Delayed medical treatment of high-impact injuries: A lesson from the Syrian civil war

In providing humanitarian medical treatment to victims of the Syrian civil war, Israeli researchers from the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University and Galilee Medical Center found that delayed surgical intervention may improve outcome.

2021-02-16

(Press-News.org) Following the civil war outbreak in Syria nearly ten years ago, Israel began admitting wounded Syrians into the country for humanitarian medical treatment.

In accordance with the Israeli government's decision, the Israel Defense Forces, medical corps, health care system and hospitals in the north of the country joined together to provide medical treatment to thousands of wounded Syrians. The logistics of evacuating the injured from the battlefield and transferring them to Israeli territory was often prolonged due to the fact that Israel and Syria are defined as enemy countries.

Most of the wounded were brought to the Galilee Medical Center (GMC) in northern Israel. Some were admitted within 24 hours of injury. For others, it took as long as 14-28 days to reach Israel from the combat zone.

The delay in the commencement of treatment provided medical professionals and researchers from GMC's Ear, Nose, and Throat Ward and Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a rare window of opportunity to observe and evaluate how this lapse in time impacted the outcome of treatment.

In a study recently published in the journal Scientific Reports, the researchers report, quite surprisingly, that patients injured in the facial bones by high-speed fire and operated on approximately 2-4 weeks after the injury suffered fewer post-operative complications compared to wounded who underwent immediate surgical treatment (within 72 hours). The researchers hypothesize that this is due to a critical period of time before surgery, which facilitates healing and formation of new blood vessels in the area of the injury and, subsequently, an improvement in the blood and oxygen supply and a reduction in the incidence of complications. Prof. Samer Srouji, member of the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University and Chief of the Oral and Maxillofacial Institute at GMC and lead author of the study, and colleagues coined the term Critical Revascularization Period (CRP) to explain this phenomenon.

"We believe that this benefit stems from neovascularization, the formation and repair - over time -- of blood vessels in the injured region, which improves the supply of blood and oxygen to the area and, in turn, leads to smoother healing and fewer complications following surgery," explains Prof. Srouji. "This study also highlights the important interface between bedside and basic research in the lab. We are currently working on 3D organ printing methods to develop artificial organ scaffold optimized for ideal oxygenation bone construction and rapid wound healing."

Treating the wounded civilians also provided insight into injuries caused by sniper fire and high-velocity injuries unique to a battlefield. The researchers have developed a laboratory model that simulates shooting injuries and they continue to collect and process data from the period of treatment of the wounded from the Syrian civil war.

The findings in this study may lead to a reassessment of protocols for the treatment of high-speed head and facial injuries. It is not yet possible to draw unequivocal conclusions concerning the ideal time for surgical treatment. However, the research findings indicate that delayed treatment, characterized by an opportunity for maxillofacial revascularization, can enhance surgical outcomes while simultaneously decreasing postoperative morbidity and complications.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-16

Biophysicists at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munch have developed a new theory, which accounts for the observation that cells can perceive their own shapes, and use this information to direct the distribution of proteins inside the cell.

Many cellular processes are critically dependent on the precise distribution and patterning of proteins on the cell membrane. Diverse studies have shown that, in addition to protein-protein interactions and transport processes, cell shape can also have a considerable impact on intracellular pattern formation. Conversely, there are patterning processes in which any dependence on cell form would be deleterious. Using starfish oocytes as a model system, LMU physicists led by Professor Erwin ...

2021-02-16

In shallow water, less than 30 metres, the survival of hard corals depends on photosynthetic unicellular algae (zooxanthellae) living in their tissues. But how does the coral adapt at depth when the light disappears? French researchers from the CNRS, EPHE-PSL and their international collaborators, associated with Under the Pole (Expedition III), have studied for the first time the distribution of these so-called mesophotic corals in the French Polynesian archipelago, from the surface to 120 metres deep (with a record descent of 172 metres). As the amount of light decreases, the coral associates ...

2021-02-16

DARIEN, IL - A new study found that treating obstructive sleep apnea with CPAP therapy increased self-reported physical activity in adults with a history of heart disease.

During a mean follow-up period of 3.7 years, the group treated with CPAP therapy reported approximately 20% higher levels of moderate physical activity compared with the control group. The study also found the CPAP group was more likely to report activity levels consistent with expert recommendations.

"We were pleased to find that our CPAP users reported that they were better able to maintain their levels of activity over the four years of the study, and that they reported fewer limitations in moderate and vigorous activities including those that are important for independent aging, like walking up the stairs," ...

2021-02-16

The researchers used a biophysical method called thermal proteome profiling (TPP) to gain a comprehensive overview of which human proteins are functionally altered during SARS-CoV-2 infection. TPP monitors protein amounts and denaturation temperatures - the points at which proteins heat up so much that they lose their 3D structure. A shift in denaturation temperature indicates that a particular protein has undergone a functional change upon infection, possibly due to the virus hijacking the protein for use in its own replication.

The scientists observed that infection with SARS-CoV-2 changed the abundance and thermal stability of hundreds of cellular proteins. This included ...

2021-02-16

Psycholinguists from the HSE Centre for Language and Brain found that when reading, people are not only able to predict specific words, but also words' grammatical properties, which helps them to read faster. Researchers have also discovered that predictability of words and grammatical features can be successfully modelled with the use of neural networks. The study was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The ability to predict the next word in another person's speech or in reading has been described by many psycho- and neurolinguistic studies over the last 40 years. It is assumed that this ability allows us to process the information faster. Some recent publications on the English language have demonstrated evidence that while reading, people can ...

2021-02-16

Canadian researchers are the first to study how different patterns in the way older adults walk could more accurately diagnose different types of dementia and identify Alzheimer's disease.

A new study by a Canadian research team, led by London researchers from Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University, evaluated the walking patterns and brain function of 500 participants currently enrolled in clinical trials. Their findings are published today in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association.

"We have longstanding evidence showing that cognitive problems, such as poor memory and executive dysfunction, can ...

2021-02-16

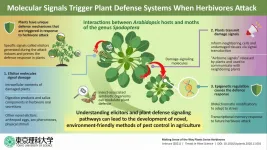

Nature has its way of maintaining balance. This statement rightly holds true for plants that are eaten by herbivores--insects or even mammals. Interestingly, these plants do not just silently allow themselves to be consumed and destroyed; in fact, they have evolved a defense system to warn them of predator attacks and potentially even ward them off. The defense systems arise as a result of inner and outer cellular signaling in the plants, as well as ecological cues. Plants have developed several ways of sensing damage; a lot of these involve the sensing of various "elicitor" molecules produced by either the predator ...

2021-02-16

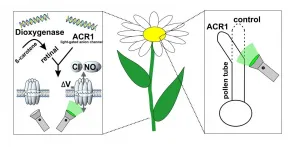

It is almost ten years since the scientific journal Science called optogenetics the "breakthrough of the decade". Put simply, the technique makes it possible to control the electrical activity of cells with pulses of light. With its help, scientists can gain new insights into the functioning of nerve cells, for example, and thus better understand neurological and psychiatric diseases such as depression and schizophrenia.

Established procedure on animal cells

In research on animal cells, optogenetics is now an established technique used in many fields. The picture is different in plant research: transferring the principle to plant cells and applying it widely has not been possible until now.

However, this has now changed: Scientists ...

2021-02-16

Individual variation in the shape and structure of the Achilles tendon may influence our susceptibility to injury later in life, says a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that studying individual Achilles tendon shape (or 'morphology') could help with identifying patients at risk of injury and designing new, potentially personalised approaches for treating and preventing Achilles tendinopathy and similar conditions.

The Achilles tendon is the tissue that links the calf muscles to the heel bone. It is fundamental to our movement and athletic ability. Its unique structure, which combines three smaller sub-tendons, increases the efficiency of our movement by allowing individual control from connected muscles. For this control to occur, the ...

2021-02-16

A drug that helps us to eat less could help the more than 650 million people around the world who live with obesity. One of the emerging drug candidates that interest researchers is the hormone GDF15 that, when given to rodents, lowers their appetite and body weight. New research from the University of Copenhagen finds that the body produces large amounts GDF15 during extended bouts of vigorous exercise, presumably as a physiological stress signal.

This finding highlights central differences between GDF15 given as a drug (pharmacology), and GDF15 released naturally in response to vigorous exercise (physiology). This is an important distinction ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Delayed medical treatment of high-impact injuries: A lesson from the Syrian civil war

In providing humanitarian medical treatment to victims of the Syrian civil war, Israeli researchers from the Azrieli Faculty of Medicine of Bar-Ilan University and Galilee Medical Center found that delayed surgical intervention may improve outcome.