Fat cells may influence how the body reacts to heart failure, study shows

Promising results in mice open door to new areas of research in treating patients with heart failure.

2021-02-23

(Press-News.org) University of Alberta researchers have found that limiting the amount of fat the body releases into the bloodstream from fat cells during heart failure could help improve outcomes for patients.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Physiology, Jason Dyck, professor of pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry and director of the U of A's Cardiovascular Research Centre, found that mice with heart failure that were treated with a drug blocking the release of fat into the bloodstream from fat cells saw less inflammation in the heart and throughout the body, and had better outcomes than a control group.

"Many people believe that, by definition, heart failure is only a condition of the heart. But it's much broader and multiple organs are affected by it," said Dyck, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Molecular Medicine and is a member of the Alberta Diabetes Institute and the Women and Children's Health Research Institute. "What we've shown in mice is that if you can target fat cells with a drug and limit their ability to release stored fat during heart failure, you can protect the heart and improve cardiac function.

"I think it really opens the door for other avenues of investigation and therapies for treating heart failure," Dyck noted.

During times of stress, such as heart failure, the body releases stress hormones, such as epinephrine and norepinephrine, to help the heart compensate. But because the heart can't function any better--and is in fact damaged further by being forced to pump faster--the body releases more stress hormones and the process cascades, with heart function continuing to decline. This is why a common treatment for heart failure is beta-blocker drugs, which are designed to block the effects of stress hormones on the heart.

The release of stress hormones also triggers the release of fat from its storage deposits in fat cells into the bloodstream to provide extra energy to the body, a process called lipolysis. Dyck's team found that during heart failure, the fat cells in mice were also becoming inflamed throughout the body, mobilizing and releasing fat faster than normal and causing inflammation in the heart and rest of the body. This inflammation put additional stress on the heart, adding to the cascade effect, increasing damage and reducing heart function.

"Our research began by looking at how the function of one organ can affect other organs, so I thought it was very fascinating to find that a fat cell can influence cardiac function in heart failure," Dyck said. "Fortunately, we had a drug that could inhibit fat mobilization from fat cells in mice, which actually protected the hearts from damage caused by inflammation."

Dyck points out that although his results are promising, more work is needed to better understand the exact mechanisms at play in the process and develop a drug that could work in humans.

"This work is a proof-of-concept showing that abnormal fat-cell function contributes to worsening heart failure, and now we're working on understanding the mechanisms of how the drug works to limit lipolysis better," he said. "Once we get that, that's the launchpad for making sure it's safe and efficacious, then advancing it to our chemists, and then maybe some early trials in humans."

Dyck said the findings--and a better understanding of how organ functions affect other organs--could be used to develop new approaches to several other diseases.

"We know that people have high rates of lipolysis when they have heart failure, so I presume this approach would benefit all types of heart failure," he said. "But if you consider that inflammation is associated with a wide variety of different diseases, like cancer, diabetes or other forms of heart disease, then this approach could have a much wider benefit."

INFORMATION:

Dyck's research was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-23

New Orleans, LA - An LSU Health New Orleans School of Public Health study reports a positive association between social vulnerability and COVID-19 incidence at the census tract level and recommends that more resources be allocated to socially vulnerable populations to reduce the incidence of COVID-19. The findings are published in Frontiers in Public Health, available END ...

2021-02-23

Gay men are more likely than lesbian women to face stigma and avoidant prejudice from their heterosexual peers due to the sound of their voice, a new study in the British Journal of Social Psychology reports. Researchers also found that gay men who believe they sound gay anticipate stigma and are more vigilant regarding the reactions of others.

During this unique study researchers from the University of Surrey investigated the role of essentialist beliefs -- the view that every person has a set of attributes that provide an insight into their identity -- of heterosexual, lesbian ...

2021-02-23

In Wonderland, Alice drank a potion to shrink herself. In nature, some animal species shrink to escape the attention of human hunters, a process that takes from decades to millennia. To begin to understand the genetics of shrinking, scientists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama successfully extracted DNA from marine shells. Their new technique will not only shed light on how animals from lizards to lemurs shrink, it will reveal many other stories hidden in shells.

"Humans are unique as predators," said Alexis Sullivan, doctoral student at Penn ...

2021-02-23

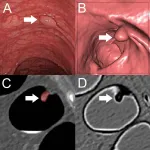

OAK BROOK, Ill. - A machine learning algorithm helps accurately differentiate benign and premalignant colorectal polyps on CT colonography scans, according to a study published in the journal Radiology.

Colorectal cancer is among the three most common causes of cancer-related death among men and women in industrialized countries. Most types of colorectal cancer originate from adenomatous polyps--gland-like growths on the mucous membrane lining the large intestine--that develop over several years. Early detection and removal of these precancerous polyps can reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

During the last two decades, CT colonography emerged as a noninvasive ...

2021-02-23

Peer review/observational study/people

In patients with severe COVID-19, the innate immune system overreacts. This overreaction may underlie the formation of blood clots (thrombi) and deterioration in oxygen saturation that affect the patients. This is shown in an Uppsala University study published in the journal Frontiers in Immunology.

Blood contains numerous proteins that constitute the body's primary barrier, by both recognising and destroying microorganisms, including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). These proteins are part of the intravascular innate immune system (IIIS), which consists of certain white blood cells, platelets and what are known as the cascade systems of the blood.

Only 5 ...

2021-02-23

Glaciers in West Antarctica are moving more quickly from land into the ocean, contributing to rising global sea levels. A 25-year record of satellite observations has been used to show widespread increases in ice speed across the Getz sector for the first time, with some ice accelerating into the ocean by nearly 50%.

The new study, led by the University of Leeds, reports that 14 glaciers in the Getz region are thinning and flowing more quickly into the ocean. Between 1994 and 2018, 315 gigatonnes of ice has been lost, adding 0.9 mm to global mean sea level - equivalent to 126 million Olympic swimming pools of water.

The results published today (19/02/2021) in the journal Nature Communications show that, on average, ...

2021-02-23

A radiotherapy technique which 'paints' tumours by targeting them precisely, and avoiding healthy tissue, has been devised in research led by the University of Strathclyde.

Researchers used a magnetic lens to focus a Very High Electron Energy (VHEE) beam to a zone of a few millimetres. Concentrating the radiation into a small volume of high dose will enable it to be rapidly scanned across a tumour, while controlling its intensity.

It is being proposed as an alternative to other forms of radiotherapy, which can risk non-tumorous tissue becoming overexposed to radiation.

The researchers are planning further investigation, with the use of a purpose-built device.

The study ...

2021-02-23

During glacial periods, the sea level falls, because vast quantities of water are stored in the massive inland glaciers. To date, however, computer models have been unable to reconcile sea-level height with the thickness of the glaciers. Using innovative new calculations, a team of climate researchers led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now managed to explain this discrepancy. The study, which was recently published in the journal Nature Communications, could significantly advance research into our planet's climate history.

During transitions from glacials to interglacials, the glaciers on Greenland and in North America and Europe wax and wane ...

2021-02-23

A simple but powerful idea is to improve the health of corals using cocktails of beneficial bacteria. The strategy is being explored as part of global scientific efforts to help corals become stronger, more stress resistant and more likely to survive bleaching events associated with climate change.

Corals rely on bacterial and algal symbionts to provide nutrients, energy (through photosynthesis), toxin regulation and protection against pathogenic attacks. This complex and finely balanced relationship underpins the health of the holobiont and coral reefs as a whole.

Rather like the use of probiotics in plant science to improve ...

2021-02-23

Members of the German Bundestag who belong to underrepresented groups are more active in the legislative process and, early on, typically tend to advocate more for the interests of their groups. However, a current study by the universities in Konstanz, Basel, Geneva and Stuttgart indicates that, after a few years, most of them do move on to other political fields. This is tied to the career-related incentives these elected representatives face: At first, their careers in parliament benefit from their ability to speak for underrepresented groups. As their careers progress, however, they are required to demonstrate expertise in areas beyond the interests of these groups, the researchers conclude.

The study was led by Professor Christian Breunig, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Fat cells may influence how the body reacts to heart failure, study shows

Promising results in mice open door to new areas of research in treating patients with heart failure.