Rapid evolution may help species adapt to climate change and competition

2021-02-22

(Press-News.org) VANCOUVER, Wash. - Loss of biodiversity in the face of climate change is a growing worldwide concern. Another major factor driving the loss of biodiversity is the establishment of invasive species, which often displace native species. A new study shows that species can adapt rapidly to an invader and that this evolutionary change can affect how they deal with a stressful climate.

"Our results demonstrate that interactions with competitors, including invasive species, can shape a species' evolution in response to climatic change," said co-author Seth Rudman, a WSU Vancouver adjunct professor who will join the faculty as an assistant professor of biological sciences in the fall.

Results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences as "Competitive history shapes rapid evolution in a seasonal climate."

Scientists have increasingly recognized that evolution is not necessarily slow and often occurs quickly enough to be observed in real time. These rapid evolutionary changes can have major consequences for things like species' persistence and responses to climatic change. The investigators chose to examine this topic in fruit flies, which reproduce quickly, allowing change to be observed over several generations in a matter of months. The team focused on two species: one naturalized in North American orchards (Drosophila melanogaster) and one that has recently started to invade North America (Zaprionus indianus).

The experiment first tested whether the naturalized species can evolve rapidly in response to exposure to the invasive species over the summer, then tested how adaptation in the summer affects the naturalized species' ability to deal with and adapt to the colder fall conditions.

"A cool thing about the way we conducted this study is that while most experiments that look at rapid evolution use controlled lab systems, we used an outdoor experimental orchard that mimics the natural habitat of our focal species," said Tess Grainger of the Biodiversity Centre at the University of British Columbia and the lead author on the paper. "This gives our experiment a sense of realism and makes our findings more applicable to understanding natural systems."

Over the course of just a few months, the naturalized species adapted to the presence of the invasive species. This rapid evolution then affected how the flies evolved when the cold weather hit. Flies that had been previously exposed to the invasive species evolved in the fall to be larger, lay fewer eggs and develop faster than flies that had never been exposed.

The study marks the beginning of research that may ultimately hold implications for other threatened species that are more difficult to study. "In the era of global environmental change in which species are increasingly faced with new climates and new competitors, these dynamics are becoming essential to understand and predict," Grainger said.

Rudman summarized the next big question: "As biodiversity changes, as climate changes and invaders become more common, what can rapid evolution do to affect outcomes of those things over the next century or two? It may be that rapid evolution will help biodiversity be maintained in the face of these changes."

In addition to Rudman and Grainger, the paper's co-authors are Jonathan M. Levine, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department, Princeton University (where Grainger was a postdoctoral fellow); and Paul Schmidt, Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania (where Rudman was a postdoctoral fellow). The research was conducted in an outdoor field site near the University of Pennsylvania.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-22

BEER-SHEVA, Israel...February 22, 2021 - A new study by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) researchers resulted in a nearly unanimous response: driving is "absolutely impossible" without music.

"To young drivers 18-29, music in the car isn't just entertainment, it's part of their autosphere whether they're alone or not," says Prof. Warren Brodsky, director of the BGU Music Science Lab in the Department of the Arts. "They are so used to constant stimulation and absorbing great amounts of information throughout the day, that they don't question how the type of tunes they play might affect concentration, induce aggressive behavior, or cause them to miscalculate risky situations."

"As the fastest growing research university in Israel, BGU provides studies that give us ...

2021-02-22

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. - Automotive recalls are occurring at record levels, but seem to be announced after inexplicable delays. A research study of 48 years of auto recalls announced in the United States finds carmakers frequently wait to make their announcements until after a competitor issues a recall - even if it is unrelated to similar defects.

This suggests that recall announcements may not be triggered solely by individual firms' product quality defect awareness or concern for the public interest, but may also be influenced by competitor recalls, a phenomenon that no prior research had investigated.

Researchers analyzed 3,117 auto recalls over a 48-year period -- from 1966 to 2013 -- using ...

2021-02-22

In a world as diverse as our own, the journey towards a sustainable future will look different depending on where in the world we live, according to a recent paper published in One Earth and led by McGill University, with researchers from the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

"There are many regional pathways to a more sustainable future, but our lack of understanding about how these complex and sometimes contradictory pathways interact (and in particular when they synergize or compete with one another) limits our ability to choose the 'best' ones," says Elena Bennett, a professor in the Department of Natural ...

2021-02-22

Eating a low quality diet, high in foods and food components associated with chronic inflammation, during pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of obesity and excess body fat in children, especially during late-childhood. The findings are published the open access journal BMC Medicine.

Researchers from University College Dublin, Ireland found that children of mothers who ate a higher quality diet, low in inflammation-associated foods, during pregnancy had a lower risk of obesity and lower body fat levels in late-childhood than children whose mothers ate a lower quality diet, ...

2021-02-22

Researchers have mapped an underlying "psychological signature" for people who are predisposed to holding extreme social, political or religious attitudes, and support violence in the name of ideology.

A new study suggests that a particular mix of personality traits and unconscious cognition - the ways our brains take in basic information - is a strong predictor for extremist views across a range of beliefs, including nationalism and religious fervour.

These mental characteristics include poorer working memory and slower "perceptual strategies" - the unconscious processing of changing stimuli, such as shape and colour - as well as tendencies towards impulsivity and sensation seeking.

This combination of cognitive and ...

2021-02-22

Researchers have called on European policymakers to make adequate resources available to tackle pancreatic cancer, a disease that is almost invariably fatal and where little progress has been made over the past 40 years.

In the latest predictions for cancer deaths in the EU and UK for 2021, published in the leading cancer journal Annals of Oncology [1] today (Monday), researchers led by Carlo La Vecchia (MD), a professor at the University of Milan (Italy), say that pancreatic death rates are predicted to remain approximately stable for men, but continue to rise in women in most EU countries.

The researchers predict that ...

2021-02-22

Home gardens are by far the biggest source of food for pollinating insects, including bees and wasps, in cities and towns, according to new research.

The study, led by the University of Bristol and published today in the Journal of Ecology, measured for the first time how much nectar is produced in urban areas and discovered residential gardens accounted for the vast majority - some 85 per cent on average.

Results showed three gardens generated daily on average around a teaspoon of Nature's ambrosia, the unique sugar-rich liquid found in flowers which pollinators drink for energy. While a teaspoon ...

2021-02-22

Muscle is the largest organ that accounts for 40% of body mass and plays an essential role in maintaining our lives. Muscle tissue is notable for its unique ability for spontaneous regeneration. However, in serious injuries such as those sustained in car accidents or tumor resection which results in a volumetric muscle loss (VML), the muscle's ability to recover is greatly diminished. Currently, VML treatments comprise surgical interventions with autologous muscle flaps or grafts accompanied by physical therapy. However, surgical procedures often lead to a reduced muscular function, and in some cases result in a complete graft failure. Thus, there is a demand for additional therapeutic options to improve muscle loss recovery.

A promising strategy to improve ...

2021-02-21

Coral within the family Acropora are fast growers and thus important for reef growth, island formation, and coastal protection but, due to global environmental pressures, are in decline

A species within this family has three different color morphs - brown, yellow-green, and purple, which appear to respond differently to high temperatures

Researchers looked at the different proteins expressed by the different color morphs, to see whether these were related to their resilience to a changing environment

The green variant was found to maintain high levels of green fluorescent proteins during summer heatwaves and was less likely to bleach than the other two morphs

This suggest that resistance to thermal stress is influenced by a coral's underlying genetics, ...

2021-02-20

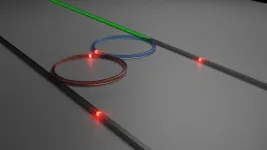

Periodic pulses of light forming a comb in the frequency domain are

widely used for sensing and ranging. The key to the miniaturisation of

this technology towards chip-integrated solutions is the generation of

dissipative solitons in ring-shaped microresonators. Dissipative solitons

are stable pulses circulating around the circumference of a nonlinear

resonator.

Since their first demonstration, the process of dissipative soliton

formation has been extensively studied and today it is rather

considered as textbook knowledge. Several directions of further

development are ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Rapid evolution may help species adapt to climate change and competition