CUHK unveils balance between two protein counteracting forces in hereditary ataxias

Providing new direction for SCA3 therapeutic intervention

2021-03-01

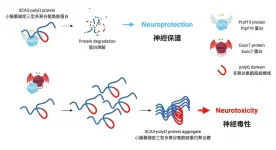

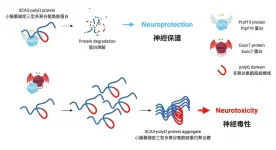

(Press-News.org) Collaborating with the University of Oxford, Professor Ho Yin Edwin Chan's research team from the School of Life Sciences of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) recently unveiled the counteracting relationship between pre-mRNA-processing factor 19 (Prpf19) and exocyst complex component 7 (Exoc7) in controlling the degradation of disease protein and neurodegeneration of the rare hereditary ataxia. The research findings have been published in the prestigious scientific journal, Cell Death & Disease.

Protein misfolding contributes to the pathogenesis of SCA3

Proteins play a significant role in every single cell development in the human body, including neurons. Numerous studies have proved that misfolds and aggregation of proteins contribute to many occurrences of human diseases. Proteins need to adopt proper folding and architecture before being able to execute their biological functions. Even a minor improper assembly of a protein may result in cellular malfunctioning, leading to toxic insoluble protein aggregates that cause diseases. Progressive misfolding of proteins and aggregates will interfere with the functionalities of other normal proteins, and these are also detected in the deteriorating neurons of SCA3 and other protein misfolding induced disorders, including polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases.

Prpf19 is capable of degrading toxic expanded SCA3-polyQ protein

Professor Edwin Chan, Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Zhefan Stephen Chen, and the team discovered that the nuclear-localised protein Prpf19 is responsible for scrutinising the quality of SCA3-polyQ, the disease protein of SCA3 or MJD. Potentiating the function of Prpf19 promotes degradation of faculty SCA3-polyQ protein via a process called ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. In this, the toxicity of SCA3 cells is proved to be alleviated, and improvement is also shown in the condition of neurodegeneration and the nervous system of the animal model with SCA3 disease.

The rivalry between Prpf19 and Exoc7 in controlling neurodegeneration of SCA3

Exoc7 is a protein that controls trafficking of proteins within cells, and it is also known as an associating partner of Prpf19. While the coiled-coil domain of Exoc7, a special region of the protein, is crucial for Exoc7 to restrain Prpf19 from functioning, the research team has further discovered that Exoc7 will shuttle to the cell nucleus where it binds directly to Prpf19 and interferes with the pre-mRNA splicing, causing Prpf19 to lose its beneficial effects on SCA3 or MJD disease models.

Professor Chan said, "The current study demonstrates an intricate relationship between Prpf19 and Exoc7, two crucial proteins in nerve cells. Elucidating the mechanism of action of protein networks that govern protein aggregation will allow us to develop potential small molecules or activators targeting Prpf19, with the hope of providing novel strategies for curing SCA3/MJD and other neurodegenerative disorders. Today (28 February) marks the Rare Disease Day 2021. SCA3/MJD belongs to the category of rare neurodegenerative diseases, I also hope our findings will provide an insight into rare disease translational biomedicine research."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the General Research Fund and Area of Excellence Scheme of the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong, and The CUHK Gerald Choa Neuroscience Centre. The full text of the research paper can be found: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41419-021-03444-x.

Brief biography of Professor Ho Yin Edwin Chan

Professor Ho Yin Edwin Chan is Professor in the School of Life Sciences, CUHK. He received undergraduate training in biochemistry from CUHK, doctoral training at The University of Cambridge (UK), and postdoctoral training at The University of Pennsylvania (US). Since 1999, Professor Chan has been investigating rare neurological and neuromuscular disorders. In 2014, he established an intercontinental research collaboration network on rare neuronal diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia, Huntington's disease, myotonic dystrophy and spinocerebellar ataxias. Professor Chan actively participates in community services, including as chairperson of the scientific and medical advisory committee of Hong Kong Spinocerebellar Ataxia Association, and Founder of Nexus of Rare Neurodegenerative Diseases. He is a Founding Member and Executive Committee member of The Young Academy of Sciences of Hong Kong.

Brief biography of Dr. Zhefan Stephen Chen

Dr. Zhefan Stephen Chen received his Ph.D. degree at the School of Life Sciences, CUHK. He is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow under the Clinical Neurosciences programme between The Chinese University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford (Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Pembroke College). During his stay in Oxford, Dr. Chen was under the supervision of Professor Kevin Talbot, Professor of Motor Neurone Biology and Head of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, UK.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-01

A new paper by Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Prof. Ran Barkai from the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University proposes an original unifying explanation for the physiological, behavioral and cultural evolution of the human species, from its first appearance about two million years ago, to the agricultural revolution (around 10,000 BCE). According to the paper, humans developed as hunters of large animals, causing their ultimate extinction. As they adapted to hunting small, swift prey animals, humans developed higher cognitive abilities, evidenced by the most obvious evolutionary change - the growth of brain volume from ...

2021-03-01

A study carried out by researchers from the Institute of Genomics, University of Tartu revealed that human gut microbiome can be used to predict changes in Type 2 diabetes related glucose regulation up to four years ahead.

Type 2 diabetes is a metabolic disease characterized by elevated blood glucose levels that contributes to millions of deaths worldwide each year and its prevalence is rapidly increasing. Type 2 diabetes is preceded by "prediabetes" - a condition when the glucose levels have started to rise, but the progression of the disease ...

2021-03-01

Takeaway coffees - they're a convenient start for millions of people each day, but while the caffeine perks us up, the disposable cups drag us down, with nearly 300 billion ending up in landfill each year.

While most coffee drinkers are happy to make a switch to sustainable practices, new research from the University of South Australia shows that an absence of infrastructure and a general 'throwaway' culture is severely delaying sustainable change.

It's a timely finding, particularly given the new bans on single-use plastics coming into effect in South Australia today, and the likelihood of takeaway coffee cups taking ...

2021-03-01

Tsukuba, Japan - Single-celled algae and animal sperm cells are widely separated in evolution but both swim in the same way, by waving their protruding hairs, called cilia or flagella. Motion is driven by molecular motors, complex assemblies of proteins that exert a force when changing shape. The motor proteins are connected to the cell's internal skeleton of microtubules; the moving force from the motor causes microtubules to slide, moving the flagella and propelling the cell.

Now a team led by Professor Kazuo Inaba of the University of Tsukuba in collaboration with scientists from Osaka University, Tokyo Institute of Technology and Paul Scherrer Institute has described a new protein that is closely ...

2021-03-01

While many people believe misinformation on Facebook and Twitter from time to time, people with lower education or health literacy levels, a tendency to use alternative medicine or a distrust of the health care system are more likely to believe inaccurate medical postings than others, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

"Inaccurate information is a barrier to good health care because it can discourage people from taking preventive measures to head off illness and make them hesitant to seek care when they get sick," said lead author Laura D. Scherer, PhD, with the University of Colorado School of Medicine. "Identifying who is most susceptible to misinformation ...

2021-03-01

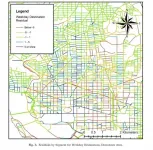

Electric scooters or "e-scooters" are taking over cities worldwide and have broad appeal with tourists. Although e-scooter use declined during the COVID-19 pandemic, its popularity could rebound rapidly, especially if travelers start to substitute scooters for transit on some shorter trips. Shared e-scooters in particular, are a rapidly emerging mode of transportation, but present a host of regulatory challenges from equitable distribution to parking infrastructure to pedestrian safety, among others.

Understanding travel demand patterns of shared ...

2021-03-01

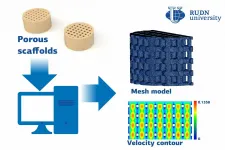

An associate professor from RUDN University found out the effect of the number and size of pores on the permeability of bone implants by biological fluids. The results of the study could help choose the optimal physical parameters of implants. The results of the study were published in the International Journal of Engineering.

For an implant to survive in the body and to take the place of bone tissue, it should be made of a non-toxic, biologically inert, and wearproof material. However, at the same time, it should be light, porous, and permeable by biological liquids. If an implant does not interfere with the transfer of oxygen, minerals, and nutrients, new bone tissue and blood vessels start to grow around it, and a patient's ...

2021-03-01

Osaka, Japan - Osaka University researchers employed machine learning to design new polymers for use in photovoltaic devices. After virtually screening over 200,000 candidate materials, they synthesized one of the most promising and found its properties were consistent with their predictions. This work may lead to a revolution in the way functional materials are discovered.

Machine learning is a powerful tool that allows computers to make predictions about even complex situations, as long as the algorithms are supplied with sufficient example data. This is especially useful for complicated ...

2021-03-01

With their exuberant colours, fiery personalities and captivating courtship displays, the fairy wrasses are one of the most beloved coral reef fish. Despite this, the evolutionary history of its genus was not well understood - until now.

Fairy wrasses diverged in form and colour after repeated sea level rises and falls during the last ice age, finds a new study. Published in top journal Systematic Biology, it employed a novel genome-wide dataset to make this discovery.

Lead author, ichthyologist and PhD candidate at the University of Sydney, Mr Yi-Kai (Kai) Tea, says ...

2021-03-01

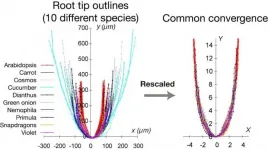

Osaka, Japan - Nature is full of diversity, but underneath the differences are often shared features. Researchers from Japan investigating diversity in plant features have discovered that plant root tips commonly converged to a particular shape because of physical restrictions on their growth.

In a study published in February in Development, researchers from Osaka University, Nara Institute of Science and Technology, and Kobe University have revealed that plant root tips are constrained to a dome-shaped outline because of restrictions on their tissue growth. This study is one of the papers selected as a Research Highlight published in this issue of Development ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] CUHK unveils balance between two protein counteracting forces in hereditary ataxias

Providing new direction for SCA3 therapeutic intervention