(Press-News.org) Responding to artificial intelligence's exploding demands on computer networks, Princeton University researchers in recent years have radically increased the speed and slashed the energy use of specialized AI systems. Now, the researchers have moved their innovation closer to widespread use by creating co-designed hardware and software that will allow designers to blend these new types of systems into their applications.

"Software is a critical part of enabling new hardware," said Naveen Verma, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Princeton and a leader of the research team. "The hope is that designers can keep using the same software system - and just have it work ten times faster or more efficiently."

By cutting both power demand and the need to exchange data from remote servers, systems made with the Princeton technology will be able to bring artificial intelligence applications, such as piloting software for drones or advanced language translators, to the very edge of computing infrastructure.

"To make AI accessible to the real-time and often personal process all around us, we need to address latency and privacy by moving the computation itself to the edge," said Verma, who is the director of the University's Keller Center for Innovation in Engineering Education. "And that requires both energy efficiency and performance."

Two years ago, the Princeton research team fabricated a new chip designed to improve the performance of neural networks, which are the essence behind today's artificial intelligence. The chip, which performed tens to hundreds of times better than other advanced microchips, marked a revolutionary approach in several measures. In fact, the chip was so different than anything being used for neural nets that it posed a challenge for the developers.

"The chip's major drawback is that it uses a very unusual and disruptive architecture," Verma said in a 2018 interview. "That needs to be reconciled with the massive amount of infrastructure and design methodology that we have and use today."

Over the next two years, the researchers worked to refine the chip and to create a software system that would allow artificial intelligence systems to take advantage of the new chip's speed and efficiency. In a presentation to the International Solid-State Circuits Virtual Conference on Feb. 22, lead author Hongyang Jia, a graduate student in Verma's research lab, described how the new software would allow the new chips to work with different types of networks and allow the systems to be scalable both in hardware and execution of software.

"It is programmable across all these networks," Verma said. "The networks can be very big, and they can be very small."

Verma's team developed the new chip in response to growing demand for artificial intelligence and to the burden AI places on computer networks. Artificial intelligence, which allows machines to mimic cognitive functions such as learning and judgement, plays a critical role in new technologies such as image recognition, translation, and self-driving vehicles. Ideally, the computation for technology such as drone navigation would be based on the drone itself, rather than in a remote network computer. But digital microchips' power demand and need for memory storage can make designing such a system difficult. Typically, the solution places much of the computation and memory on a remote server, which communicates wirelessly with the drone. But this adds to the demands on the communications system, and it introduces security problems and delays in sending instructions to the drone.

To approach the problem, the Princeton researchers rethought computing in several ways. First, they designed a chip that conducts computation and stores data in the same place. This technique, called in-memory computing, slashes the energy and time used to exchange information with dedicated memory. The technique boosts efficiency, but it introduces new problems: because it crams the two functions into a small area, in-memory computing relies on analog operation, which is sensitive to corruption by sources such as voltage fluctuation and temperature spikes. To solve this problem, the Princeton team designed their chips using capacitors rather than transistors. The capacitors, devices that store an electrical charge, can be manufactured with greater precision and are not highly affected by shifts in voltage. Capacitors can also be very small and placed on top of memory cells, increasing processing density and cutting energy needs.

But even after making analog operation robust, many challenges remained. The analog core needed to be efficiently integrated in a mostly digital architecture, so that it could be combined with the other functions and software needed to actually make practical systems work. A digital system uses off-and-on switches to represent ones and zeros that computer engineers use to write the algorithms that make up computer programming. An analog computer takes a completely different approach. In an article in the IEEE Spectrum, Columbia University Professor Yannis Tsividis described an analog computer as a physical system designed to be governed by equations identical to those the programmer wants to solve. An abacus, for example, is a very simple analog computer. Tsividis says that a bucket and a hose can serve as an analog computer for certain calculus problems: to solve an integration function, you could do the math, or you could just measure the water in the bucket.

Analog computing was the dominant technology through the Second World War. It was used to perform functions from predicting tides to directing naval guns. But analog systems were cumbersome to build and usually required highly trained operators. After the emergency of the transistor, digital systems proved more efficient and adaptable. But new technologies and new circuit designs have allowed engineers to eliminate many shortcomings of the analog systems. For applications such as neural networks, the analog systems offer real advantages. Now, the question is how to combine the best of both worlds.

Verma points out that the two types of systems are complimentary. Digital systems play a central role while neural networks using analog chips can run specialized operations extremely fast and efficiently. That is why developing a software system that can integrate the two technologies seamlessly and efficiently is such a critical step.

"The idea is not to put the entire network into in-memory computing," he said. "You need to integrate the capability to do all the other stuff and to do it in a programmable way."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Verma and Jia, the authors include Hossein Valavi, a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton; Jinseok Lee, Murat Ozatay, Rakshit Pathak and Yinqi Tang, graduate students at Princeton. Support for the project was supported in part by the Princeton University School of Engineering and Applied Science through the generosity of William Addy '82.

More U.S. adults reported receiving or planning to receive an influenza vaccination during the 2020-2021 flu season than ever before, according to findings from a national survey.

The survey of 1,027 adults, conducted by the University of Georgia, found that 43.5% of respondents reported having already received a flu vaccination with an additional 13.5% stating they "definitely will get one" and 9.3% stating they "probably will get one." Combined, 66.3% have received or intend to receive an influenza vaccination.

By comparison, 48.4% of adults 18 and older received the vaccine during the 2019-2020 flu season, according to the Centers for Disease ...

A new analysis of education debates on both social media and in traditional media outlets suggests that the education sector is being increasingly influenced by populism and the wider social media 'culture wars'.

The study also suggests that the type of populism in question is not quite the same as that used to explain large-scale political events, such as the UK's 'Brexit' from the European Union, or Donald Trump's recent presidency in the United States.

Instead, the researchers - from the University of Cambridge, UK, and Queensland University of Technology, Australia - identify a phenomenon called 'micropopulism': a localised populism which spotlights an aspect of public ...

CHICAGO, February 24, 2021 -- Despite having been designated as high risk for COVID-19 by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a new study finds 3.1 percent of dental hygienists have had COVID-19 based on data collected in October 2020. This is in alignment with the cumulative infection prevalence rate among dentists and far below that of other health professionals in the U.S, although slightly higher than that of the general population.

The research, published by The Journal of Dental Hygiene, is the first large-scale collection and publication of U.S. dental hygienists' infection rates and infection control practices related to COVID-19. In partnership, the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) and the American Dental Association (ADA) ...

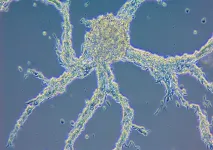

The transition from single-celled organisms to multicellular ones was a major step in the evolution of complex life forms. Multicellular organisms arose hundreds of millions of years ago, but the forces underlying this event remain mysterious. To investigate the origins of multicellularity, Erika Pearce's group at the MPI of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Freiburg turned to the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, which can exist in both a unicellular and a multicellular state, lying on the cusp of this key evolutionary step. These dramatically different states depend on just one thing - food.

A core question of Pearce's lab is to answer how changes in metabolism drive cell function and differentiation. Usually, they study immune cells ...

People who have had evidence of a prior infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, appear to be well protected against being reinfected with the virus, at least for a few months, according to a newly published study from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This finding may explain why reinfection appears to be relatively rare, and it could have important public health implications, including decisions about returning to physical workplaces, school attendance, the prioritization of vaccine distribution, and other activities.

For the study, researchers at NCI, part of the National Institutes of Health, collaborated with ...

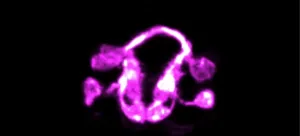

The formation of a brain is one of nature's most staggeringly complex accomplishments. The intricate intermingling of neurons and a labyrinth of connections also make it a particularly difficult feat for scientists to study.

Now, Yale researchers and collaborators have devised a strategy that allows them to see this previously impenetrable process unfold in a living animal -- the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, they report February 24 in the journal Nature.

"Before, we were able to study single cells, or small groups of cells, in the context of the living C. elegans, and for relatively short periods of time," said Mark Moyle, an associate research scientist in neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine and first author of the study. "It has been a breathtaking experience to ...

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Understanding how the brain works is a paramount goal of medical science. But with its billions of tightly packed, intermingled neurons, the human brain is dauntingly difficult to visualize and map, which can provide the route to therapies for long-intractable disorders.

In a major advance published next week in Nature, scientists for the first time report the structure of a fundamental type of tissue organization in brains, called neuropil, as well as the developmental pathways that lead to neuropil assembly in the roundworm C. elegans. This multidisciplinary study ...

What The Study Did: Medicare claims and clinical data were used to estimate health care costs associated with delirium in older adults one year after major elective surgery.

Authors: Tammy T. Hshieh, M.D., M.P.H., of Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.7260)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

What The Study Did: Researchers use a large set of clinical laboratory data linked to other clinical information such as claims to investigate the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 antibody status and subsequent nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) results in an effort to understand how serostatus may predict risk of reinfection.

Authors: Lynne T. Penberthy, M.D., M.P.H., of the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Maryland, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0366)

Editor's ...

In the last 60,000 years, humans have emerged as an ecologically dominant species and have successfully colonized every terrestrial habitat. Our evolutionary success has been facilitated by a heavy reliance on an ever-advancing technology. Understanding how human technology evolves is crucial to understanding why humans have enjoyed such unprecedented evolutionary success.

ASU doctoral graduate Jacob Harris, working with ASU researcher Robert Boyd and Brian Wood from the University of California Las Angeles and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, are interested in the role of causal ...