Salk team reveals never-before-seen antibody binding, informing liver cancer, antibody design

Multi-institute collaboration uses X-ray crystallography and recombinant antibodies to uncover workings of an elusive molecule central to human health

2021-02-18

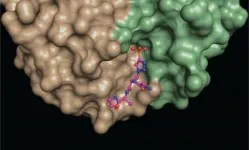

(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--(February 17, 2021) In structural biology, some molecules are so unusual they can only be captured with a unique set of tools. That's precisely how a multi-institutional research team led by Salk scientists defined how antibodies can recognize a compound called phosphohistidine--a highly unstable molecule that has been found to play a central role in some forms of cancer, such as liver and breast cancer and neuroblastoma.

These insights not only set up the researchers for more advanced studies on phosphohistidine and its potential role in cancer, but will also enable scientists to manipulate the shape and atomic makeup of the antibodies' binding sites in order to design ever more efficient antibodies in the future. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 5.

"We are excited that these new antibody structures reveal novel principles of antigen binding. Now we can redesign these antibodies and engineer their properties to make them more efficient," says Tony Hunter, Renato Dulbecco Chair and American Cancer Society Professor at Salk and the paper's senior author. "This work may also provide other scientists with phosphohistidine antibodies that better suit their research purposes."

Amino acids are joined together in precise sequences to form proteins, and several of them can undergo chemical transformations that can change the activity of the protein for better or worse. One such transformation is a process called phosphorylation, when a compound called phosphate is added to an amino acid, changing its shape and charge. Previously, Hunter showed that phosphorylation on the amino acid tyrosine can drive cancer progression, a discovery that led to numerous anticancer drugs. More recently, Hunter turned his attention to phosphorylation of the amino acid histidine (which creates phosphohistidine), suspecting that the process might also play a role in human disease.

Hunter developed a suite of antibodies able to bind to phosphohistidine in proteins, and used chemically stabilized phosphohistidine analogues to develop a series of monoclonal antibodies that could recognize these forms. The next step was to understand exactly how the antibodies are able to bind to phosphohistidine. This led Hunter to collaborate with Ian Wilson, the Hansen Professor of Structural Biology at the Scripps Research Institute and a world-renowned expert in using protein crystallography to define antibody structures, to study the structures of the phosphohistidine antibodies.

"My long-term colleague Tony and I have been collaborating on this project for the past seven years," says Wilson. "We have obtained new insights into how antibodies can evolve to recognize phosphates linked to proteins, which is very satisfying."

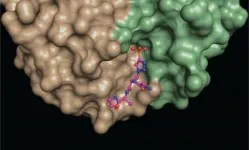

To find out how phosphohistidine is recognized, they needed to image their antibodies in the act of binding the phosphohistidine, and so formed crystals between each antibody bound to a phosphohistidine peptide.

"To understand the molecular interactions between the antibodies and phosphohistidine, we needed to look at them in great detail," says first author Rajasree Kalagiri, a Salk postdoctoral researcher and expert in X-ray crystallography. "Once we got the antibodies to form crystals, we bombarded those crystals with X-rays to obtain a diffraction pattern. We then applied methods that transform the diffraction pattern into a three-dimensional electron density map, which was then used to discern the atomic structure of the antibodies."

The two types of antibody crystal structures solved by the team revealed exactly how different amino acids are arranged around the phosphohistidine to bind it tightly. Their five structures more than double the number of phospho-specific antibody structures previously reported, and provide insights into how antibodies recognize both the phosphate and the linked histidine. They also reveal at a structural level how the two types of antibody recognize different forms of phosphohistidine, and this will allow the scientists to engineer improved antibodies in the future.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study were Jill Meisenhelder and Stephen R. Fuhs of Salk; Robyn Stanfield of the Scripps Research Institute; and James J. La Clair of the University of California San Diego.

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at The Scripps Research Institute.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Every cure has a starting point. The Salk Institute embodies Jonas Salk's mission to dare to make dreams into reality. Its internationally renowned and award-winning scientists explore the very foundations of life, seeking new understandings in neuroscience, genetics, immunology, plant biology and more. The Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature and fearless in the face of any challenge. Be it cancer or Alzheimer's, aging or diabetes, Salk is where cures begin. Learn more at: salk.edu.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-17

Deprive a mountain range of its wolves, and soon the burgeoning deer population will strip its slopes bare. "I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer," wrote ecologist Aldo Leopold in his landmark 1949 title "A Sand County Almanac."

Leopold proposed that predators keep herbivore populations in check to the benefit of an ecosystem's plant life. Remove one link in the food chain, and the effects cascade down its length. The idea of a trophic cascade has since become a mainstay in conservation ecology, with sea urchins as a prime example just off the California ...

2021-02-17

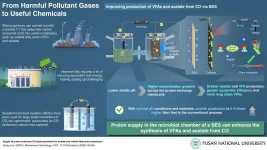

Rapid global urbanization has dramatically changed the face of our planet, polluting our atmosphere with greenhouse gases and causing global warming. It is the need of the hour to control our activities and find more sustainable alternatives to preserve what remains of our planet for the generations to come.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) make up a large proportion of industrial flue gases. Recent research has shown that certain microorganisms are capable of metabolizing these gases into useful by-products. Thus, attempts are now being directed to ...

2021-02-17

BOSTON - Delirium, a common syndrome among older adults, particularly in those who have recently undergone surgery, critically ill patients in the ICU, and in older patients with multiple health issues, is a form of acute confusion that is characterized by poor attention, disorientation, impaired memory, delusions, and abrupt changes in mood and behavior. Moreover, patients who experience delirium are at increased risk of long term cognitive decline. Recently, clinicians and scientists have recognized that delirium is one of the first signs of COVID-19 infection in older patients and that it occurs frequently in patients with severe COVID-19 disease.

In a new study led by an interdisciplinary team of gerontologists, geriatricians, precision medicine ...

2021-02-17

Dogs are generally considered the first domesticated animal, while its ancestor is generally considered to be the wolf, but where the Australian dingo fits into this framework is still debated, according to a retired Penn State anthropologist.

"Indigenous Australians understood that there was something different about the dingoes and the colonial dogs," said Pat Shipman, retired adjunct professor of anthropology, Penn State. "They really are, I think, different animals. They react differently to humans. A lot of genetic and behavioral work has been done with wolves, dogs and dingoes. Dingoes come out somewhere ...

2021-02-17

Scientists from the Skoltech Center for Computational and Data-Intensive Science and Engineering (CDISE) and the Skoltech Digital Agriculture Laboratory and their collaborators from the German Aerospace Center (DLR) have developed an artificial intelligence (AI) system that enables processing images from autonomous greenhouses, monitoring plant growth and automating the cultivation process. Their research was published in the journal IEEE Sensors.

Modern technology has long become a fixture in all spheres of human life on Earth. Reaching out to other planets is a new challenge for humankind. Since greenhouses are likely to be the only source ...

2021-02-17

BOSTON - Use of a cosmetic laser invented at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) may improve the effectiveness of certain anti-tumor therapies and extend their use to more diverse forms of cancer. The strategy was tested and validated in mice, as described in a study published in Science Translational Medicine.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are important medications that boost the immune system's response against various cancers, but only certain patients seem to benefit from the drugs. The cancer cells of these patients often have multiple mutations that can be recognized as foreign by the immune system, thereby inducing an inflammatory response.

In an attempt to expand the benefits of immune checkpoint inhibitors ...

2021-02-17

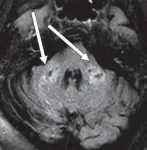

Leesburg, VA, February 17, 2021--According to an open-access article in ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), COVID-19-related disseminated leukoencephalopathy (CRDL) represents an important--albeit uncommon--differential consideration in patients with neurologic manifestations of coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

"Increasingly," wrote Colbey W. Freeman and colleagues from the University of Pennsylvania, "effects of COVID-19 on the brain are being reported, including acute necrotizing encephalopathy, infarcts, microhemorrhage, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and leukoencephalopathy."

Among the 2,820 patients with COVID-19 admitted to the authors' institution between ...

2021-02-17

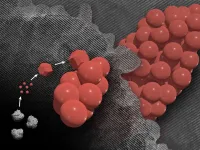

When materials reach extremely small size scales, strange things begin to happen. One of those phenomena is the formation of mesocrystals.

Despite being composed of separate individual crystals, mesocrystals come together to form a larger, fused structure that behaves as a pure, single crystal. However, these processes happen at scales far too small for the human eye to see and their creation is extremely challenging to observe.

Because of these challenges, scientists had not been able to confirm exactly how mesocrystals form.

Now new research by a Pacific ...

2021-02-17

A considerable portion of the efforts to realize a sustainable world has gone into developing hydrogen fuel cells so that a hydrogen economy can be achieved. Fuel cells have distinctive advantages: high energy-conversion efficiencies (up to 70%) and a clean by-product, water. In the past decade, anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFC), which convert chemical energy to electrical energy via the transport of negatively charged ions (anions) through a membrane, have received attention due to their low-cost and relative environment friendliness compared ...

2021-02-17

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers who focus on fat know that some adipose tissue is more prone to inflammation-related comorbidities than others, but the reasons why are not well understood. Thanks to a new analytical technique, scientists are getting a clearer view of the microenvironments found within adipose tissue associated with obesity. This advance may illuminate why some adipose tissues are more prone to inflammation - leading to diseases like type 2 diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disorders - and help direct future drug therapies to treat obesity.

In a new study, University of Illinois ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Salk team reveals never-before-seen antibody binding, informing liver cancer, antibody design

Multi-institute collaboration uses X-ray crystallography and recombinant antibodies to uncover workings of an elusive molecule central to human health