The Canadian research team was the first to use gene therapy in 2017 to treat patients with Fabry disease, a rare, chronic illness that can damage major organs and shorten lives. They report their findings today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Being one of the first people in the world to receive this treatment, and seeing how much better I felt afterward, it definitely gives me hope that this can help many other Fabry patients and potentially those with other single gene mutation disorders," says Ryan Deveau, one of the participating patients in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. "Now that I don't have to get the replacement therapy every two weeks, I have more time to spend with my family."

Fabry patients currently must undergo enzyme therapy infusions every two weeks. Gene therapy would enable them to receive a single treatment that could prove to be more effective clinically since the modified blood stem cells continuously produce corrected versions of the defective enzyme.

"To date, we can say that the gene therapy has either partially or fully restored enzyme levels to a point where they are no longer considered deficient," says Dr. Aneal Khan, the Alberta Health Services medical geneticist and member of the Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, who is leading the experimental trial in Calgary.

"These results show that just one treatment of gene therapy was enough to benefit patients. Now we need to see whether this single dose can last for the long term."

Five men participated in the study and were treated at Alberta Health Services' Foothills Medical Centre in Calgary, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, and Nova Scotia Health's Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in Halifax.

As a result of the gene therapy, all patients began producing the corrected version of the enzyme to near normal levels within one week. With these initial results, all five patients are approved by Health Canada to stop their intravenous enzyme therapy. So far, three patients have chosen to do so, and are stable.

"This really was a ground-breaking study, given current therapies are not cures," says Dr. Michael West, nephrologist and Nova Scotia Health co-investigator, with Dr. Stephen Couban, a hematologist. "This is the next step in moving toward a better therapy and hopefully a cure for this disease, which can really cause patients a lot of pain and suffering. It's promising that the participating patients are still seeing benefit from the treatment several years after the procedure was completed."

Patients were followed from January 2017 to February 2020 for this study, and ongoing follow-up will extend until February 2024.

Clinicians emphasize it will take many years of further testing before this experimental treatment becomes a clinically available standard of care.

"To actually see that this therapy was working in patients was humbling," says Dr. Jeffrey Medin, who pioneered the treatment while he was a Senior Scientist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network (UHN). Dr. Medin is now the MACC Fund Professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Affiliate Scientist, UHN.

"After 20 years of working on this treatment, to see that patients could end up making their own enzyme, and that the treatment effect was sustained is satisfying. We are elated!"

Darren Bidulka, 52, was the first patient treated in the study on January 11, 2017, at Alberta Health Services' Foothills Medical Centre. He was diagnosed with Fabry disease in 2005, and was on enzyme therapy for years.

"I'm really happy that this worked," he says. "What an amazing result in an utterly fascinating experience. I consider this a great success.

"I can lead a more normal life now without scheduling enzyme therapy every two weeks. This research is also incredibly important for many patients all over the world, who will benefit from these findings."

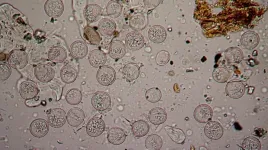

In the study, researchers collected a quantity of a Fabry patient's own blood stem cells, then used a specially engineered virus to inject those cells with copies of the fully functional gene that is responsible for the enzyme. The modified stem cells were then transplanted back into each patient.

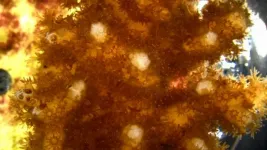

People with Fabry disease have a gene called GLA that does not function correctly. As a result, their bodies are unable to make the correct version of an enzyme that breaks down a fat. A buildup of that can lead to problems in the kidneys, heart and brain.

The treatment, which was approved by Health Canada for experimental purposes, was the first trial in Canada to use a lentivirus in gene therapy. In this case, the specially modified virus was created at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, stripped of its disease-causing capability and augmented with a working copy of the gene that's responsible for the missing enzyme.

Lentiviruses are a family of viruses that can cause diseases like acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and are used world-wide in many clinical trials because of the ease with which they can enter and insert genetic material into cells. They are well understood by the research community, and easy to manufacture in large quantities, which was required for this study.

The trial focused on men because the gene for Fabry disease is on the X-chromosome, so it is inherited as an X-linked disorder. Men are therefore more severely affected than women, because each man carries only one X chromosome.

Men therefore present with more severe symptoms, such as burning in hands and feet, kidney failure, or gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal cramping, frequent bowel movements, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting. Untreated, men have an average lifespan of 58 years and women, 75 years.

An estimated one person in 40,000 to 60,000 has Fabry disease. There are more than 500 people in Canada known to have this illness, although exact numbers are not known due to the difficulty in identifying all those with the disease.

"Studies such as this can pave the way for additional clinical trials in Fabry disease and for many other metabolic disorders. It also shows that it is possible to coordinate such a complex study at multiple sites, even across international borders, as some analyses were done at the Medical College of Wisconsin," says Dr. Medin, who has been working on the project since he was at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD.

INFORMATION:

Competing Interests

UHN has a financial interest in a licensing agreement with AVROBIO, Inc., granting AVROBIO exclusive rights to manufacture and commercialize the gene therapy studied in this Phase 1 clinical trial.

Aneal Khan: AVROBIO: consulting fees, grants, revenue distribution agreement, speaker fees and

travel support; University Health Network: revenue distribution agreement.

Anthony Rupar: AVROBIO: service contract.

Christiane Auray-Blais: AVROBIO: honoraria and service contract.

Armand Keating: AVROBIO: consulting fees unrelated to this study.

Michael L. West: Amicus Therapeutics: consulting fees, grants, speaker fees and travel support;

Protalix: consulting fees, grants, speaker fees and travel support; Sanofi-Genzyme: consulting fees, grants, speaker fees and travel support; Takeda Pharmaceuticals: consulting fees, grants, speaker fees and travel support; and University Health Network: revenue distribution agreement.

Jeffrey A. Medin: AVROBIO: scientific co-founder and shareholder; Rapa Therapeutics: scientific advisory board; Sanofi-Genzyme: honorarium, Shire: honorarium.

Support for this study provided by: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Kidney Foundation of Canada and the MACC Fund, and AVROBIO, Inc. Juravinski Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre and Université de Sherbrooke provided critical laboratory support in stem and progenitor cell isolation, assay of enzymatic activity and metabolite levels, respectively.

About Princess Margaret Cancer Centre

Princess Margaret Cancer Centre has achieved an international reputation as a global leader in the fight against cancer and delivering personalized cancer medicine. The Princess Margaret, one of the top five international cancer research centres, is a member of the University Health Network, which also includes Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute and the Michener Institute for Education at UHN. All are research hospitals affiliated with the University of Toronto. For more information: http://www.theprincessmargaret.ca

About Alberta Health Services

Alberta Health Services is the provincial health authority responsible for planning and delivering health supports and services for more than four million adults and children living in Alberta. Its mission is to provide a patient-focused, quality health system that is accessible and sustainable for all Albertans.

About Nova Scotia Health

Nova Scotia Health provides health services to Nova Scotians and a wide array of specialized services to Maritimers and Atlantic Canadians. Nova Scotia Health operates hospitals, health centres and community-based programs across the province. Our team of health professionals includes employees, doctors, researchers, learners and volunteers. We work in partnership with community groups, schools, governments, foundations and auxiliaries and community health boards.