(Press-News.org) The international research collaboration involving the research team led by evolutionary biologist Professor Axel Meyer at the University of Konstanz and researchers from China and Singapore was able to identify factors that led to the success of the seahorse from a developmental biology perspective: its quickness to adapt by, for example, repeatedly evolving spines in the skin and its fast genetic rates of evolution. The results will be published on 17 February 2021 in Nature Communications.

Seahorses of the genus Hippocampus emerged about 25 million years ago in the Indo-Pacific region from pipefish, their closest relatives. And while the latter usually swim fairly well, seahorses lack their pelvic and tail fins and evolved a prehensile tail instead that can be used, for example, to hold on to seaweed or corals. Early on, they split into two main groups. "One group stayed mainly in the same place, while the other spread all over the world", says Dr Ralf Schneider, who is now a postdoc-toral researcher at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, and participated in the study while working as a doctoral researcher in Axel Meyer's re-search team. In their original home waters of the Indo-Pacific, the remaining species diversified in a unique island environment, while the other group made its way into the Pacific Ocean via Africa, Europe and the Americas.

Travelling the world by raft

The particularly large amount of data collected for the study enabled the research team to create an especially reliable seahorse tree showing the relationships be-tween species and the global dispersal routes of the seahorse. Evolutionary biologist, Dr Schneider, says: "If you compare the relationships between the species to the ocean currents, you notice that seahorses were transported across the oceans". If, for example, they were carried out to sea during storms, they used their grasping tail to hold on to anything they could find, like a piece of algae or a tree trunk. These are places where the animals could survive for a long time. The currents often swept these "rafts" hundreds of kilometres across the ocean before they landed someplace where the seahorses could hop off and find a new home.

Since seahorses have been around for more than 25 million years, it was important to factor in that ocean currents have changed over time as tectonic plates have shift-ed. For example, about 15 million years ago, the Tethys Ocean was almost as large as today's Mediterranean Sea. On the west side, where the Strait of Gibraltar is lo-cated today, it connected to the Atlantic Ocean. On the east side, where the Arabian Peninsula is today, it led to the Indian Ocean.

Tectonic shifts change ocean currents

The researchers were able to underscore, for example, that the seahorses were able to colonize the Tethys Ocean via the Arabian Sea just before the tectonic plates shifted and sealed off the eastern connection. The resulting current flowing westward towards the Atlantic Ocean brought seahorses to North America. A few million years later, this western connection also closed and the entire Tethys Ocean dried out. Ralf Schneider: "Until now it was unclear whether seahorses in the Atlantic all traced their lineage to species from the Arabian Sea that had travelled south along the east coast of Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope and across the southern Atlantic Ocean to reach South America. We found out that a second lineage of seahorses had done just that, albeit later".

Since the research team gathered 20 animal samples from each habitat, it was also possible to measure the genetic variation between individuals. And this generally revealed: The greater the variation, the larger the population. "We can reconstruct the age of a variation based on its type. This makes it possible to calculate the size of the population at different points in time", the evolutionary biologist explains. This calculation reveals that the population that crossed the Atlantic Ocean to North America was very small, supporting the hypothesis that it have come from just a few animals brought there by the ocean's currents while holding on to a raft. The same data also showed that, even today, seahorses from Africa cross the southern Atlantic Ocean and introduce their genetic material into the South American population.

Fast and flexible adaptation

Seahorses not only spread around the world by travelling with the ocean currents, but they were also surprisingly good at settling in new habitats. Seahorses have greatly modified genomes and, throughout their evolution, they have lost many genes, emerged with new ones or gained duplicates. This means: Seahorses change very quickly in comparison to other fish. This is probably why different types of "bony spines" evolved quickly and independently of each other that protect seahorses from predation in some habitats.

Some of the genes have been identified that exhibit particular modifications for cer-tain species, but they are not the same for all species. Multiple fast and independent selections led to the development of spines, and although the same genes play a role in this development, different mutations were responsible. This shows that the slower, sessile seahorses were particularly able to adapt quickly to their environments. This is one of the main reasons the research team gives for seahorses being so successful in colonizing new habitats.

INFORMATION:

Key facts:

EMBARGOED UNTIL 17 FEBRUARY 2021, 11:00 (CET)

Original publication: Genome sequences of 21 seahorse species shed light on global dispersal routes and suggest convergent developmental mechanisms of unusual bony spines. Qiang Lin, Dr Chunyan Li, Melisa Olave, Yali Hou, Geng Qin, Ralf Schneider, Zexia Gao, Xiaolong Tu, Xin Wang, Dr Furong Qi, Alexander Nater, Andreas Kautt, Shiming Wan, Yanhong Zhang, Yali Liu, Dr Huixian Zhang, Bo Zhang, Hao Zhang, Meng Qu, Shuaishuai Liu, Zeyu Chen, Jia Zhong, He Zhang, Lingfeng Meng, Kai Wang, Jianping Yin, Liangmin Huang, Byrappa Venkatesh, Axel Meyer, Xuemei Lu, Qiang Lin: published on 17 February 2021 in Nature Communications. Doi 0.1038/s41467-021-21379-x

A research collaboration including the University of Konstanz examined the role of currents in the global dispersion of seahorses and found a particularly fast and independent convergent evolution of bony spines

Using the largest data set so far of almost 360 seahorse genomes, the team created a tree of seahorse species and reconstructed the emergence and dispersal of new species over the last 25 million years

Lead authors from the University of Konstanz are Dr Melisa Olave and Dr Ralf Schneider (now at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel). Other participating researchers from Konstanz include Dr Alexander Nater and Dr Andreas Kautt. Professor Axel Meyer and Professor Quiang Lin are the corresponding authors responsible for the study

Note to editors:

Images can be downloaded here:

https://cms.uni-konstanz.de/fileadmin/pi/fileserver/2021/wie_seepferdchen_3_c_ralf_schneider.jpeg

Copyright: Ralf Schneider

https://cms.uni-konstanz.de/fileadmin/pi/fileserver/2021/wie_seepferdchen_1_c_ralf_schneider.jpeg

Copyright: Ralf Schneider

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Though Ohio never formally enacted a so-called "heartbeat bill" banning abortions after six weeks of gestation, legislative and legal actions appear to have fueled beliefs that abortion is illegal in the state, a new study has found.

One in 10 Ohio women surveyed for the study thought abortion was prohibited. The percentage with that belief increased from 5% to 16% during the study period, corresponding to sustained activity to limit abortions from fall of 2018 through summer of 2019. The study appears in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Maria Gallo, the study's lead author and a professor of epidemiology at The Ohio State University, said repeated legislative attempts at extreme restrictions on abortion, the veto by ...

In Switzerland and other European countries, drug prices are regulated to ensure affordable access to drugs. In the last few years, many European countries have introduced rebate schemes for drugs. In most cases, however, the rebates negotiated with the manufacturer are confidential. This means that a country basically has two prices for a drug: an official, higher price and an actual, lower price. Price comparisons of drugs between countries is frequently based on the higher price. Switzerland too has introduced such rebates, which are often confidential, and plans to anchor this practice in the regulation. The Federal Social ...

Scientists have little understanding of the role fishes play in the global carbon cycle linked to climate change, but a Rutgers-led study found that carbon in feces, respiration and other excretions from fishes - roughly 1.65 billion tons annually - make up about 16 percent of the total carbon that sinks below the ocean's upper layers.

Better data on this key part of the Earth's biological pump will help scientists understand the impact of climate change and seafood harvesting on the role of fishes in carbon flux, according to the study - the first of its kind - in the journal Limnology and Oceanography. Carbon flux means the movement of carbon in the ocean, including from the surface to the deep sea - the focus of this study.

"Our study is the first to review ...

Robotic clothing that is entirely soft and could help people to move more easily is a step closer to reality thanks to the development of a new flexible and lightweight power system for soft robotics.

The discovery by a team at the University of Bristol could pave the way for wearable assist devices for people with disabilities and people suffering from age-related muscle degeneration. The study is published today [17 February] in Science Robotics.

Soft robots are made from compliant materials that can stretch and twist. These materials can be made into artificial muscles that contract when air is pumped into them. The softness of these muscles makes then suited to powering assistive clothing. Until now, however, these ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Scientists used accelerometers to track daily activity levels for a week in 89 adults with obesity or overweight and, in a series of tests, measured their ability to multitask and maintain their attention despite distractions. The study revealed that individuals who spent more sedentary time in bouts lasting 20 minutes or more were less able to overcome distractions.

Reported in the International Journal of Obesity, the research adds to the evidence linking sedentary behaviors and cognition, said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign kinesiology and ...

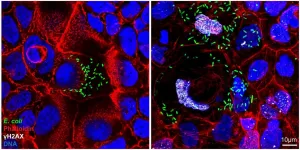

Escherichia coli bacteria are constitutive members of the human gut microbiota. However, some strains produce a genotoxin called colibactin, which is implicated in the development of colorectal cancer. While it has been shown that colibactin leaves very specific changes in the DNA of host cells that can be detected in colorectal cancer cells, such cancers take many years to develop, leaving the actual process by which a normal cell becomes cancerous obscure. The group of Thomas F. Meyer at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin together with their collaborators have now been able to "catch colibactin in the act" of inducing genetic changes that are characteristic of colorectal cancer cells and cause a transformed ...

Scientists at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health developed a method using a DNA biomarker to easily screen pregnant women for harmful prenatal environmental contaminants like air pollution linked to childhood illness and developmental disorders. This approach has the potential to prevent childhood developmental disorders and chronic illness through the early identification of children at risk.

While environmental factors--including air pollutants--have previously been associated with DNA markers, no studies to date have used DNA markers to flag environmental exposures in children. Study results are published ...

Women who received physical therapy after undergoing a cesarean section had significantly improved outcomes compared to those who did not according to a new study from University of Missouri Health Care.

"C-section is one of the most commonly performed inpatient procedures, and women who require C-section instead of a spontaneous vaginal delivery are at least twice as likely to suffer low back and pelvic pain," said study author Jennifer Stone, DPT, of MU Health Care's Mizzou Therapy Services. "Our goal was to evaluate the impact of comprehensive physical therapy on recovery following a cesarean birth."

Stone's study recruited 72 women who delivered by cesarean section ...

Preparing regular concrete scientists replaced ordinary water with water concentrate of bacteria Bacillus cohnii, which survived in the pores of cement stone. The cured concrete was tested for compression until it cracked, then researchers observed how the bacteria fixed the gaps restoring the strength of the concrete. The engineers of the Polytechnic Institute of Far Eastern Federal University (FEFU), together with colleagues from Russia, India, and Saudi Arabia, reported the results in Sustainability journal.

During the experiment, bacteria activated when gained access to oxygen and moisture, which occurred after the concrete cracked under the pressure of the setup. The "awakened" bacteria completely repaired fissures with a width ...

(Boston)--Veterans who experienced the combination of low depression, high social support and high psychological resilience as they left military service were most likely to report high well-being a year later.

Neither demographic and military characteristics nor trauma history emerged as strong predictors of veterans' well-being when considered in the context of other factors. Although most predictors were similar for women and men, depression was a stronger predictor of women's well-being.

Every year, more than 200,000 U.S. service members transition out of the military. Although most military veterans can be expected ...