How SARS-CoV-2's sugar-coated shield helps activate the virus

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is coated with sugars called glycans, which help it evade the immune system; new research shows precisely how those sugars help the virus become activated and infectious and could help with vaccine and drug disc

2021-02-25

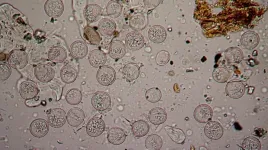

(Press-News.org) ROCKVILLE, MD - One thing that makes SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, elusive to the immune system is that it is covered in sugars called glycans. Once SARS-CoV-2 infects someone's body, it becomes covered in that person's unique glycans, making it difficult for the immune system to recognize the virus as something it needs to fight. Those glycans also play an important role in activating the virus. Terra Sztain-Pedone, a graduate student, and colleagues in the labs of Rommie Amaro at the University of California, San Diego and Lillian Chong at the University of Pittsburgh, studied exactly how the glycans activate SARS-CoV-2. Sztain-Pedone will present the research on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society.

For SARS-CoV-2 to become activated and infectious, the spike proteins on the outside of the virus need to change shape so it can stick to our cells. Scientists knew that the glycans that coat these spikes help SARS-CoV-2 evade the immune system, but it was not known what role they played in the activation process. Studying these molecules is tricky because they are so small and have many parts that move in subtle ways. "There are half a million atoms in just one of these spike protein simulations," Sztain-Pedone explained.

Using advanced High Performance Computing algorithms that run many simulations in parallel, the research team examined how the positions of each of those atoms changes as the SARS-CoV-2 spike becomes activated. "Most computers wouldn't be able to do this with half a million atoms," Sztain-Pedone says.

The team was able to identify the glycans and molecules that are responsible for activating the spike protein. "Surprisingly, one glycan seems to be responsible for initiating the entire opening," Sztain-Pedone says. Other glycans are involved in subsequent steps. To validate their findings, the team is currently working with Jason McLellan, a professor at the University of Texas, Austin, and colleagues who are performing experiments with spike proteins in the lab.

There is potential to use the simulations developed by Sztain-Pedone and colleagues to identify treatments that will block or prevent SARS-CoV-2 activation. "Because we have all these structures, we can do small molecule screening with computational algorithms," Sztain-Pedone explained. They can also study new virus mutations, such as the B.1.1.7 variant that is currently spreading, to "look at how that might affect the spike protein activation," Sztain-Pedone says.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-25

(Thursday, Feb. 25, 2021, Toronto)--Results of a world-first Canadian pilot study on patients treated with gene therapy for Fabry disease show that the treatment is working and safe.

The Canadian research team was the first to use gene therapy in 2017 to treat patients with Fabry disease, a rare, chronic illness that can damage major organs and shorten lives. They report their findings today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Being one of the first people in the world to receive this treatment, and seeing how much better I felt afterward, it definitely gives me hope that this can help many other Fabry patients and potentially those with other single gene mutation disorders," says Ryan Deveau, one of the ...

2021-02-25

Chimpanzees and humans "overlap" in their use of forests and even villages, new research shows.

Scientists used camera traps to track the movements of western chimpanzees - a critically endangered species - in Guinea-Bissau.

Chimpanzees used areas away from villages and agriculture more intensively, but entered land used by humans to get fruit - especially when wild fruits were scarce.

Researchers from the University of Exeter and Oxford Brookes University say the approach used in this study could help to inform a "coexistence strategy" for chimpanzees ...

2021-02-25

Allergy sufferers are no strangers to problems with pollen. But now - due to climate change - the pollen season is lasting longer and starting earlier than ever before, meaning more days of itchy eyes and runny noses. Warmer temperatures cause flowers to bloom earlier, while higher CO2 levels cause more pollen to be produced.

The effects of climate change on the pollen season have been studied at-length, and END ...

2021-02-25

Although guidelines do not recommend use of opioids to manage pain for individuals with knee osteoarthritis, a recent study published early online in END ...

2021-02-25

Liquid structures - liquid droplets that maintain a specific shape - are useful for a variety of applications, from food processing to cosmetics, medicine, and even petroleum extraction, but researchers have yet to tap into these exciting new materials' full potential because not much is known about how they form.

Now, a research team led by Berkeley Lab has captured real-time high-resolution videos of liquid structures taking shape as nanoparticle surfactants (NPSs) - soap-like particles just billionths of a meter in size - jam tightly together, ...

2021-02-25

Pheasants fall into two groups in terms of how they find their way around - and the different types prefer slightly different habitats, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists tested whether individual pheasants used landmarks (allocentric) or their own position (egocentric) to learn the way through a maze.

The captive-bred pheasants were later released into the wild, and their choice of habitat was observed.

All pheasants favoured woodland, but allocentric navigators spent more time out in the open, where their landmark-based style is more useful.

"Humans tend to use both of these navigational tactics and quite frequently combine them, ...

2021-02-25

In a major advance in the treatment of multiple myeloma, a CAR T-cell therapy has generated deep, sustained remissions in patients who had relapsed from several previous therapies, an international clinical trial has found.

In a study posted online today by the New England Journal of Medicine, trial leaders report that almost 75% of the participants responded to the therapy, known as idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel), and one-third of them had a complete response, or disappearance of all signs of their cancer. These rates, and the duration of the responses, are significantly ...

2021-02-25

The genetic tool CRISPR has been likened to molecular scissors for its ability to snip out and replace genetic code within DNA.

But CRISPR has a capability that could make it useful beyond genetic repairs. "CRISPR can precisely locate specific genes," says Lacramioara Bintu, an assistant professor of bioengineering at Stanford. "What we did was attach CRISPR to nanobodies to help it perform specific actions when it reached the right spot on DNA."

Her lab recently used this combo technique to transform CRISPR from a gene-editing scissors into a nanoscale control agent that can toggle specific genes on and off, like a light switch, to start or stop the flow of some health-related protein inside a cell.

"There are a lot of things you can't fix ...

2021-02-25

Baby mice might be small, but they're tough, too.

For their first seven days of life, they have the special ability to regenerate damaged heart tissue.

Humans, on the other hand, aren't so lucky: any heart injuries we suffer could lead to permanent damage. But what if we could learn to repair our hearts, just like baby mice?

A team of researchers led by UNSW Sydney have developed a microchip that can help scientists study the regenerative potential of mice heart cells. This microchip - which combines microengineering with biomedicine - could help pave the way for new regenerative heart medicine research.

The study is featured on the cover ...

2021-02-25

BROOKLYN, New York, Wednesday, February 24, 2021 - Travel bans have been key to efforts by many countries to control the spread of COVID-19. But new research aimed at providing a decision support system to Italian policy makers, recently published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, suggests that reducing individual activity (i.e., social distancing, closure of non-essential business, etc.) is far superior in controlling the dissemination of Sars-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

The research, which has implications for the United States and other countries, found that limiting personal mobility through travel restrictions and similar tactics is effective only in the first phases of the epidemic, and reduces in proportion to the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How SARS-CoV-2's sugar-coated shield helps activate the virus

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is coated with sugars called glycans, which help it evade the immune system; new research shows precisely how those sugars help the virus become activated and infectious and could help with vaccine and drug disc