Leopold proposed that predators keep herbivore populations in check to the benefit of an ecosystem's plant life. Remove one link in the food chain, and the effects cascade down its length. The idea of a trophic cascade has since become a mainstay in conservation ecology, with sea urchins as a prime example just off the California coast.

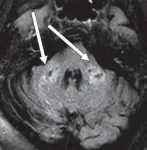

"Urchins play a key role in the kelp forest because they eat kelp," said Katrina Malakhoff(link is external), a doctoral student in UC Santa Barbara's Interdepartmental Graduate Program in Marine Science. "And there are times and places when urchins eat so much kelp that they actually end up removing it all and creating urchin barrens."

Scientists noticed that urchin populations seemed to explode after hunters decimated California's sea otters. The prickly critters went on to mow down entire kelp forests. Their conclusion: Predators like otters had kept the urchins in check. In Southern California, the otter's predatory role was thought to be filled by other species, particularly spiny lobster and sheephead fish.

But a new study by Malakhoff and her advisor, Robert Miller(link is external), suggests that the truth is much more nuanced. The researchers examined urchin populations inside and outside marine reserves, where protection from fishing should have enabled urchin predators to rebound and control their populations. But instead of finding fewer urchins, they found that one species was unaffected by the reserves, while the other flourished. Their work was supported by the National Science Foundation's Long-Term Ecological Research program, and results appear in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B [TK LINK].

Marine reserves cordon off areas of the ocean from fishing. They're often put in place to protect ecosystems by allowing species to recover, Malakhoff explained. In fact, California has a renowned network of marine protected areas along its coast, and many people hoped that the reserves could help control the region's two urchin species: the red sea urchin, which is fished for its roe, and the purple sea urchin, which isn't.

"We predicted that by protecting these areas we're increasing the number and density of urchin predators that will then control urchin populations and prevent them from overgrazing the kelp forest and turning it into an urchin barren," Malakhoff said. She sought to investigate this assumption, as well as the tendency of scientists and resource managers to lump the two species together and treat them as ecologically equivalent.

Malakhoff's project was made possible by the wealth of data ripe for analysis in the Channel Islands National Park Kelp Forest Monitoring Program, which has records stretching back to 1982. The data she used covers multiple sites from 13 years before, and roughly 15 years after, the establishment of marine reserves. As she examined figures on urchin populations, a peculiar trend began to emerge.

The reserves seemed to have no affect at all on unfished purple urchin populations. What's more, instead of decreasing in numbers, red urchins proliferated within the borders of some marine reserves. Their size, number and density increased once they no longer faced fishing pressures. Reserves also had no clear effect on giant kelp density.

"I was pretty surprised," Malakhoff said. "It contradicted what I expected to be happening in the kelp forest." If a rise in predation within the reserve influenced urchin populations, then both species should have decreased in number, and there ought to have been fewer small urchins, which provide an easier snack for predators.

"There's a simplistic picture that's been promulgated of kelp forests versus urchin barrens, and that predators are preventing this phase shift from happening," Miller said. The corollary is that, by restoring predator populations, reserves should allow the lush kelp forests to return.

Other studies have documented that the urchins' predators are thriving under the reserves' protection. The new results indicate that predation probably isn't the primary factor controlling urchin populations. For instance, larval dispersal and recruitment -- as well as the oceanographic regimes that affect them -- likely have greater effects on urchin populations, Miller said.

This study invites scientists to reconsider how common trophic cascades are, and whether marine reserves will always induce them. "Katrina's study adds to a growing body of evidence that suggests that trophic cascades are confined to a pretty narrow set of situations in the natural world," Miller said.

The two researchers acknowledge that some of their fellow scientists and resource managers might be reluctant to accept their conclusions. "The relationship between marine reserves and trophic cascades has approached paradigm status," Miller explained, "and it's always difficult to push back against a paradigm."

The study also calls into question the benefit to kelp forests of simply placing more area inside reserves. "One of the justifications that's been offered for expanding reserve coverage is saving kelp forests by increasing urchin predators," Miller said. "And this study suggests that this goal alone is not a good justification.

"I can see some controversy arising from this," he added, "but I think, as scientists, we have to maintain objectivity. We're fortunate that the Park Service and other monitoring programs collect the data we need to do this kind of analysis."

This doesn't mean that marine reserves are a bad idea, or that we should not expand them," he explained. "They clearly work very well for protecting fished species," Miller noted. "It's just that some of these popularly held ideas -- like that they'll cause trophic cascades to save the kelp -- might be less valid."

Marine protected areas may not be a panacea, but they do have their place. For one, they can serve as excellent natural experiments for scientists to investigate the effects of removing fishing from the equation. Stakeholders simply need to remember, the researchers said, that reserves are only one means of managing our oceans, and it's crucial to take advantage of all the strategies at their disposal.

Additionally, what scientists think will happen in a marine reserve may not always be what transpires, Malakhoff said, but that's not inherently a bad thing. "Just because we have more urchins inside the reserves doesn't necessarily mean we have less kelp," she pointed out, "because the story is complicated."

"These findings also highlight that we shouldn't necessarily adopt simplistic management approaches like smashing sea urchins to save kelp forests," Miller added.

Other factors influence how much kelp urchins eat, aside from their density. Urchin behavior also comes into play. Malakhoff is currently investigating how urchins digest different types of algae, and whether giant kelp truly is their preferred meal. This could shed light on the impact diet and other variables have on their grazing behavior.

"Sea urchins, they're sort of an enigma," said Miller. "Across the world, people are either trying to restore them or smash them based on a simple dichotomy: urchin good, urchin bad. But, like Katrina said, the truth may be somewhere in between."

INFORMATION: