(Press-News.org) MUSC Hollings Cancer Center researcher Yongxia Wu, Ph.D., identified a new target molecule in the fight against graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Bone marrow transplant, a treatment for certain blood cancers, is accompanied by potentially life-threatening GVHD in nearly 50% of patients. A January 2021 paper published in Cellular and Molecular Immunology revealed that activating a molecule called STING may be a new approach to reduce GVHD.

Xue-Zhong Yu, M.D., professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, focuses on understanding the intricate immune mechanisms that regulate GVHD development and anti-tumor activity.

Recently, STING (stimulator of interferon genes) has been highly studied in the context of cancer. Data from other groups has shown that STING activation in T cells helps the immune cells fight cancer. Cancer cells are essentially a "bad" version of the body's own cells and an appropriate target for its immune system. In contrast, in the case of GVHD, T cells fight the body's own "good" cells - in essence, the body attacks itself. Based on the previous data, it seemed logical that high STING activation, though good when it comes to cancer, would be bad in the context of GVHD. Yu's findings in a mouse model of GVHD confirmed this hypothesis. In the mouse model, which was obtained from collaborator Chih-Chi Andrew Hu, Ph.D., a Wistar Institute professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, GVHD was induced by bone marrow transplant, which closely models the disease development in humans.

To understand how GVHD develops after bone marrow transplantation, one must consider two immune systems: the donor's and the recipient's. The key immune cells are the antigen-presenting cells and the T cells. The immune system knows what to attack based on specific "tags," called antigens, that are shown to the T cells by the specialized antigen-presenting cells. Dendritic cells are the most effective antigen-presenting cells, and they play a critical role in GVHD.

Work from other research groups in cancer has demonstrated that STING signaling can regulate antigen- presenting cell function. STING is an important molecule in a DNA-sensing pathway that results in the production of inflammatory cytokines. But it is not known how STING regulates these cells in the context of GVHD.

The researchers used the mouse models to determine whether GVHD improved or worsened when STING was 1) absent in the donor immune cells, 2) absent in the recipient immune cells and 3) overexpressed in the recipient immune cells. GVHD severity was not changed when STING was absent from the donor immune cells. However, GVHD was more severe and mortality rates were higher when STING was missing from the recipient immune cells.

Yu and collaborators then looked at different cell subsets to try and understand which cells were most impacted by the loss of STING. Surprisingly, STING expression in the recipient mouse's antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells) reduced donor T cell expansion and migratory ability after bone marrow transplant. In other words, it made it less likely that the T cells of the recipient mouse would attack its "good" cells and lead to GVHD. This finding was confirmed using a pharmacological drug that turned on the STING molecule. Activating STING in the host before transplantation reduced GVHD severity.

The finding in a mouse model that activating STING with a pharmacological drug reduced GVHD could be clinically relevant in that it suggests the possibility that a STING-activating drug might protect bone marrow transplant recipients from GVHD. Much more basic and clinical research will be required to assess that possibility, but Yu's findings suggest that such research is warranted.

To understand why the research team observed what they did, they will continue to unravel the biological functions of the STING molecule. Unanswered questions include what makes STING function differently in different immune cell subsets.

"Tools such as the mice from our collaborator allow us to study this more thoroughly. Total-body deletion of a protein does not allow for specific study in cell subsets, and we think that STING must have different roles in different cells," explained Yu.

INFORMATION:

About MUSC

Founded in 1824 in Charleston, MUSC is the oldest medical school in the South, as well as the state's only integrated, academic health sciences center with a unique charge to serve the state through education, research and patient care. Each year, MUSC educates and trains more than 3,000 students and nearly 800 residents in six colleges: Dental Medicine, Graduate Studies, Health Professions, Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy. The state's leader in obtaining biomedical research funds, in fiscal year 2019, MUSC set a new high, bringing in more than $284 million. For information on academic programs, visit musc.edu.

As the clinical health system of the Medical University of South Carolina, MUSC Health is dedicated to delivering the highest quality patient care available, while training generations of competent, compassionate health care providers to serve the people of South Carolina and beyond. Comprising some 1,600 beds, more than 100 outreach sites, the MUSC College of Medicine, the physicians' practice plan, and nearly 275 telehealth locations, MUSC Health owns and operates eight hospitals situated in Charleston, Chester, Florence, Lancaster and Marion counties. In 2019, for the fifth consecutive year, U.S. News & World Report named MUSC Health the No. 1 hospital in South Carolina. To learn more about clinical patient services, visit muschealth.org.

MUSC and its affiliates have collective annual budgets of $3.2 billion. The more than 17,000 MUSC team members include world-class faculty, physicians, specialty providers and scientists who deliver groundbreaking education, research, technology and patient care.

About MUSC Hollings Cancer Center

MUSC Hollings Cancer Center is a National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center and the largest academic-based cancer research program in South Carolina. The cancer center comprises more than 100 faculty cancer scientists and 20 academic departments. It has an annual research funding portfolio of more than $44 million and a dedication to reducing the cancer burden in South Carolina. Hollings offers state-of-the-art diagnostic capabilities, therapies and surgical techniques within multidisciplinary clinics that include surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation therapists, radiologists, pathologists, psychologists and other specialists equipped for the full range of cancer care, including more than 200 clinical trials. For more information, visit hollingscancercenter.musc.edu.

Irvine, CA - February 11, 2021 - Subconsciously, our bodies keep time for us through an ancient means - the circadian clock. A new University of California, Irvine-led article reviews how the clock controls various aspects of homeostasis, and how organs coordinate their function over the course of a day.

"What is fascinating is that nearly every cell that makes up our organs has its own clock, and thus timing is a crucial aspect of biology," said Kevin B. Koronowski, PhD, lead author and a postdoctoral fellow in Biological Chemistry at the UCI School of Medicine. "Understanding how daily timing is integrated with function ...

A Russian physicist and his international colleagues studied a quantum point contact (QCP) between two conductors with external oscillating fields applied to the contact. They found that, for some types of contacts, an increase in the oscillation frequency above a critical value reduced the current to zero - a promising mechanism that can help create nanoelectronics components. This research supported by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF) was published in the Physical Review B journal.

A persistent trend in the modern electronics, miniaturization has spurred demand for new nano-sized devices that boast advanced performance and leverage quantum effects with electrons ...

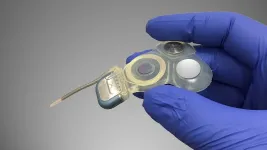

Getting around without the need to concentrate on every step is something most of us can take for granted because our inner ears drive reflexes that make maintaining balance automatic. However, for about 1.8 million adults worldwide with bilateral vestibular hypofunction (BVH) -- loss of the inner ears' sense of balance -- walking requires constant attention to avoid a fall. Now, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers have shown that they can facilitate walking, relieve dizziness and improve quality of life in patients with BVH by surgically implanting a stimulator that electrically ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - The songs of fin whales can be used for seismic imaging of the oceanic crust, providing scientists a novel alternative to conventional surveying, a new study published this week in Science shows.

Fin whale songs contain signals that are reflected and refracted within the crust, including the sediment and the solid rock layers beneath. These signals, recorded on seismometers on the ocean bottom, can be used to determine the thickness of the layers as well as other information relevant to seismic research, said John Nabelek, a professor in Oregon State University's College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and a co-author of the paper.

"People in the past have used whale calls to track whales and study whale behavior. ...

For some 15,000 years, dogs have been our hunting partners, workmates, helpers and companions. Could they also be our next allies in the fight against COVID-19?

According to UC Santa Barbara professor emeritus Tommy Dickey(link is external) and his collaborator, BioScent researcher Heather Junqueira, they can. And with a review paper(link is external) published in the Journal of Osteopathic Medicine they have added to a small but growing consensus that trained medical scent dogs can effectively be used for screening individuals who may be infected with the COVID-19 virus.

This follows a comprehensive survey of research ...

DURHAM, N.C. - People who have a gene variant associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease also tend to have changes in the fluid around their brain and spinal cord that are detectable years before symptoms arise, according to new research from Duke Health.

The work found that in people who carry the APOE4 gene variant, which is found in roughly 25 percent of the population, the cerebrospinal fluid contains lower levels of certain inflammatory molecules. This raises the possibility that these inflammatory molecules may be collecting in the brain where they may be damaging synapses, rather than floating freely in the cerebrospinal fluid.

The findings, which were published online last month in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, provide a potential ...

A team of researchers from Russia and Israel applied a new algorithm to classify the severity of autistic personality traits by studying subjects' brain activity.

The article 'Brief Report: Classification of Autistic Traits According to Brain Activity Recoded by fNIRS Using ε-Complexity Coefficients' is published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

When diagnosing autism and other mental disorders, physicians increasingly use neuroimaging methods in addition to traditional testing and observation. Such diagnostic methods are not only ...

Using a dataset on daily patrols and enforcement activities of officers in the Chicago Police Department (CPD) - an agency that has undergone substantial diversification in recent decades - researchers report Black officers used force less often than white officers during the three-year period studied, and women used force less often than men. These and other findings provide insight into impacts of diversification in policing, a widely proposed policing reform. "The magnitude of the differences [here] provides strong evidence that--at least in some cities--the number of officers who identify with vulnerable groups can matter quite a bit in predicting police behavior," writes Philip Goff in a related Perspective. Racial disparities in police-civilian interactions ...

Fin whale song - one of the strongest animal calls in the ocean - can be used as a seismic source for probing the structure of Earth's crust at the seafloor, researchers report. While the novel method produces lower-resolution results compared to the high-energy air-gun signals commonly used in seismic ocean surveys, the abundant and globally available fin whale calls could complement and enhance seismic studies where conventional techniques cannot be used. Surveying the structure of the ocean crust often requires powerful seismic waves. This is most commonly done using ship-based ...

During the Proterozoic, Earth grew no taller - the tectonic processes that form mountains stalled, leaving continents devoid of high mountains for nearly 1 billion years, according to a new study. Because mountain formation is crucial to nutrient cycling, the prolonged shift in crustal activity may have resulted in the "boring billion," an eon in which the evolution of Earth's life stalled. Over geologic timescales, even mountains are ephemeral. The massive tectonic forces that drive vast swaths of the planet skywards are countered by the interminable processes of erosion. Because the thickness of Earth's crust is in constant flux, tracking mountain formation over deep time is challenging, yet crucial to understanding the evolution of the planet's surface and the life that lives upon it. ...