(Press-News.org) Coral reefs have thrived for millions of years in their shallow ocean water environments due to their unique partnerships with the algae that live in their tissues. Corals provide a safe haven and carbon dioxide while their algal symbionts provide them with food and oxygen produced from photosynthesis. Using the corals Orbicella annularis and Orbicella faveolate in the southern Caribbean, researchers at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB) have improved our ability to visualize and track these symbiotic interactions in the face of globally warming sea surface temperatures and deepening seawaters.

"Corals are one of the most resilient organisms on the planet," said Mayandi Sivaguru, the co-lead author of the study and Assistant Director of Core Facilities at the IGB. "They have survived ice ages, greenhouse conditions with no ice, and everything else in between that the planet has thrown at them."

Although they have a long history of weathering disruptions, coral reefs are also sensitive enough to serve as indicators of climate change and oceanic health. As an example, when the sea surface temperature or the seawater acidity increases, corals eject their algal partners--a phenomenon called coral bleaching--which converts the corals from green to white. To understand why bleaching occurs, it is important to visualize how the corals interact with their algal partners.

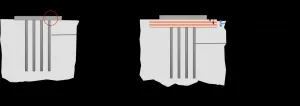

Previously, researchers had to peel the skin of corals and place the samples in a blender to study their symbiotic algal partners. The current study uses a non-invasive technique instead. "We collect small samples of corals on the living reef, bring them back to Illinois, and look at them under the microscope without further processing. Two-photon microscopy allows us to look at their three-dimensional structure, and determine how many algae and what biomolecules are present," Sivaguru said. The technique uses light to scan living tissues, allowing the researchers to keep the corals in their original growth structure.

The researchers used these new methods to compare the symbionts in two environmental contexts. The first was from shallow to deeper seawater and the second was between seasonal warm-to-cool changes in sea surface temperatures. "In addition to analyzing the number of symbionts in the coral tissues, which the corals can alter, we also tracked simultaneous changes in mucus and biomolecules produced by the corals, some of which serve as a natural sun block," Sivaguru said.

The microscopy studies revealed that shallow water corals have lower algal concentrations and produce higher levels of chromatophores, which are biomolecules that protect algae from sunlight damage. On the other hand, the researchers found the opposite pattern in deeper water corals. These corals receive lesser sunlight and would therefore require more algae to keep up with the photosynthetic demand. During seasonal sea surface temperature changes, the warmer water caused decreased mucus production and algal concentrations, but increased photosynthesis and coral skeleton growth. Conversely, cooler waters caused the opposite effect.

"We have combined the results of this study to identify universal mechanisms of biomineralization found between water, microbes, living organisms, and rock," said Lauren Todorov, the co-lead author, who completed this research as part of her undergraduate B.Sc. thesis at Illinois and is now completing her M.Sc. in Geology. "This study has allowed us to establish a comprehensive understanding of the coral system as well as make connections to the formation of layered rock in other systems such as hot springs, roman aqueducts, and even human kidney stones."

"This project required several years to complete and required virtually all of the microscopes available in the IGB Core Facilities. Importantly, our research team included several students who worked on the project starting in high school and continued as part of their undergraduate and graduate research in institutions across the United States. This included fieldwork in Curaçao and well as work at the IGB," said Bruce Fouke (BCXT), a professor of geology and microbiology at the IGB.

INFORMATION:

The study "Corals regulate the distribution and abundance of Symbiodiniaceae and biomolecules in response to changing water depth and sea surface temperature" was published in Scientific Reports and can be found at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-81520-0.

The work was funded by the Office of Naval Research, the IGB Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship, the IGB Mark Tracy Fellowship for Translational Research, the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology Jenner Family Summer Research Fellowship, and the Edward and Barbara Weil Research Fund.

In coming decades as coastal communities around the world are expected to encounter sea-level rise, the general expectation has been that people's migration toward the coast will slow or reverse in many places.

However, new research co-authored by Princeton University shows that migration to the coast could actually accelerate in some places despite sea-level change, contradicting current assumptions.

The research, published in Environmental Research Letters, uses a more complex behavioral decision-making model to look at Bangladesh, whose coastal zone is at high risk. They found job opportunities are most abundant in coastal cities across Bangladesh, attracting more ...

It's no secret that the risk related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) increases with age, making older adults more vulnerable than younger people.

Less examined has been effects on pregnancy and birthing. According to a new study led by Sarah DeYoung, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, and Michaela Mangum, a master's student in disaster science and management, the pandemic causes additional stress for people who were pregnant or gave birth during the pandemic. The stress was especially prevalent if the person ...

A new study from the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai shows that women have a lower “normal” blood pressure range compared to men. The findings were published today in the peer-reviewed journal Circulation.Currently, established blood pressure guidelines state that women and men have the same normal healthy range of blood pressure. But the new research shows there are differences in normal blood pressure between the sexes.“Our latest findings suggest that this one-size-fits-all approach to considering blood pressure may be detrimental to a woman’s health,” ...

Mammals and cold-blooded alligators share a common four-chamber heart structure - unique among reptiles - but that's where the similarities end. Unlike humans and other mammals, whose hearts can fibrillate under stress, alligators have built-in antiarrhythmic protection. The findings from new research were reported Jan. 27 in the journal Integrative Organismal Biology.

"Alligator hearts don't fibrillate - no matter what we do. They're very resilient," said Flavio Fenton, a professor in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, researcher ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- Throughout her career, Lori Popejoy provided hands-on clinical care in a variety of health care settings, from hospitals and nursing homes to community centers and home health care agencies. She became interested in the area of care coordination, as patients who are not properly cared for after being discharged from the hospital often end up being readmitted in a sicker, more vulnerable state of health.

Now an associate professor in the University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing, Popejoy and her research team conducted a study to determine the most effective way patients ...

Metabolic diseases, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, have risen to epidemic proportions in the U.S. and occur in about 30 percent of the population. Skeletal muscle plays a prominent role in controlling the body's glucose levels, which is important for the development of metabolic diseases like diabetes.

In a recent study, published in END ...

Investigators at the University of Chicago Medicine have found that women are less likely to be represented as chairs and reviewers on study sections for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), based on data from one review cycle in 2019. The results, published on Feb. 15 in JAMA Network Open, have implications for the distribution of federal scientific funding.

The NIH is the top source of federal funding for biomedical research in the U.S., providing critical support and guidance on the nation's research programs. The study sought to understand the gender distribution ...

New research from North Carolina State University has found that Campylobacter bacteria persist throughout poultry production - from farm to grocery shelves - and that two of the most common strains are exchanging genetic material, which could result in more antibiotic-resistant and infectious Campylobacter strains.

Campylobacter is a well-known group of foodborne bacteria, spread primarily through consumption of contaminated food products. In humans it causes symptoms commonly associated with food poisoning, such as diarrhea, fever and cramps. However, Campylobacter infections also constitute one of the leading precursors ...

Surface rupturing during earthquakes is a significant risk to any structure that is built across a fault zone that may be active, in addition to any risk from ground shaking. Surface rupture can affect large areas of land, and it can damage all structures in the vicinity of the fracture. Although current seismic codes restrict the construction in the vicinity of active tectonic faults, finding the exact location of fault outcrop is often difficult.

In many regions around the world, engineering structures such as earth dams, buildings, pipelines, landfills, bridges, roads and railroads have been built in areas very close to active fault segments. Strike-slip fault rupture occurs when the rock masses slip past each other ...

Cancer cells and immune cells share something in common: They both love sugar.

Sugar is an important nutrient. All cells use sugar as a vital source of energy and building blocks. For immune cells, gobbling up sugar is a good thing, since it means getting enough nutrients to grow and divide for stronger immune responses. But cancer cells use sugar for more nefarious ends.

So, what happens when tumor cells and immune cells battle for access to the same supply of sugar? That's the central question that Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers Taha Merghoub, Jedd Wolchok, and Roberta Zappasodi explore in a new study published February 15 in the journal Nature.

Using mouse models and data ...