(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- Grafting neurons grown from monkeys' own cells into their brains relieved the debilitating movement and depression symptoms associated with Parkinson's disease, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison reported today.

In a study published in the journal Nature Medicine, the UW team describes its success with neurons made from induced pluripotent stem cells from the monkeys' own bodies. This approach avoided complications with the primates' immune systems and takes an important step toward a treatment for millions of human Parkinson's patients.

"This result in primates is extremely powerful, particularly for translating our discoveries to the clinic," says UW-Madison neuroscientist Su-Chun Zhang, whose Waisman Center lab grew the brain cells.

Parkinson's disease damages neurons in the brain that produce dopamine, a brain chemical that transmits signals between nerve cells. The disrupted signals make it progressively harder to coordinate muscles for even simple movements and cause rigidity, slowness and tremors that are the disease's hallmark symptoms. Patients -- especially those in earlier stages of Parkinson's -- are typically treated with drugs like L-DOPA to increase dopamine production.

"Those drugs work well for many patients, but the effect doesn't last," says Marina Emborg, a Parkinson's researcher at UW-Madison's Wisconsin National Primate Research Center. "Eventually, as the disease progresses and their motor symptoms get worse, they are back to not having enough dopamine, and side effects of the drugs appear."

Scientists have tried with some success to treat later-stage Parkinson's in patients by implanting cells from fetal tissue, but research and outcomes were limited by the availability of useful cells and interference from patients' immune systems. Zhang's lab has spent years learning how to dial donor cells from a patient back into a stem cell state, in which they have the power to grow into nearly any kind of cell in the body, and then redirect that development to create neurons.

"The idea is very simple," Zhang says. "When you have stem cells, you can generate the right type of target cells in a consistent manner. And when they come from the individual you want to graft them into, the body recognizes and welcomes them as their own."

The application was less simple. More than a decade in the works, the new study began in earnest with a dozen rhesus monkeys several years ago. A neurotoxin was administered -- a common practice for inducing Parkinson's-like damage for research -- and Emborg's lab evaluated the monkeys monthly to assess the progression of symptoms.

"We evaluated through observation and clinical tests how the animals walk, how they grab pieces of food, how they interact with people -- and also with PET imaging we measured dopamine production," Emborg says. (PET is positron emission tomography, a type of medical imaging.) "We wanted symptoms that resemble a mature stage of the disease."

Guided by real-time MRI that can be used during procedures and was developed at UW-Madison by biomedical engineer Walter Block during the course of the Parkinson's study, the researchers injected millions of dopamine-producing neurons and supporting cells into each monkey's brain in an area called the striatum, which is depleted of dopamine as a consequence of the ravaging effects of Parkinson's in neurons.

Half the monkeys received a graft made from their own induced pluripotent stem cells (called an autologous transplant). Half received cells from other monkeys (an allogenic transplant). And that made all the difference.

Within six months, the monkeys that got grafts of their own cells were making significant improvements. Within a year, their dopamine levels had doubled and tripled.

"The autologous animals started to move more," Emborg says. "Where before they needed to grab the cage to stand up, they started moving much more fluidly and grabbing food much faster and easier."

The monkeys who received allogenic cells showed no such lasting boost in dopamine or improvement in muscle strength or control, and the physical differences in the brains were stark. The axons -- the extensions of nerve cells that reach out to carry electrical impulses to other cells -- of the autologous grafts were long and intermingled with the surrounding tissue.

"They could grow freely and extend far out within the striatum," says Yunlong Tao, a scientist in Zhang's lab and first author of the study. "In the allogenic monkeys, where the grafts are treated as foreign cells by the immune system, they are attacked to stop the spread of the axons."

The missing connections leave the allogenic graft walled off from the rest of the brain, denying them opportunities to renew contacts with systems beyond muscle management.

"Although Parkinson's is typically classified as a movement disorder, anxiety and depression are typical, too," Emborg says. "In the autologous animals, we saw extension of axons from the graft into areas that have to do with what's called the emotional brain."

Symptoms that resemble depression and anxiety -- pacing, disinterest in others and even in favorite treats -- abated after the autologous grafts grew in. The allogenic monkeys' symptoms remained unchanged or worsened.

The results are promising enough that Zhang hopes to begin work on applications for human patients soon. In particular, Zhang says, the work Tao did in the new study to help measure the relationship between symptom improvement, graft size and resulting dopamine production gives the researchers a predictive tool for developing effective human grafts.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS076352, NS096282, NS086604, U54 HD090256 and P51OD011106), the National Medical Research Council of Singapore, the Dr. Ralph & Marian Falk Medical Research Trust and UW-Madison.

Chris Barncard,

barncard@wisc.edu

Additional Contacts: Marina Emborg,

emborg@primate.wisc.edu; Yunlong Tao,

ytao28@wisc.edu

Extreme rainfall associated with climate change is causing harm to babies in some of the most forgotten places on the planet setting in motion a chain of disadvantage down the generations, according to new research in Nature Sustainability.

Researchers from Lancaster University and the FIOCRUZ health research institute in Brazil found babies born to mothers exposed to extreme rainfall shocks, were smaller due to restricted foetal growth and premature birth.

Low birth-weight has life-long consequences for health and development and researchers say their findings are evidence of climate extremes causing intergenerational disadvantage, especially for socially-marginalized Amazonians in forgotten places.

Climate extremes can affect the health of mothers and their unborn babies in ...

BINGHAMTON, NY -- Neandertals -- the closest ancestor to modern humans -- possessed the ability to perceive and produce human speech, according to a new study published by an international multidisciplinary team of researchers including Binghamton University anthropology professor Rolf Quam and graduate student Alex Velez.

"This is one of the most important studies I have been involved in during my career", says Quam. "The results are solid and clearly show the Neandertals had the capacity to perceive and produce human speech. This is one of the very few current, ongoing research lines relying on fossil evidence to study the evolution of language, a notoriously ...

More than 20 million people 65 years and older present to emergency departments each year in the United States. Roughly one third of those patients are admitted to the hospital often because they cannot be safely discharged to their home. For an older patient, hospitalization comes with the increased risk of infection, falls, delirium, functional decline and death. Hospitalizations also come with increased cost to the patient, provider and payer. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the average cost of an inpatient hospital stay is more than $13,800 per Medicare beneficiary.

As the U.S. population ages, more hospitals are implementing geriatric emergency ...

As the planet warms, scientists expect that mountain snowpack should melt progressively earlier in the year. However, observations in the U.S. show that as temperatures have risen, snowpack melt is relatively unaffected in some regions while others can experience snowpack melt a month earlier in the year.

This discrepancy in the timing of snowpack disappearance--the date in the spring when all the winter snow has melted--is the focus of new research by scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

In a new study published March 1 in the journal Nature Climate ...

For the first time, scientists have assessed how many corals there are in the Pacific Ocean--and evaluated their risk of extinction.

While the answer to "how many coral species are there?" is 'Googleable', until now scientists didn't know how many individual coral colonies there are in the world.

"In the Pacific, we estimate there are roughly half a trillion corals," said the study lead author, Dr Andy Dietzel from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU).

"This is about the same number of trees in the Amazon, or ...

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

Toronto, ON - Children in the United States who have more screen time at ages 9-10 are more likely to develop binge-eating disorder one year later, according to a new national study.

The study, published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders on March 1, found that each additional hour spent on social media was associated with a 62% higher risk of binge-eating disorder one year later. It also found that each additional hour spent watching or streaming television or movies led to a 39% ...

HANOVER, N.H. - March 1, 2020 - During World War II, British intelligence agents planted false documents on a corpse to fool Nazi Germany into preparing for an assault on Greece. "Operation Mincemeat" was a success, and covered the actual Allied invasion of Sicily.

The "canary trap" technique in espionage spreads multiple versions of false documents to conceal a secret. Canary traps can be used to sniff out information leaks, or as in WWII, to create distractions that hide valuable information.

WE-FORGE, a new data protection system designed at Dartmouth's Department ...

Assessing a drug compound by its activity, not simply its structure, is a new approach that could speed the search for COVID-19 therapies and reveal more potential therapies for other diseases.

This action-based focus -- called biological activity-based modeling (BABM) -- forms the core of a new approach developed by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) researchers and others. NCATS is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Researchers used BABM to look for potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents whose actions, not their structures, are similar to those of compounds already shown to be effective.

NCATS scientists ...

The hidden social, environmental and health costs of the world's energy and transport sectors is equal to more than a quarter of the globe's entire economic output, new research from the University of Sussex Business School and Hanyang University reveals.

According to analysis carried out by Professor Benjamin K. Sovacool and Professor Jinsoo Kim, the combined externalities for the energy and transport sectors worldwide is an estimated average of $24.662 trillion - the equivalent to 28.7% of global Gross Domestic Product.

The study found that the true cost of coal should be more than twice as high as current prices when factoring in the currently unaccounted ...

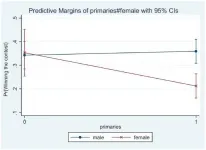

A study by two researchers at the UPF Department of Political and Social Sciences (DCPIS) has examined the effect of selecting party leaders by direct vote by the entire membership (a process known in southern Europe as "primaries" and in English-speaking countries as "one-member-one -vote", OMOV) on the likelihood of a woman winning a leadership competition against male rivals.

Javier Astudillo and Andreu Paneque, a tenured lecturer and PhD with the DCPIS, respectively, and members of the Institutions and Political Actors Research Group, are the authors of the article published recently in the journal ...