Predicting words' grammatical properties helps us read faster

Such prediction can be successfully modelled by neural networks

2021-02-16

(Press-News.org) Psycholinguists from the HSE Centre for Language and Brain found that when reading, people are not only able to predict specific words, but also words' grammatical properties, which helps them to read faster. Researchers have also discovered that predictability of words and grammatical features can be successfully modelled with the use of neural networks. The study was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The ability to predict the next word in another person's speech or in reading has been described by many psycho- and neurolinguistic studies over the last 40 years. It is assumed that this ability allows us to process the information faster. Some recent publications on the English language have demonstrated evidence that while reading, people can not only predict specific words, but also their properties (e.g., the part of speech or the semantic group). Such partial prediction also helps us to read faster.

In order to access predictability of a certain word in a context, researchers usually use cloze tasks, such as The cause of the accident was a mobile phone, which distracted the ______. In this phrase, different nouns are possible, but driver is the most probable, which is also the real ending of the sentence. The probability of the word driver in the context is calculated as the number of people who correctly guessed this word over the total number of people who completed the task.

The other approach for predicting word probability in context is the use of language models that offer word probabilities relying on a big corpus of texts. However, there are virtually no studies that would compare the probabilities received from the cloze task to those from the language model. Additionally, no one has tried to model the understudied grammatical predictability of words. The authors of the paper decided to learn whether native Russian speakers would predict grammatical properties of words and whether the language model probabilities could become a reliable substitution to probabilities from cloze tasks.

The researchers analysed responses of 605 native Russian speakers in the cloze task in 144 sentences and found out that people can precisely predict the specific word in about 18% of cases. Precision of prediction of parts of speech and morphological features of words (gender, number and case of nouns; tense, number, person and gender of verbs) varied from 63% to 78%. They discovered that the neural network model, which was trained on the Russian National Corpus, predicts specific words and grammatical properties with precision that is comparable to people's answers in the experiment. An important observation was that the neural network predicts low-probability words better than humans and predicts high-probability words worse than humans.

The second step in the study was to determine how experimental and corpus-based probabilities impact reading speed. To look into this, the researchers analysed data on eye movement in 96 people who were reading the same 144 sentences. The results showed that first, the higher the probability of guessing the part of speech, gender and number of nouns, as well as the tense of verbs, the faster the person read words with these features.

The researchers say that this proves that for languages with rich morphology, such as Russian, prediction is largely related to guessing words' grammatical properties.

Second, probabilities of grammatical features obtained from the neural network model explained reading speed as correctly as experimental probabilities. 'This means that for further studies, we will be able to use corpus-based probabilities from the language model without conducting new cloze task-based experiments,' commented Anastasiya Lopukhina https://www.hse.ru/en/staff/lopukhina, author of the paper and Research Fellow at the HSE Centre for Language and Brain.

Third, the probabilities of specific words received from the language model explained reading speed in a different way as compared to experiment-based probabilities. The authors assume that such a result may be related to different sources for corpus-based and experimental probabilities: corpus-based methods are better for low-probability words, and experimental ones are better for high-probability ones.

'Two things have been important for us in this work. First, we found out that reading native speakers of languages with rich morphology actively involve grammatical predicting,' Anastasiya Lopukhina said. 'Second, our colleagues, linguists and psychologists who study prediction got an opportunity to assess word probability with the use of language model: http://lm.ll-cl.org/. This will allow them to simplify the research process considerably'.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-16

Canadian researchers are the first to study how different patterns in the way older adults walk could more accurately diagnose different types of dementia and identify Alzheimer's disease.

A new study by a Canadian research team, led by London researchers from Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University, evaluated the walking patterns and brain function of 500 participants currently enrolled in clinical trials. Their findings are published today in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association.

"We have longstanding evidence showing that cognitive problems, such as poor memory and executive dysfunction, can ...

2021-02-16

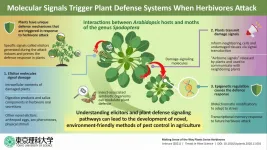

Nature has its way of maintaining balance. This statement rightly holds true for plants that are eaten by herbivores--insects or even mammals. Interestingly, these plants do not just silently allow themselves to be consumed and destroyed; in fact, they have evolved a defense system to warn them of predator attacks and potentially even ward them off. The defense systems arise as a result of inner and outer cellular signaling in the plants, as well as ecological cues. Plants have developed several ways of sensing damage; a lot of these involve the sensing of various "elicitor" molecules produced by either the predator ...

2021-02-16

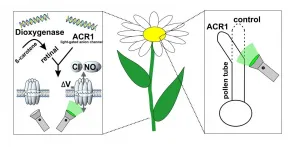

It is almost ten years since the scientific journal Science called optogenetics the "breakthrough of the decade". Put simply, the technique makes it possible to control the electrical activity of cells with pulses of light. With its help, scientists can gain new insights into the functioning of nerve cells, for example, and thus better understand neurological and psychiatric diseases such as depression and schizophrenia.

Established procedure on animal cells

In research on animal cells, optogenetics is now an established technique used in many fields. The picture is different in plant research: transferring the principle to plant cells and applying it widely has not been possible until now.

However, this has now changed: Scientists ...

2021-02-16

Individual variation in the shape and structure of the Achilles tendon may influence our susceptibility to injury later in life, says a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that studying individual Achilles tendon shape (or 'morphology') could help with identifying patients at risk of injury and designing new, potentially personalised approaches for treating and preventing Achilles tendinopathy and similar conditions.

The Achilles tendon is the tissue that links the calf muscles to the heel bone. It is fundamental to our movement and athletic ability. Its unique structure, which combines three smaller sub-tendons, increases the efficiency of our movement by allowing individual control from connected muscles. For this control to occur, the ...

2021-02-16

A drug that helps us to eat less could help the more than 650 million people around the world who live with obesity. One of the emerging drug candidates that interest researchers is the hormone GDF15 that, when given to rodents, lowers their appetite and body weight. New research from the University of Copenhagen finds that the body produces large amounts GDF15 during extended bouts of vigorous exercise, presumably as a physiological stress signal.

This finding highlights central differences between GDF15 given as a drug (pharmacology), and GDF15 released naturally in response to vigorous exercise (physiology). This is an important distinction ...

2021-02-16

From 2015 to 2019, public school districts in the United States invested nearly $5 billion to upgrade their Wi-Fi networks, according to EducationSuperHighway. However, in the age of COVID-19-mandated virtual learning, millions of K-12 students still lack the minimal connectivity at home for digital learning.

In a new study from the University of Notre Dame, researchers quantify how school district connectivity increases test scores, but underscore the dark side of technology -- increased behavior problems.

A $600,000 increase in annual internet access spending produces a financial gain of approximately $820,000 to $1.8 million, alongside losses from disciplinary problems totaling $25,800 to $53,440, according to new research from Yixing Chen, an ...

2021-02-16

Researchers at the University of Chicago, the University of Birmingham, and Bournemouth University have uncovered evidence that physical embodiment can occur without the sense of touch, thanks to a study involving two participants who lack the ability to feel touch. The research was published on Feb. 12 in END ...

2021-02-16

Coral reefs have thrived for millions of years in their shallow ocean water environments due to their unique partnerships with the algae that live in their tissues. Corals provide a safe haven and carbon dioxide while their algal symbionts provide them with food and oxygen produced from photosynthesis. Using the corals Orbicella annularis and Orbicella faveolate in the southern Caribbean, researchers at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology (IGB) have improved our ability to visualize and track these symbiotic interactions in the face of globally warming sea surface temperatures and ...

2021-02-16

In coming decades as coastal communities around the world are expected to encounter sea-level rise, the general expectation has been that people's migration toward the coast will slow or reverse in many places.

However, new research co-authored by Princeton University shows that migration to the coast could actually accelerate in some places despite sea-level change, contradicting current assumptions.

The research, published in Environmental Research Letters, uses a more complex behavioral decision-making model to look at Bangladesh, whose coastal zone is at high risk. They found job opportunities are most abundant in coastal cities across Bangladesh, attracting more ...

2021-02-16

It's no secret that the risk related to the coronavirus (COVID-19) increases with age, making older adults more vulnerable than younger people.

Less examined has been effects on pregnancy and birthing. According to a new study led by Sarah DeYoung, assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, and Michaela Mangum, a master's student in disaster science and management, the pandemic causes additional stress for people who were pregnant or gave birth during the pandemic. The stress was especially prevalent if the person ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Predicting words' grammatical properties helps us read faster

Such prediction can be successfully modelled by neural networks