INFORMATION:

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

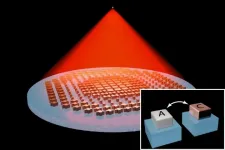

New "metalens" shifts focus without tilting or moving

The design may enable miniature zoom lenses for drones, cellphones, or night-vision goggles.

2021-02-22

(Press-News.org) Polished glass has been at the center of imaging systems for centuries. Their precise curvature enables lenses to focus light and produce sharp images, whether the object in view is a single cell, the page of a book, or a far-off galaxy.

Changing focus to see clearly at all these scales typically requires physically moving a lens, by tilting, sliding, or otherwise shifting the lens, usually with the help of mechanical parts that add to the bulk of microscopes and telescopes.

Now MIT engineers have fabricated a tunable "metalens" that can focus on objects at multiple depths, without changes to its physical position or shape. The lens is made not of solid glass but of a transparent "phase-changing" material that, after heating, can rearrange its atomic structure and thereby change the way the material interacts with light.

The researchers etched the material's surface with tiny, precisely patterned structures that work together as a "metasurface" to refract or reflect light in unique ways. As the material's property changes, the optical function of the metasurface varies accordingly. In this case, when the material is at room temperature, the metasurface focuses light to generate a sharp image of an object at a certain distance away. After the material is heated, its atomic structure changes, and in response, the metasurface redirects light to focus on a more distant object.

In this way, the new active "metalens" can tune its focus without the need for bulky mechanical elements. The novel design, which currently images within the infrared band, may enable more nimble optical devices, such as miniature heat scopes for drones, ultracompact thermal cameras for cellphones, and low-profile night-vision goggles.

"Our result shows that our ultrathin tunable lens, without moving parts, can achieve aberration-free imaging of overlapping objects positioned at different depths, rivaling traditional, bulky optical systems," says Tian Gu, a research scientist in MIT's Materials Research Laboratory.

Gu and his colleagues have published their results today in the journal Nature Communications. His co-authors include Juejun Hu, Mikhail Shalaginov, Yifei Zhang, Fan Yang, Peter Su, Carlos Rios, Qingyang Du, and Anuradha Agarwal at MIT; Vladimir Liberman, Jeffrey Chou, and Christopher Roberts of MIT Lincoln Laboratory; and collaborators at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, the University of Central Florida, and Lockheed Martin Corporation.

A material tweak

The new lens is made of a phase-changing material that the team fabricated by tweaking a material commonly used in rewritable CDs and DVDs. Called GST, it comprises germanium, antimony, and tellurium, and its internal structure changes when heated with laser pulses. This allows the material to switch between transparent and opaque states -- the mechanism that enables data stored in CDs to be written, wiped away, and rewritten.

Earlier this year, the researchers reported adding another element, selenium, to GST to make a new phase-changing material: GSST. When they heated the new material, its atomic structure shifted from an amorphous, random tangle of atoms to a more ordered, crystalline structure. This phase shift also changed the way infrared light traveled through the material, affecting refracting power but with minimal impact on transparency.

The team wondered whether GSST's switching ability could be tailored to direct and focus light at specific points depending on its phase. The material then could serve as an active lens, without the need for mechanical parts to shift its focus.

"In general when one makes an optical device, it's very challenging to tune its characteristics postfabrication," Shalaginov says. "That's why having this kind of platform is like a holy grail for optical engineers, that allows [the metalens] to switch focus efficiently and over a large range."

In the hot seat

In conventional lenses, glass is precisely curved so that incoming light beam refracts off the lens at various angles, converging at a point a certain distance away, known as the lens' focal length. The lenses can then produce a sharp image of any objects at that particular distance. To image objects at a different depth, the lens must physically be moved.

Rather than relying on a material's fixed curvature to direct light, the researchers looked to modify GSST-based metalens in a way that the focal length changes with the material's phase.

In their new study, they fabricated a 1-micron-thick layer of GSST and created a "metasurface" by etching the GSST layer into microscopic structures of various shapes that refract light in different ways.

"It's a sophisticated process to build the metasurface that switches between different functionalities, and requires judicious engineering of what kind of shapes and patterns to use," Gu says. "By knowing how the material will behave, we can design a specific pattern which will focus at one point in the amorphous state, and change to another point in the crystalline phase."

They tested the new metalens by placing it on a stage and illuminating it with a laser beam tuned to the infrared band of light. At certain distances in front of the lens, they placed transparent objects composed of double-sided patterns of horizontal and vertical bars, known as resolution charts, that are typically used to test optical systems.

The lens, in its initial, amorphous state, produced a sharp image of the first pattern. The team then heated the lens to transform the material to a crystalline phase. After the transition, and with the heating source removed, the lens produced an equally sharp image, this time of the second, farther set of bars.

"We demonstrate imaging at two different depths, without any mechanical movement," Shalaginov says.

The experiments show that a metalens can actively change focus without any mechanical motions. The researchers say that a metalens could be potentially fabricated with integrated microheaters to quickly heat the material with short millisecond pulses. By varying the heating conditions, they can also tune to other material's intermediate states, enabling continuous focal tuning.

"It's like cooking a steak -- one starts from a raw steak, and can go up to well done, or could do medium rare, and anything else in between," Shalaginov says. "In the future this unique platform will allow us to arbitrarily control the focal length of the metalens."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Air pollution puts children at higher risk of disease in adulthood

2021-02-22

Children exposed to air pollution, such as wildfire smoke and car exhaust, for as little as one day may be doomed to higher rates of heart disease and other ailments in adulthood, according to a new Stanford-led study. The analysis, published in Nature Scientific Reports, is the first of its kind to investigate air pollution's effects at the single cell level and to simultaneously focus on both the cardiovascular and immune systems in children. It confirms previous research that bad air can alter gene regulation in a way that may impact long-term health - a finding that could change the way medical experts and parents think about the air children ...

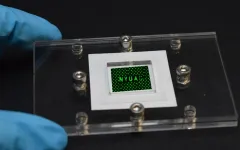

NYUAD researchers develop high throughput paper-based arrays of 3D tumor models

2021-02-22

Abu Dhabi, UAE, February 22: By engineering common filter papers, similar to coffee filters, a team of NYU Abu Dhabi researchers have created high throughput arrays of miniaturized 3D tumor models to replicate key aspects of tumor physiology, which are absent in traditional drug testing platforms. With the new paper-based technology, the formed tumor models can be safely cryopreserved and stored for prolonged periods for on-demand drug testing use. These cryopreservable tumor models could provide the pharmaceutical industry with an easy and low cost method for investigating the outcomes of drug efficacy, potentially bolstering personalized ...

Parents of children with cancer have additional worries during COVID

2021-02-22

DURHAM, N.C. - The COVID-19 pandemic has heaped additional financial strains, childcare complications and other problems on already-burdened caregivers of children diagnosed with cancer, according to a study from researchers at Duke Health and other institutions.

Surveying 360 parents and caregivers of children currently in treatment or still being monitored for cancer, the researchers found that half had to cancel or delay appointments, 77% reported increased feelings of anxiety and of those who had lost jobs or wages, 11% struggled to pay for basic needs.

The survey findings appear online this month in the journal Pediatric Blood & Cancer.

"Parents and caregivers ...

Study could explain tuberculosis bacteria paradox

2021-02-22

HOUSTON - (Feb. 22, 2021) -Tuberculosis bacteria have evolved to remember stressful encounters and react quickly to future stress, according to a study by computational bioengineers at Rice University and infectious disease experts at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School (NJMS).

Published online in the open-access journal mSystems, the research identifies a genetic mechanism that allows the TB-causing bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, to respond to stress rapidly and in manner that is "history-dependent," said corresponding author Oleg Igoshin, a professor of bioengineering at Rice.

Researchers have long suspected that the ability of TB bacteria to remain dormant, sometimes for decades, ...

Tricking the novel coronavirus with a fake "handshake"

2021-02-22

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Fool the novel coronavirus once and it can't cause infection of cells, new research suggests.

Scientists have developed protein fragments - called peptides - that fit snugly into a groove on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein that it would normally use to access a host cell. These peptides effectively trick the virus into "shaking hands" with a replica rather than with the actual protein on a cell's surface that lets the virus in.

Previous research has determined that the novel coronavirus binds to a receptor protein on a target cell's surface called ACE2. This receptor is located on certain types of human cells in the lung and nasal cavity, providing SARS-CoV-2 many access points to infect the body.

For this work, Ohio State University scientists designed and tested peptides ...

Yale scientists repair injured spinal cord using patients' own stem cells

2021-02-22

Intravenous injection of bone marrow derived stem cells (MSCs) in patients with spinal cord injuries led to significant improvement in motor functions, researchers from Yale University and Japan report Feb. 18 in the Journal of Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery.

For more than half of the patients, substantial improvements in key functions -- such as ability to walk, or to use their hands -- were observed within weeks of stem cell injection, the researchers report. No substantial side effects were reported.

The patients had sustained, non-penetrating spinal cord injuries, in many cases from falls or minor trauma, several weeks prior to implantation of the stem cells. Their symptoms ...

'Jumping genes' repeatedly form new genes over evolution

2021-02-22

ITHACA, N.Y. - In the same way that Lego pieces can be arranged in new ways to build a variety of structures, genetic elements can be mixed and matched to create new genes, according to new research.

A long-proposed mechanism for creating genes, called exon shuffling, works by shuffling functional blocks of DNA sequences into new genes that express proteins.

A study, "Recurrent Evolution of Vertebrate Transcription Factors by Transposase Capture," published Feb. 19 in Science, investigates how genetic elements called transposons, or "jumping genes," are added into the mix during evolution to assemble new genes through exon shuffling.

Transposons, first discovered in the 1940s by Cornell alum and Nobel Prize-winner Barbara McClintock '23, M.A. '25, Ph.D. '27, are ...

Antibiotic tolerance study paves way for new treatments

2021-02-22

ITHACA, N.Y. - A new study identifies a mechanism that makes bacteria tolerant to penicillin and related antibiotics, findings that could lead to new therapies that boost the effectiveness of these treatments.

Antibiotic tolerance is the ability of bacteria to survive exposure to antibiotics, in contrast to antibiotic resistance, when bacteria actually grow in the presence of antibiotics. Tolerant bacteria can lead to infections that persist after treatment and may develop into resistance over time.

The study in mice, "A Multifaceted Cellular Damage Repair and Prevention Pathway Promotes ...

Focus on the positive to improve classroom behavior

2021-02-22

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- When teachers encounter disruptive or noncompliant students in the classroom, they typically respond by focusing on the negative behavior. However, new research from the University of Missouri found that offering students more positive encouragement not only reduces disruptive classroom behavior, but can improve students' academic and social outcomes.

"As educators, we often focus on communicating what we don't want our students to be doing in class, but we have found that just doesn't work," said Keith Herman, a professor in the University of Missouri College of Education. "Instead, we need to be setting clear expectations ...

Sleep is vital to associating emotion with memory, according to U-M study

2021-02-22

When you slip into sleep, it's easy to imagine that your brain shuts down, but University of Michigan research suggests that groups of neurons activated during prior learning keep humming, tattooing memories into your brain.

U-M researchers have been studying how memories associated with a specific sensory event are formed and stored in mice. In a study conducted prior to the coronavirus pandemic and recently published in Nature Communications, the researchers examined how a fearful memory formed in relation to a specific visual stimulus.

They found that not only did the neurons activated by the visual ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] New "metalens" shifts focus without tilting or movingThe design may enable miniature zoom lenses for drones, cellphones, or night-vision goggles.