(Press-News.org) During glacial periods, the sea level falls, because vast quantities of water are stored in the massive inland glaciers. To date, however, computer models have been unable to reconcile sea-level height with the thickness of the glaciers. Using innovative new calculations, a team of climate researchers led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now managed to explain this discrepancy. The study, which was recently published in the journal Nature Communications, could significantly advance research into our planet's climate history.

During transitions from glacials to interglacials, the glaciers on Greenland and in North America and Europe wax and wane over tens of thousands of years. The more water that is stored in the mighty glaciers, the less there is in the oceans - and the lower the sea level is. Climate researchers are now investigating to what extent the glaciers could melt in the coming centuries due to anthropogenic climate change, and how much the sea level would rise as a result. To do so, they're look back into the past. If they can understand the ice growth and melting during past glacials and interglacials, they'll be able to draw valuable conclusions about the future.

The 'missing ice problem'

However, reconstructing the distant past is no mean feat, because the glaciers' thickness and sea level can't be measured directly. Accordingly, climate researchers have to painstakingly gather evidence that they can then use to form a picture of the past. The problem: different pictures emerge, depending on the types of evidence collected. We can't say with absolute certainty what the situation was actually like ten thousand years ago. This 'missing ice problem' remained unsolved for many years. It describes the incongruity of two different scientific approaches that sought to reconcile sea-level height and glacier thickness at the peak of the last glacial, ca. 20,000 years ago. A team of climate experts led by Evan Gowan from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven has now solved the problem using a new method. "It looks like we've found a new way to reconstruct the past as far back as 80,000 years," says Dr Gowan, who has been investigating the problem for roughly a decade. These findings have now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Sediment analysis versus global climate modelling

The 'missing ice problem' is based, on the one hand, on an analysis of sediments from core samples collected from the seafloor in the tropics. These contain traces of corals that can still tell us today to what extent the sea level rose or fell over the millennia. Why? Because corals only live in well-lit waters near the ocean's surface. The sediment cores indicate that 20,000 years ago, the sea level in the tropics implied that sea level was roughly 130 metres lower than it is today. On the other hand, previous models have suggested that the glacial masses weren't large enough 20,000 years ago to explain such a low sea level. To be more precise, for the sea level to be that low, on a global scale an additional volume of water with twice the mass of the Greenland Ice Sheet would have to have been frozen; hence the 'missing ice problem'.

Understanding glacial behaviour

With his new method, Gowan has now reconciled sea level and glacier mass: according to his calculations, the sea level at the time was ca. 116 metres lower than it is today. Based on his approach, there is no discrepancy in terms of glacier mass. Unlike the previous global model, Gowan closely examined the geological conditions in the glaciated regions: how steep was the ice surface? Where did glaciers flow? How much did the rocks and sediment at the base of the ice resist ice flow? His model considers all of these aspects. It also takes into account to what extent the ice sheet pressed down on the Earth's crust in the respective areas. "That depends on how viscous the underlying mantle was," Gowan explains. "We base our calculations on different mantle viscosities, and therefore arrive at different ice masses." The resulting ice masses can now be reconciled with the sea level without any discrepancy.

The established model is flawed

The recent article by Gowan and his team critically re-examines the long-established scientific method used to estimate glacier masses: the oxygen isotope method. Isotopes are atoms of the same element that have different numbers of neutrons and therefore different masses. Oxygen, for example, has a lighter 16O isotope, and a heavier 18O isotope. According to conventional theory, the lighter 16O evaporates from the oceans, while the heavier 18O remains in the water. Accordingly, during glacials, when large inland glaciers form and the volume of water in the oceans decreases, the 18O concentration in the oceans should increase. However, as has been shown, this established model produces discrepancies when it comes to reconciling sea-level height and glacier masses for the period 20,000 years ago and earlier. "For many years, the isotope model has been frequently used to determine the ice volume of glaciers up to several million years ago. Our study calls into question the reliability of this method," says Gowan. His aim is to now use his new method to improve the traditional oxygen isotope method.

INFORMATION:

Original article:

Evan J. Gowan Xu Zhang, Sara Khosravi, Alessio Rovere, Paolo Stocchi, Anna L. C Hughes, Richard Gyllencreutz, Jan Mangerud, John-Inge Svendsen, Gerrit Lohmann: A new global ice sheet reconstruction for the past 80,000 years. Nature Communications (2021);

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-21469-w

A simple but powerful idea is to improve the health of corals using cocktails of beneficial bacteria. The strategy is being explored as part of global scientific efforts to help corals become stronger, more stress resistant and more likely to survive bleaching events associated with climate change.

Corals rely on bacterial and algal symbionts to provide nutrients, energy (through photosynthesis), toxin regulation and protection against pathogenic attacks. This complex and finely balanced relationship underpins the health of the holobiont and coral reefs as a whole.

Rather like the use of probiotics in plant science to improve ...

Members of the German Bundestag who belong to underrepresented groups are more active in the legislative process and, early on, typically tend to advocate more for the interests of their groups. However, a current study by the universities in Konstanz, Basel, Geneva and Stuttgart indicates that, after a few years, most of them do move on to other political fields. This is tied to the career-related incentives these elected representatives face: At first, their careers in parliament benefit from their ability to speak for underrepresented groups. As their careers progress, however, they are required to demonstrate expertise in areas beyond the interests of these groups, the researchers conclude.

The study was led by Professor Christian Breunig, ...

Low-income families have a high awareness of healthy diets but can't afford good quality and nutritious food, new research shows.

The University of York study, in partnership with N8Agrifood, showed that participants tried to eat as much fruit and vegetables as they could within financial constraints, avoiding processed food wherever possible. But there was widespread acknowledgement that processed food was often more accessible than healthy options because of its lower cost.

The researchers said that while the diets of low-income households have been subject ...

Whether it's a "Zoombomb" filled with racial slurs, a racist meme that pops up in a Facebook timeline, or a hate-filled comment on an Instagram post, social media has the power to bring out the worst of the worst.

For college students of color who encounter online racism, the effect of racialized aggressions and assaults reaches far beyond any single social media feed and can lead to real and significant mental health impacts - even more significant than in-person experiences of racial discrimination, according to a recently published study from researchers at UConn and Boston College.

"I think we all suspected that we would find a relationship between the racism online in social media and student mental health," says lead author Adam McCready, an assistant professor-in-residence ...

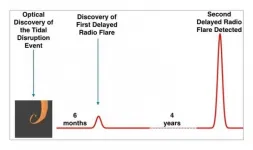

A team of researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI) led by Dr. Assaf Horesh have discovered the first evidence of radio flares emitted only long after a star is destroyed by a black hole. Published in the periodical Nature Astronomy, the discovery relied upon ultra-powerful radio telescopes to study these catastrophic cosmic events in distant galaxies called Tidal Disruption Events (TDE). While researchers had known that these events cause the release of radio flares, this latest discovery saw those flares being emitted months or even years after the stellar disruption. The team was led by Dr. Horesh from the Racah Institute of Physics at the Hebrew together with the NASA Swift space telescope director Professor Brad Cenko and Dr. Iair ...

Selenium contamination of freshwater ecosystems is an ongoing environmental health problem around the world. A naturally occurring trace element, selenium levels are high in some geologic formations like sedimentary shales that form much of the bedrock in the Western United States. Soils derived from this bedrock, and weathering of shale outcrops, can contribute high levels of selenium to surrounding watersheds.

New research out today in Environmental Science & Technology from UConn Assistant Professor of Natural Resources and the Environment Jessica Brandt with Travis Schmidt and colleagues at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) investigates some of the complexities of selenium and how it moves through the ecosystem during runoff ...

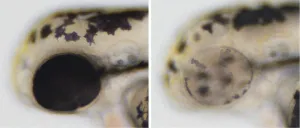

To discover the function of a gene researchers turn it off and observe the consequences. Often genes have multiple functions that differ depending on a tissue and age. Some genes are essential to growth and turning them off too early can have profound consequences that can make observing other functions impossible. To avoid it, researchers have been using conditional gene inactivation which allows turning a gene off only in a specific tissue or later in development, e.g., in adulthood.

One of the systems used for conditional gene inactivation is Cre/lox. "It is the gold standard for the conditional gene inactivation in mice but over time has also become quite important in other model ...

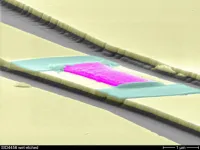

New storage and information technology requires new higher performance materials. One of these materials is yttrium iron garnet, which has special magnetic properties. Thanks to a new process, it can now be transferred to any material. Developed by physicists at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU), the method could advance the production of smaller, faster and more energy-efficient components for data storage and information processing. The physicists have published their results in the journal "Applied Physics Letters".

Magnetic materials play a major role in the development of ...

The way a fish swims reveals a lot about its personality, say scientists

Personality has been described in all sorts of animal species, from ants to apes. Some individuals are shy and sedentary, while others are bold and active. Now a new study published in Ecology and Evolution has revealed that the way a fish swims tells us a lot about its personality.

This new research suggests experts can reliably measure animal personality simply from the way individual animals move, a type of micropersonality trait, and that the method could be used to help scientists understand about personality differences in wild animals.

A team of biologists and mathematicians from Swansea University and the University of Essex filmed the movements of 15 three-spined stickleback ...

A new analysis of B cells and more than 1,000 different monoclonal antibodies from 8 patients with COVID-19 shows that, contrary to previous hypotheses, protective B cell responses to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein remain stable and continue to evolve over a 5-month period, many months after the initial period of active viral replication. However, a large proportion of the neutralizing antibodies generated from these long-lasting B cells did not efficiently recognize various emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants from Brazil and South Africa. These results - from an academia-industry collaboration - will help inform the design of future COVID-19 vaccines that work to constrain viral evolution and stimulate ...