(Press-News.org) In the last 25 years, scientists have discovered over 4000 planets beyond the borders of our solar system. From relatively small rock and water worlds to blisteringly hot gas giants, the planets display a remarkable variety. This variety is not unexpected. The sophisticated computer models, with which scientists study the formation of planets, also spawn very different planets. What the models have more difficulty to explain is the observed mass distribution of the planets discovered around other stars. The majority have fallen into the intermediate mass category - planets with masses of several Earth masses to around that of Neptune. Even in the context of the solar system, the formation of Uranus and Neptune remains a mystery. Scientists of the Universities of Zurich and Cambridge, associated with the Swiss NCCR PlanetS, have now proposed an alternative explanation backed up by comprehensive simulations. Their results were published in the scientific journal Nature Astronomy.

Two contrasting forces...

"When planets form from the so-called protoplanetary disk of gas and dust, gravitational instabilities could be the driving mechanism", Lucio Mayer, study co-author and Professor of Computational Astrophysics at the University of Zurich, and member of the NCCR PlanetS, explains. In this process, dust and gas in the disk clump together due to gravity and form dense spiral structures. These then grow into planetary building blocks and eventually planets.

The scale on which this process occurs is very large - spanning the scale of the protoplanetary disk. "But over shorter distances - the scale of single planets - another force dominates: That of magnetic fields developing alongside the planets", Mayer elaborates. These magnetic fields stir up the gas and dust of the disk and thus influence the formation of the planets. "To get a complete picture of the planetary formation process, it is therefore important to not only simulate the large scale spiral structure in the disk. The small scale magnetic fields around the growing planetary building blocks also have to be included", says lead-author of the study, former doctoral student of Mayer and now Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge, Hongping Deng.

...that are difficult to grasp simultaneously

However, the differences in scale and nature of gravity and magnetism make the two forces very challenging to integrate into the same planetary formation model. So far, computer simulations that captured the effects of one of the forces well, usually did poorly with the other. To succeed, the team developed a new modelling technique. That required expertise in a number of different areas: First, they needed a deep theoretical understanding of both gravity and magnetism. Then, the researchers had to find a way to translate the understanding into a code that could efficiently compute these contrasting forces in unison. Finally, due to the immense number of necessary calculations, a powerful computer was required - like the "Piz Daint" at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS). "Apart from the theoretical insights and the technical tools that we developed, we were therefore also dependent on the advancement of computing power", Lucio Mayer says.

A decades old puzzle solved?

Against the odds, everything came together at the right time and enabled a breakthrough. "With our model, we were able to show for the first time that the magnetic fields make it difficult for the growing planets to continue accumulating mass beyond a certain point. As a result, giant planets become rarer and intermediate-mass planets much more frequent - similar to what we observe in reality", Hongping Deng explains.

"These results are only a first step, but they clearly show the importance of accounting for more physical processes in planet formation simulations. Our study helps to understand potential pathways to the formation of intermediate-mass planets that are very common in our galaxy. It also helps us understand the protoplanetary disks in general", Ravit Helled, study co-author and Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics at the University of Zurich and member of the NCCR PlanetS, concludes.

INFORMATION:

Publication details: Formation of intermediate-mass planets via magnetically controlled disk fragmentation, Hongping Deng, Lucio Mayer and Ravit Helled,

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-020-01297-6

DOI: 0.1038/s41550-020-01297-6

LAWRENCE -- Nearly every fall, as football teams return to the field, tragic stories of players falling ill and even dying of heat trauma make the headlines. What many don't consider is that marching band members -- who don heavy uniforms and perform in the same sweltering temperatures -- may also be at risk.

A study led by the University of Kansas has measured core temperatures, hydration and sweat levels of marching band members and found that they are very much at risk and deserve access to athletic trainers for their safety -- just as players do.

The study used high tech methods to gauge band members' body core ...

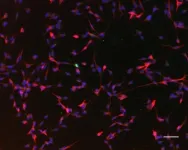

A study led by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine reveals a novel role of the steroid receptor coactivator 3 (SRC-3/NCOA3), a protein crucial for steroid hormone function and a prognostic marker for aggressive human breast and other cancers.

The team discovered that SRC-3 also regulates human immune T regulatory cells (Tregs), which contribute to the regulation of the body's immunological activity by suppressing the function of other immune cells, including those involved in fighting cancer. The study, which appears in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that Tregs whose SRC-3 function was eliminated failed to suppress the activity of other immune cells in the lab. The authors anticipate that their findings ...

The golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus lateralis) is a popular sight among tourists in the Rocky Mountains--the small rodent is a photogenic creature with a striped back and pudgy cheeks that store seeds and other food.

But there's a reality that Instagram photos don't capture, said Christy McCain, an ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. In a new study spanning nearly 13 years, she and her colleagues discovered that the ground squirrel has joined many other small mammals in Colorado's Rocky Mountains that are making an ominous trek: They're climbing uphill to avoid warming temperatures in the state brought on by climate change.

"It's frightening," ...

Globular clusters are extremely dense stellar systems, in which stars are packed closely together. They are also typically very old -- the globular cluster that is the focus of this study, NGC 6397, is almost as old as the Universe itself. It resides 7800 light-years away, making it one of the closest globular clusters to Earth. Because of its very dense nucleus, it is known as a core-collapsed cluster.

When Eduardo Vitral and Gary A. Mamon of the Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris set out to study the core of NGC 6397, they expected to find evidence for an "intermediate-mass" black hole (IMBH). These are smaller than the supermassive black holes that lie at the cores of large galaxies, but larger than stellar-mass black holes ...

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) develops as a long term complication of childhood streptococcal angina. Latent RHD can be detected with echocardiography years before it becomes symptomatic. RHD is curable when treated early with medication.

RHD is responsible for over 300 000 deaths worldwide each year, accounting for just over two-thirds of all deaths from valvular heart diseases. RHD is disproportionally prevalent across sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and the Pacific Islands and largely a phenomenon of marginalized communities in developing and emerging countries whereas ...

Millions of tonnes of plastic waste find their way into the ocean every year. A team of researchers from the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) in Potsdam has investigated the role of regional ocean governance in the fight against marine plastic pollution, highlighting why regional marine governance should be further strengthened as negotiations for a new global agreement continue.

In recent years, images of whales and sea turtles starving to death after ingesting plastic waste or becoming entangled in so-called ghost nets have led to a growing ...

Domestic cats are a major threat to wild species, including birds and small mammals. But researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 11 now have evidence that some simple strategies can help to reduce cats' environmental impact without restricting their freedom. Their studies show that domestic cats hunt less when owners feed them a diet including plenty of meat proteins. Equally, it helps to play with them each day in ways that allow cats to mimic hunting.

"While keeping cats indoors is the only sure-fire way to prevent hunting, some owners ...

Domestic cats hunt wildlife less if owners play with them daily and feed them a meat-rich food, new research shows.

Hunting by cats is a conservation and welfare concern, but methods to reduce this are controversial and often rely on restricting cat behaviour in ways many owners find unacceptable.

The new study - by the University of Exeter - found that introducing a premium commercial food where proteins came from meat reduced the number of prey animals cats brought home by 36%, and also that five to ten minutes of daily play with an owner resulted ...

Cambridge, MA - February 11, 2020 - Dyno Therapeutics, a biotech company applying artificial intelligence (AI) to gene therapy, today announced a publication in Nature Biotechnology that demonstrates the use of artificial intelligence to generate an unprecedented diversity of adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsids towards identifying functional variants capable of evading the immune system, a factor that is critical to enabling all patients to benefit from gene therapies. The research was conducted in collaboration with Google Research, Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and the Harvard Medical School laboratory of George M. Church, Ph.D., a Dyno scientific co-founder. The publication is entitled "Deep diversification ...

Natural compounds found in apples and other fruits may help stimulate the production of new brain cells, which may have implications for learning and memory, according to a END ...