(Press-News.org) It is almost ten years since the scientific journal Science called optogenetics the "breakthrough of the decade". Put simply, the technique makes it possible to control the electrical activity of cells with pulses of light. With its help, scientists can gain new insights into the functioning of nerve cells, for example, and thus better understand neurological and psychiatric diseases such as depression and schizophrenia.

Established procedure on animal cells

In research on animal cells, optogenetics is now an established technique used in many fields. The picture is different in plant research: transferring the principle to plant cells and applying it widely has not been possible until now.

However, this has now changed: Scientists at the Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg (JMU) have succeeded in applying optogenetic methods in tobacco plants. They present the results of their work in the current issue of the journal Nature Plants. "In particular, Dr. Kai Konrad from Prof. Hedrich's group (Botany I) and Dr. Shiqiang Gao from my group were mainly responsible for the success of this project" explains Professor Georg Nagel, co-founder of optogenetics. In addition to the Department of Neurophysiology in the Institute of Physiology, three chairs of the Julius-von-Sachs Institute were involved in the collaboration: Botany I, Botany II and Pharmaceutical Biology.

Light switch for cell activity

"Optogenetics is the manipulation of cells or living organisms by light after a 'light sensor' has been introduced into them using genetic engineering methods. In particular, the light-controlled cation channel channelrhodopsin-2 has helped optogenetics achieve a breakthrough," says Nagel, describing the method he co-developed. With the help of channelrhodopsin, the activity of cells can be switched on and off as if with a light switch.

In plant cells, however, this has so far only worked to a limited extent. There are two main reasons for this: "It is difficult to genetically modify plants so that they functionally produce rhodopsins. In addition, they lack a crucial cofactor without which rhodopsins cannot function: all-trans retinal, also known as vitamin A," explains Dr. Gao.

Green light for plant cells

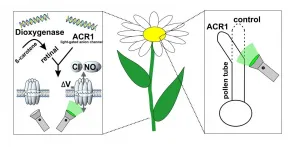

Prof. Nagel, Dr. Gao, Dr. Konrad, and colleagues have now been able to solve both problems. They have succeeded in producing vitamin A in tobacco plants by means of an introduced enzyme from a marine bacterium, thus enabling improved incorporation of rhodopsin into the cell membrane. This allows, for the first time, non-invasive manipulation of intact plants or selected cells by light via the so-called anion channel rhodopsin GtACR1.

In an earlier approach, plant physiologists from Botany I had artificially added the much-needed cofactor vitamin A to cells to allow a light-gated cation channel to become active in plant cells (Reyer et al., 2020, PNAS). Using the genetic trick now presented, Prof. Nagel and colleagues have generated plants that produce a special enzyme in addition to a rhodopsin, called dioxygenase. These plants are then able to produce vitamin A - which is normally not present in plants - from provitamin A which is abundant in the plant chloroplast. The combination of vitamin A production and optimization of rhodopsins for plant application ultimately led the researchers led by Prof. Nagel, Dr. Konrad and Dr. Gao to success.

New approach for plant research

"If you irradiate these cells with green light, the permeability of the cell membrane for negatively charged particles increases sharply, and the membrane potential changes significantly," explains Dr. Konrad. In this way, he says, it is possible to specifically manipulate the growth of pollen tubes and the development of leaves, for example, and thus to study the molecular mechanisms of plant growth processes in detail. The Würzburg researchers are confident that this novel optogenetic approach to plant research will greatly facilitate the analysis of previously misunderstood signaling pathways in the future.

A pioneer of optogenetics

Rhodopsin is a naturally light-sensitive pigment that forms the basis of vision in many living organisms. The fact that a light-sensitive ion pump from archaebacteria (bacteriorhodopsin) can be incorporated into vertebrate cells and function there was first demonstrated by Georg Nagel in 1995 together with Ernst Bamberg at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysics in Frankfurt. In 2002/2003, this proof was then also achieved with light-sensitive ion channels from algae.

Together with Peter Hegemann, Nagel demonstrated the existence of two light-sensitive channel proteins, channelrhodopsin-1 and channelrhodopsin- 2 (ChR1/ChR2), in two papers published in 2002 and 2003. Crucially, the researchers discovered that ChR2 elicits an extremely rapid, light-induced change in membrane current and membrane voltage when the gene is expressed in vertebrate cells. In addition, ChR2's small size makes it very easy to use.

Nagel has since then received numerous awards for this discovery, most recently in 2020 - together with two other pioneers of optogenetics - the $1.2 million Shaw Prize for Life Sciences.

INFORMATION:

Individual variation in the shape and structure of the Achilles tendon may influence our susceptibility to injury later in life, says a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that studying individual Achilles tendon shape (or 'morphology') could help with identifying patients at risk of injury and designing new, potentially personalised approaches for treating and preventing Achilles tendinopathy and similar conditions.

The Achilles tendon is the tissue that links the calf muscles to the heel bone. It is fundamental to our movement and athletic ability. Its unique structure, which combines three smaller sub-tendons, increases the efficiency of our movement by allowing individual control from connected muscles. For this control to occur, the ...

A drug that helps us to eat less could help the more than 650 million people around the world who live with obesity. One of the emerging drug candidates that interest researchers is the hormone GDF15 that, when given to rodents, lowers their appetite and body weight. New research from the University of Copenhagen finds that the body produces large amounts GDF15 during extended bouts of vigorous exercise, presumably as a physiological stress signal.

This finding highlights central differences between GDF15 given as a drug (pharmacology), and GDF15 released naturally in response to vigorous exercise (physiology). This is an important distinction ...

From 2015 to 2019, public school districts in the United States invested nearly $5 billion to upgrade their Wi-Fi networks, according to EducationSuperHighway. However, in the age of COVID-19-mandated virtual learning, millions of K-12 students still lack the minimal connectivity at home for digital learning.

In a new study from the University of Notre Dame, researchers quantify how school district connectivity increases test scores, but underscore the dark side of technology -- increased behavior problems.

A $600,000 increase in annual internet access spending produces a financial gain of approximately $820,000 to $1.8 million, alongside losses from disciplinary problems totaling $25,800 to $53,440, according to new research from Yixing Chen, an ...

Researchers at the University of Chicago, the University of Birmingham, and Bournemouth University have uncovered evidence that physical embodiment can occur without the sense of touch, thanks to a study involving two participants who lack the ability to feel touch. The research was published on Feb. 12 in END ...

Coral reefs have thrived for millions of years in their shallow ocean water environments due to their unique partnerships with the algae that live in their tissues. Corals provide a safe haven and carbon dioxide while their algal symbionts provide them with food and oxygen produced from photosynthesis. Using the corals Orbicella annularis and Orbicella faveolate in the southern Caribbean, researchers at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB) have improved our ability to visualize and track these symbiotic interactions in the face of globally warming sea surface temperatures and ...

In coming decades as coastal communities around the world are expected to encounter sea-level rise, the general expectation has been that people's migration toward the coast will slow or reverse in many places.

However, new research co-authored by Princeton University shows that migration to the coast could actually accelerate in some places despite sea-level change, contradicting current assumptions.

The research, published in Environmental Research Letters, uses a more complex behavioral decision-making model to look at Bangladesh, whose coastal zone is at high risk. They found job opportunities are most abundant in coastal cities across Bangladesh, attracting more ...

It's no secret that the risk related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) increases with age, making older adults more vulnerable than younger people.

Less examined has been effects on pregnancy and birthing. According to a new study led by Sarah DeYoung, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, and Michaela Mangum, a master's student in disaster science and management, the pandemic causes additional stress for people who were pregnant or gave birth during the pandemic. The stress was especially prevalent if the person ...

A new study from the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai shows that women have a lower “normal” blood pressure range compared to men. The findings were published today in the peer-reviewed journal Circulation.Currently, established blood pressure guidelines state that women and men have the same normal healthy range of blood pressure. But the new research shows there are differences in normal blood pressure between the sexes.“Our latest findings suggest that this one-size-fits-all approach to considering blood pressure may be detrimental to a woman’s health,” ...

Mammals and cold-blooded alligators share a common four-chamber heart structure - unique among reptiles - but that's where the similarities end. Unlike humans and other mammals, whose hearts can fibrillate under stress, alligators have built-in antiarrhythmic protection. The findings from new research were reported Jan. 27 in the journal Integrative Organismal Biology.

"Alligator hearts don't fibrillate - no matter what we do. They're very resilient," said Flavio Fenton, a professor in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, researcher ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- Throughout her career, Lori Popejoy provided hands-on clinical care in a variety of health care settings, from hospitals and nursing homes to community centers and home health care agencies. She became interested in the area of care coordination, as patients who are not properly cared for after being discharged from the hospital often end up being readmitted in a sicker, more vulnerable state of health.

Now an associate professor in the University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing, Popejoy and her research team conducted a study to determine the most effective way patients ...