colleagues used data from the UK Biobank, which includes genetic information from 452,633 people. All participants were asked whether they nap during the day "never/rarely," "sometimes" or "usually." The GWAS identified 123 regions in the human genome that are associated with daytime napping. A subset of participants wore activity monitors called accelerometers, which provide data about daytime sedentary behavior, which can be an indicator of napping. This objective data indicated that the self-reports about napping were accurate. "That gave an extra layer of confidence that what we found is real and not an artifact," says Dashti.

Several other features of the study bolster its results. For example, the researchers independently replicated their findings in an analysis of the genomes of 541,333 people collected by 23andMe, the consumer genetic-testing company. Also, a significant number of the genes near or at regions identified by the GWAS are already known to play a role in sleep. One example is KSR2, a gene that the MGH team and collaborators had previously found plays a role in sleep regulation.

Digging deeper into the data, the team identified at least three potential mechanisms that promote napping:

Sleep propensity: Some people need more shut-eye than others.

Disrupted sleep: A daytime nap can help make up for poor quality slumber the night before.

Early morning awakening: People who rise early may "catch up" on sleep with a nap.

"This tells us that daytime napping is biologically driven and not just an environmental or behavioral choice," says Dashti. Some of these subtypes were linked to cardiometabolic health concerns, such as large waist circumference and elevated blood pressure, though more research on those associations is needed. "Future work may help to develop personalized recommendations for siesta," says Garaulet.

Furthermore, several gene variants linked to napping were already associated with signaling by a neuropeptide called orexin, which plays a role in wakefulness. "This pathway is known to be involved in rare sleep disorders like narcolepsy, but our findings show that smaller perturbations in the pathway can explain why some people nap more than others," says Daghlas.

Saxena is the Phyllis and Jerome Lyle Rappaport MGH Research Scholar at the Center for Genomic Medicine and an associate professor of Anesthesia at HMS.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, MGH Research Scholar Fund, Spanish Government of Investigation, Development and Innovation, the Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia through the Seneca Foundation, Academy of Finland, Instrumentarium Science Foundation, Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, and Medical Research Council.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2020, Mass General was named #6 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

Alongside the effects of lifestyle, including physical exercise and diet, on ageing, research has increasingly turned its attention to the potential cognitive benefits of musical hobbies. However, such research has mainly concentrated on hobbies involving musical instruments.

The cognitive benefits of playing an instrument are already fairly well known: such activity can improve cognitive flexibility, or the ability to regulate and switch focus between different thought processes. However, the cognitive benefits of choir singing have so far been investigated very little.

Now, a study recently ...

BOSTON - When patients arrive in emergency departments and hospitals with symptoms consistent with COVID-19, it's critical to isolate them to avoid the potential spread of infection, but keeping patients isolated longer than needed could delay patient care, take up hospital beds needed for other patients, and unnecessarily use up personal protective equipment. A team led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) has now created a tool to guide frontline clinicians through diagnostic evaluations of such patients so that they'll know when it's safe to discontinue precautions. The tool was developed and validated in a study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

In the spring of 2020, due to the risk of false-negative ...

UPTON, NY--Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory, Stony Brook University (SBU), and other collaborating institutions have uncovered dynamic, atomic-level details of how an important platinum-based catalyst works in the water gas shift reaction. This reaction transforms carbon monoxide (CO) and water (H2O) into carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen gas (H2)--an important step in producing and purifying hydrogen for multiple applications, including use as a clean fuel in fuel-cell vehicles, and in the production of hydrocarbons.

But because ...

A team of Russian scientists from NUST MISIS, Tomsk Polytechnic University (TPU) and Boreskov Institute of Catalysis has suggested a new approach to modifying the combustion behavior of coal. The addition of copper salts reduces the content of unburnt carbon in ash residue by 3.1 times and CO content in the gaseous combustion products by 40%, the scientists found. The research was published in Fuel Processing Technology.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), coal is the predominant energy resource used as the primary fuel for power generation. According to reports, coal supplied over one-third of global electricity generation in ...

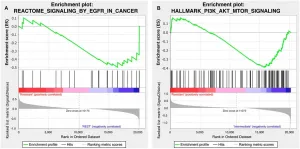

Oncotarget published "Combination of copanlisib with cetuximab improves tumor response in cetuximab-resistant patient-derived xenografts of head and neck cancer" which reported that HNSCC is frequently associated with either amplification or mutational changes in the PI3K pathway, making PI3K an attractive target, particularly in cetuximab-resistant tumors.

Here, the authors explored the antitumor activity of the selective, pan-class I PI3K inhibitor copanlisib with predominant activity towards PI3Kα and δ in monotherapy and in combination with cetuximab using a mouse clinical trial set-up with 33 patient-derived xenograft models with known HPV and PI3K mutational status and available data ...

Scientists and public health experts have long known that certain individuals, termed "super-spreaders," can transmit COVID-19 with incredible efficiency and devastating consequences.

Now, researchers at Tulane University, Harvard University, MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital have learned that obesity, age and COVID-19 infection correlate with a propensity to breathe out more respiratory droplets -- key spreaders of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Their findings were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Using data from an observational study of 194 healthy people and an experimental study of nonhuman primates with COVID-19, researchers found that exhaled aerosol particles vary greatly ...

(New York, NY) February 10, 2021 - A research team led by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (Icahn Mount Sinai) has built the first cellular model to depict the evolution of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), from its early to late stages. By using gene editing technologies to alter genes that make cells malignant, the team was able to identify potential therapeutic targets for early disease stages. The study was reported in the journal Cell Stem Cell in February.

The therapeutic targets could be applicable not just to AML but also to the blood cancer myelodysplastic syndrome and clonal hematopoiesis, which is often a preleukemic condition.

"We essentially built from scratch a model of leukemia that characterizes the ...

Global emissions of a potent substance notorious for depleting the Earth's ozone layer - the protective barrier which absorbs the Sun's harmful UV rays - have fallen rapidly and are now back on the decline, according to new research.

Two international studies published today in Nature, show emissions of CFC-11, one of the many chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) chemicals once widely used in refrigerators and insulating foams, are back on the decline less than two years after the exposure of their shock resurgence in the wake of suspected rogue production.

Dr Luke Western, from the University of Bristol, a co-lead author of one ...

When we tear a muscle " stem cells within it repair the problem. We can see this occurring not only in severe muscle wasting diseases such as muscular dystrophy and in war veterans who survive catastrophic limb injuries, but also in our day to day lives when we pull a muscle.

Also when we age and become frail we lose much of our muscle and our stem cells don't seem to be able to work as well as we age.

These muscle stem cells are invisible engines that drive the tissue's growth and repair after such injuries. But growing these cells in the lab and then using them to therapeutically replace damaged muscle has been frustratingly difficult.

Researchers at the Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, ...

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) reveal that newly formed embryos clear dying cells to maximise their chances of survival. It is the earliest display of an innate immune response found in vertebrate animals to date.

The findings, which are published today in the journal Nature, may aid future efforts to understand why some embryos fail to form in the earliest stages of development, and lead to new clinical efforts in treating infertility or early miscarriages.

An embryo is fragile in the first hours after its formation. Rapid cell division and environmental stress make them prone to cellular errors, which in turn cause the sporadic death of embryonic stem cells. This is ...