(Press-News.org) Icebergs are melting faster than current models describe, according to a new study by mathematicians at the University of Sydney. The researchers have proposed a new model to more accurately represent the melt speed of icebergs into oceans.

Their results, published in Physical Review Fluids, have implications for oceanographers and climate scientists.

Lead author and PhD student Eric Hester said: "While icebergs are only one part of the global climate system, our improved model provides us with a dial that we can tune to better capture the reality of Earth's changing climate."

Current models, which are incorporated into the methodology used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, assume that icebergs melt uniformly in ocean currents. However, Mr Hester and colleagues have shown that icebergs do not melt uniformly and melt at different speeds depending on their shape.

"About 70 percent of the world's freshwater is in the polar ice sheets and we know climate change is causing these ice sheets to shrink," said Mr Hester, a doctoral student in the School of Mathematics & Statistics.

"Some of this ice loss is direct from the ice sheets, but about half of the overall ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica happens when icebergs melt in the ocean, so understanding this process is important.

"Our model shows that icebergs are melting at faster rates than current models assume," he said.

As well as its importance for modelling how ice sheets are changing, Mr Hester said his research will help us better understand the impact of ice melt on ocean currents.

"Ocean circulation is the reason that Britain isn't as cold as Alberta, Canada, despite being at similar latitudes," Mr Hester said.

The Gulf Stream that takes warmer water from the tropics across the Atlantic keeps western Europe milder than it otherwise would be, he said.

"That current could shut down if too much freshwater is dumped into the system at once, so it's critical we understand the process of iceberg and ice sheet melt."

Where and when the freshwater is released, and how the ocean is affected, in part depends on the speed at which icebergs melt.

Co-author Dr Geoffrey Vasil from the University of Sydney said: "Previous work incorporating icebergs in climate simulations used very simple melting models. We wanted to see how accurate those were and whether we could improve on them."

Mr Hester said their models - confirmed in experiment - and the observations of oceanographers show that the sides of icebergs melt about twice as fast as their base. For icebergs that are moving in the ocean, melting at the front can be three or four times faster than what the old models predicted.

"The old models assumed that stationary icebergs didn't melt at all, whereas our experiments show melting of about a millimetre every minute," Mr Hester said.

"In icebergs moving in oceans, the melting on the base can be up to 30 percent faster than in old models."

The research shows that iceberg shape is important. Given that the sides melt faster, wide icebergs melt more slowly but smaller, narrower icebergs melt faster.

"Our paper proposes a very simple model that accounts for iceberg shape, as a prototype for an improved model of iceberg melting," Dr Vasil said.

To test these models, the researchers developed the first realistic small-scale simulations of melting ice in salt water.

"We are confident this modelling captures enough of the complexity so that we now have a much better way to explain how icebergs melt," Mr Hester said.

Dr Vasil, who is Mr Hester's PhD supervisor, said: "Before Eric started his PhD the computational tools to model these kinds of systems didn't really exist.

"Eric took a very simple prototype and made it work wonderfully on the complex ice-melting problem."

Dr Vasil said that these methods can be applied to many other systems, including glaciers melting or the melting of frozen, saline sea ice.

"But it doesn't end there. His methods could also be used by astrobiologists to better understand ice moons like Saturn's Enceladus, a candidate for finding life elsewhere in the Solar System."

INFORMATION:

The research was done in collaboration with scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, University of Canterbury in New Zealand and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, USA.

DOWNLOAD a video of the experiment, the academic paper and photos at this link.

EMBED a YouTube video explainer (30 seconds) at this link.

READ an article about the research by the American Physical Society at this link.

INTERVIEWS

Eric Hester | eric.hester@sydney.edu.au

MEDIA ENQUIRIES

Marcus Strom | marcus.strom@sydney.edu.au | +61 423 982 485

DECLARATION

Eric Hester was partially funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) for his fellowship at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and by the William and Catherine McIlarth Travel Scholarship at the University of Sydney. Other researchers received partial funding from the EU Horizon program and the NSF. The researchers acknowledge access to the PRACE supercomputer at CINECA, Italy.

Over the past years, global data traffic has experienced a boom, with over 12.5 billion connected devices all over the world. The current world-wide deployment of the 5G telecommunications standard is triggering the need for smaller devices with enhanced performances, such as higher speed, lower power consumption and reduced cost as well as easier manufacturability.

In search for the appropriate technology, photonic devices emerged as the leading technology for the evolution of such information and communication technologies, already surpassing ...

ADELPHI, Md. -- The Army of the future will involve humans and autonomous machines working together to accomplish the mission. According to Army researchers, this vision will only succeed if artificial intelligence is perceived to be ethical.

Researchers, based at the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, now known as DEVCOM, Army Research Laboratory, Northeastern University and the University of Southern California, expanded existing research to cover moral dilemmas and decision making that has not been pursued elsewhere.

This research, featured in Frontiers in Robotics and AI, tackles the fundamental challenge of developing ethical artificial intelligence, ...

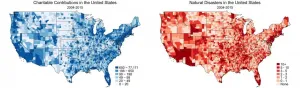

The human condition is riddled with extreme events, which bring chaos into our lives. Natural disasters leave a trail of destruction, causing direct and horrible pain and suffering - costing lives, creating injuries, destroying houses, livelihoods, crops and broken infrastructures. While extensive research has been conducted on the economic and public healthcare costs of these types of disasters around the world, their effect does not end there. A team of researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem sought to better understand the behavioral and social implications ...

Psychotherapy for panic disorder produces good results, and the effects are lasting. That is the result from a large long-term study from Lund University in Sweden. Two years after treatment were 70 per cent of the patients clearly improved and 45 per cent were remitted.

Panic disorder is one of the most common causes of mental illness in Sweden and worldwide. Approximately 2 per cent have panic disorder. When untreated, the condition is associated with emotional distress and social isolation. Panic attacks often debut in adolescence or early adulthood and many of those affected ...

We live in modern times, that is full of electronics. Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and many other devices need electrical energy to operate. Portable devices made our lives easier, so novel solutions in clean energy and its storage are desirable. Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries are the most common solutions that dominate the global market and are a huge problem due to their insufficient recovery. Because of their limited power, short cycle life, and non-environment-friendly nature, scientists recently focused on novel solutions like supercapacitors that offer much more than batteries. Why? Let's take a look closer at these devices.

Supercapacitors bring together the properties of a standard capacitor and the Li-ion battery. In practice, ...

Following the civil war outbreak in Syria nearly ten years ago, Israel began admitting wounded Syrians into the country for humanitarian medical treatment.

In accordance with the Israeli government's decision, the Israel Defense Forces, medical corps, health care system and hospitals in the north of the country joined together to provide medical treatment to thousands of wounded Syrians. The logistics of evacuating the injured from the battlefield and transferring them to Israeli territory was often prolonged due to the fact that Israel and Syria are defined as enemy countries.

Most of the wounded were brought to the Galilee ...

Biophysicists at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munch have developed a new theory, which accounts for the observation that cells can perceive their own shapes, and use this information to direct the distribution of proteins inside the cell.

Many cellular processes are critically dependent on the precise distribution and patterning of proteins on the cell membrane. Diverse studies have shown that, in addition to protein-protein interactions and transport processes, cell shape can also have a considerable impact on intracellular pattern formation. Conversely, there are patterning processes in which any dependence on cell form would be deleterious. Using starfish oocytes as a model system, LMU physicists led by Professor Erwin ...

In shallow water, less than 30 metres, the survival of hard corals depends on photosynthetic unicellular algae (zooxanthellae) living in their tissues. But how does the coral adapt at depth when the light disappears? French researchers from the CNRS, EPHE-PSL and their international collaborators, associated with Under the Pole (Expedition III), have studied for the first time the distribution of these so-called mesophotic corals in the French Polynesian archipelago, from the surface to 120 metres deep (with a record descent of 172 metres). As the amount of light decreases, the coral associates ...

DARIEN, IL - A new study found that treating obstructive sleep apnea with CPAP therapy increased self-reported physical activity in adults with a history of heart disease.

During a mean follow-up period of 3.7 years, the group treated with CPAP therapy reported approximately 20% higher levels of moderate physical activity compared with the control group. The study also found the CPAP group was more likely to report activity levels consistent with expert recommendations.

"We were pleased to find that our CPAP users reported that they were better able to maintain their levels of activity over the four years of the study, and that they reported fewer limitations in moderate and vigorous activities including those that are important for independent aging, like walking up the stairs," ...

The researchers used a biophysical method called thermal proteome profiling (TPP) to gain a comprehensive overview of which human proteins are functionally altered during SARS-CoV-2 infection. TPP monitors protein amounts and denaturation temperatures - the points at which proteins heat up so much that they lose their 3D structure. A shift in denaturation temperature indicates that a particular protein has undergone a functional change upon infection, possibly due to the virus hijacking the protein for use in its own replication.

The scientists observed that infection with SARS-CoV-2 changed the abundance and thermal stability of hundreds of cellular proteins. This included ...