(Press-News.org) In Wonderland, Alice drank a potion to shrink herself. In nature, some animal species shrink to escape the attention of human hunters, a process that takes from decades to millennia. To begin to understand the genetics of shrinking, scientists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama successfully extracted DNA from marine shells. Their new technique will not only shed light on how animals from lizards to lemurs shrink, it will reveal many other stories hidden in shells.

"Humans are unique as predators," said Alexis Sullivan, doctoral student at Penn State University who did the field research as a short-term fellow at STRI. "Most other animals go for smaller, younger, older or injured prey that are easy to catch, but humans often take the largest individual to feed many mouths or to display as a trophy."

This preference for the biggest means the smaller individuals tend to survive and reproduce, which over time leads to the evolution of smaller individuals in the population. Sullivan's father was a hunter, and she remembers being intrigued as a child when he would choose to spare the lives of the largest bucks to keep this from happening in the local deer population.

When she joined George Perry's lab at Penn State, they wrote a paper that reviewed 'the deep history of human entanglement' with animals and plants, and how these organisms have physically changed because of human behaviors. Sullivan hoped to write her dissertation about lemurs, which have become almost 10% smaller in only 1,000 years, presumably as a result of human hunting. But because lemurs are primates, endangered, and live in Madagascar, the logistics, not to mention the cost, of sampling modern and ancient lemur DNA were daunting.

At the same time, Sullivan and Perry were fascinated by a study by a staff scientist at STRI, Aaron O'Dea, and colleagues, who showed that marine snails called fighting conch, commonly eaten as ceviche or fritters by Caribbean coastal residents, have steadily become smaller in areas where they were harvested for food. Modern shells contained 66% less meat than shells from ancient "pristine" reefs. The logistics of working at the Smithsonian's Bocas del Toro Research Station were straightforward, but no one had ever extracted DNA from tropical shells before--modern or ancient.

"Most of the ancient DNA that had been sequenced was from animals or plants in permafrost which helps preserve the DNA," Sullivan said. "We had no idea whether DNA would survive in a tropical environment for thousands of years."

The first step she took was to create a reference sequence from fresh conch tissue. She then moved to the shell itself. Since conch shells have much more calcium carbonate than bone, Sullivan had to modify a standard approach typically used to extract DNA from human skeletal material. This crucial step was recommended by Stephanie Marciniak, a specialist in ancient DNA and post-doctoral fellow in Perry's lab.

After refining the approach, Sullivan then moved to thousand-year-old shells from a trash midden at the Sitio Drago archeological site in Bocas del Toro. This site had been studied by STRI Research Associate and UCLA Professor Tom Wake.

"Those shells had probably been cooked by their pre-Columbian harvesters making Alexis' successful extraction and sequencing of DNA even more incredible," Wake said.

Finally, Sullivan turned to the same species of conch preserved in a mid-Holocene coral reef, again in Bocas del Toro. As they expected, the DNA was poorly preserved, but Sullivan demonstrated that even shells more than 7,000 years old faithfully preserved DNA.

"I was amazed," O'Dea said. "After 7,000 years in temperatures over 20 degrees Celsius, these conch shells still preserved minute fragments of the original animals' DNA. This work opens the door to exploring the genetic changes in the conch associated with size changes over millennia, and it's all down to Alexis' skill and perseverance."

As the team learns more about the biology and genetics of the conch, they will be in a much better position to understand if human harvesting or something else explains why fighting conchs are smaller in areas where they are frequently harvested.

"We are especially grateful to the Cayo Agua community in Bocas del Toro who offered conch shells for our tests," Sullivan said. She hopes to return to Panama soon to share her results with them.

INFORMATION:

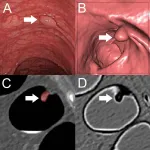

OAK BROOK, Ill. - A machine learning algorithm helps accurately differentiate benign and premalignant colorectal polyps on CT colonography scans, according to a study published in the journal Radiology.

Colorectal cancer is among the three most common causes of cancer-related death among men and women in industrialized countries. Most types of colorectal cancer originate from adenomatous polyps--gland-like growths on the mucous membrane lining the large intestine--that develop over several years. Early detection and removal of these precancerous polyps can reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer.

During the last two decades, CT colonography emerged as a noninvasive ...

Peer review/observational study/people

In patients with severe COVID-19, the innate immune system overreacts. This overreaction may underlie the formation of blood clots (thrombi) and deterioration in oxygen saturation that affect the patients. This is shown in an Uppsala University study published in the journal Frontiers in Immunology.

Blood contains numerous proteins that constitute the body's primary barrier, by both recognising and destroying microorganisms, including SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). These proteins are part of the intravascular innate immune system (IIIS), which consists of certain white blood cells, platelets and what are known as the cascade systems of the blood.

Only 5 ...

Glaciers in West Antarctica are moving more quickly from land into the ocean, contributing to rising global sea levels. A 25-year record of satellite observations has been used to show widespread increases in ice speed across the Getz sector for the first time, with some ice accelerating into the ocean by nearly 50%.

The new study, led by the University of Leeds, reports that 14 glaciers in the Getz region are thinning and flowing more quickly into the ocean. Between 1994 and 2018, 315 gigatonnes of ice has been lost, adding 0.9 mm to global mean sea level - equivalent to 126 million Olympic swimming pools of water.

The results published today (19/02/2021) in the journal Nature Communications show that, on average, ...

A radiotherapy technique which 'paints' tumours by targeting them precisely, and avoiding healthy tissue, has been devised in research led by the University of Strathclyde.

Researchers used a magnetic lens to focus a Very High Electron Energy (VHEE) beam to a zone of a few millimetres. Concentrating the radiation into a small volume of high dose will enable it to be rapidly scanned across a tumour, while controlling its intensity.

It is being proposed as an alternative to other forms of radiotherapy, which can risk non-tumorous tissue becoming overexposed to radiation.

The researchers are planning further investigation, with the use of a purpose-built device.

The study ...

During glacial periods, the sea level falls, because vast quantities of water are stored in the massive inland glaciers. To date, however, computer models have been unable to reconcile sea-level height with the thickness of the glaciers. Using innovative new calculations, a team of climate researchers led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now managed to explain this discrepancy. The study, which was recently published in the journal Nature Communications, could significantly advance research into our planet's climate history.

During transitions from glacials to interglacials, the glaciers on Greenland and in North America and Europe wax and wane ...

A simple but powerful idea is to improve the health of corals using cocktails of beneficial bacteria. The strategy is being explored as part of global scientific efforts to help corals become stronger, more stress resistant and more likely to survive bleaching events associated with climate change.

Corals rely on bacterial and algal symbionts to provide nutrients, energy (through photosynthesis), toxin regulation and protection against pathogenic attacks. This complex and finely balanced relationship underpins the health of the holobiont and coral reefs as a whole.

Rather like the use of probiotics in plant science to improve ...

Members of the German Bundestag who belong to underrepresented groups are more active in the legislative process and, early on, typically tend to advocate more for the interests of their groups. However, a current study by the universities in Konstanz, Basel, Geneva and Stuttgart indicates that, after a few years, most of them do move on to other political fields. This is tied to the career-related incentives these elected representatives face: At first, their careers in parliament benefit from their ability to speak for underrepresented groups. As their careers progress, however, they are required to demonstrate expertise in areas beyond the interests of these groups, the researchers conclude.

The study was led by Professor Christian Breunig, ...

Low-income families have a high awareness of healthy diets but can't afford good quality and nutritious food, new research shows.

The University of York study, in partnership with N8Agrifood, showed that participants tried to eat as much fruit and vegetables as they could within financial constraints, avoiding processed food wherever possible. But there was widespread acknowledgement that processed food was often more accessible than healthy options because of its lower cost.

The researchers said that while the diets of low-income households have been subject ...

Whether it's a "Zoombomb" filled with racial slurs, a racist meme that pops up in a Facebook timeline, or a hate-filled comment on an Instagram post, social media has the power to bring out the worst of the worst.

For college students of color who encounter online racism, the effect of racialized aggressions and assaults reaches far beyond any single social media feed and can lead to real and significant mental health impacts - even more significant than in-person experiences of racial discrimination, according to a recently published study from researchers at UConn and Boston College.

"I think we all suspected that we would find a relationship between the racism online in social media and student mental health," says lead author Adam McCready, an assistant professor-in-residence ...

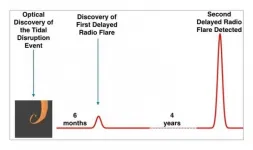

A team of researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI) led by Dr. Assaf Horesh have discovered the first evidence of radio flares emitted only long after a star is destroyed by a black hole. Published in the periodical Nature Astronomy, the discovery relied upon ultra-powerful radio telescopes to study these catastrophic cosmic events in distant galaxies called Tidal Disruption Events (TDE). While researchers had known that these events cause the release of radio flares, this latest discovery saw those flares being emitted months or even years after the stellar disruption. The team was led by Dr. Horesh from the Racah Institute of Physics at the Hebrew together with the NASA Swift space telescope director Professor Brad Cenko and Dr. Iair ...