(Press-News.org) New research has revealed that the diets of early lizards and snakes, which lived alongside dinosaurs around 100 million years ago, were more varied and advanced than previously thought.

The study, led by the University of Bristol and published in Royal Society Open Science, showed lizards, snakes, and mosasaurs in the Cretaceous period already had the full spectrum of diet types, including flesh-eating and plant-based, which they have today.

There are currently some 10,000 species of lizards and snakes, known collectively as squamates. It was originally understood their great diversity was acquired only after the extinction of dinosaurs, but the findings demonstrate for the first time that squamates had modern levels of dietary specialisation 100 million years ago.

Fossils of lizards and snakes are quite rare in the Mesozoic, the age of dinosaurs and reptiles. This could simply be because their skeletons are small and delicate so hard to preserve, or it could show that lizards and snakes were in fact quite rare in the first half of their history.

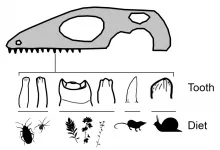

The researchers studied 220 Mesozoic squamates, comprising lizards, snakes and mosasaurs, a group of extinct large marine reptiles. They measured their jaws and teeth and allocating them to dietary classes by comparison with modern forms. Some have long peg-like teeth and feed on insects, others have flat teeth used for chopping plant food. Predators have sharp, pointed teeth, and snakes have hooked teeth to grasp their prey.

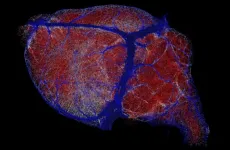

All the fossil forms were allocated to one of eight feeding categories, and then their diversity through time was assessed. To the researchers' surprise, it turned out that the rather sparse Cretaceous squamates included examples of all modern feeding strategies.

"We don't know for sure how diverse squamates were in the Cretaceous," said lead author Dr Jorge Herrera-Flores, who is now a Research Fellow at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

"But we do know they had already achieved the full modern-type diversity of feeding modes by 100 million years ago, in the middle of the Cretaceous. Before that, squamates had already existed for more than 100 million years, but they seemed to be mainly insect-eaters up to that point."

"Studying teeth and jaws provides excellent insights into dietary and ecological variety," said co-author Dr Tom Stubbs, Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol School of Earth Sciences. "Fossil teeth and jaws give us the best insight into squamate evolution in the past. It would be easy to read the fossil record wrongly because of incomplete preservation. However, more fossil finds could only increase the number of feeding modes we identify in the Cretaceous, not reduce them."

The explanation for this early rush of dietary experimentation may be related to diversification in other areas. For instance, at this point in the Cretaceous, flowering plants had just begun to flourish and were already transforming ecosystems on land, while squamates also prevailed in the oceans.

"The Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution made forests more complex," said co-author Professor Michael Benton, Professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the School of Earth Sciences. "The new flowering plants provided opportunities for insects and other creepy crawlies to feed on leaves, pollen and nectar, and to hide in the canopy. It's likely this burst of diversity gave a stimulus to mammals, birds and squamates, all of which diversified about this time, probably feeding on the insects, spiders and other bugs, as well as on the new plant food."

The new work does not provide the single reason why squamates are so diverse today - nearly as diverse as birds. However, it shows that their ancestors had already explored all the likely feeding niches 100 million years ago before the dinosaurs died out.

INFORMATION:

Paper

'Ecomorphological diversification of squamates in the Cretaceous' by Herrera-Flores JA, Stubbs TL, Benton MJ in Royal Society Open Science

Notes to editors

Link to paper when live: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201961 (advance embargoed copies available on request)

Images

Caption: Modern and fossil lizards have many different tooth types. These are linked to different diets and can be used to assess dietary diversity through time in fossils. Credit: Tom Stubbs

https://fluff.bris.ac.uk/fluff/u3/oc20541/VmrJMUtrpx1ZElD16d0xCwzcM/

Caption: Jaw shape variety can be visualised in 'morpho-spaces' and linked to diets. Credit: Tom Stubbs

https://fluff.bris.ac.uk/fluff/u1/oc20541/ErXbdnoz1b6Uv9G7LFrePgzce/

Caption: Image of lizard fossil. Credit: Jorge Herrera Flores.

https://fluff.bris.ac.uk/fluff/u2/oc20541/Qo2MwrbI_W51aHGzi_v4dQzcB/

Caption: Image of Mosasaur jaws and teeth. Credit: Tom Stubbs

https://fluff.bris.ac.uk/fluff/u2/oc20541/zXUOLS3OsXFxTZGpNReE4wzck/

Caption: Image of a Caiman lizard. Credit: Smithsonian archives

https://fluff.bris.ac.uk/fluff/u1/oc20541/iCiUcb5b8VrqghzdXYM0PQzcx/

Patients with type 2 diabetes that were treated with a weekly injection of the breakthrough drug Semaglutide were able to achieve an average weight loss of nearly 10kg, according to a new study published in The Lancet today.

Led by Melanie Davies, Professor of Diabetes Medicine at the University of Leicester and the Co-Director of the Leicester Diabetes Centre, the study showed that two thirds of patients with type 2 diabetes that were treated with weekly injections of a 2.4mg dose of Semaglutide were able to lose at least 5% of their body weight and achieved significant improvement in blood glucose control.

More than a quarter of patients were able to ...

Pregnant patients in Colorado may be told about parenting and adoption, but not abortion. This is according to a new study led by Kate Coleman-Minahan of the University of Colorado College of Nursing published in the END ...

Our brains are non-stop consumers. A labyrinth of blood vessels, stacked end-to-end comparable in length to the distance from San Diego to Berkeley, ensures a continuous flow of oxygen and sugar to keep our brains functioning at peak levels.

But how does this intricate system ensure that more active parts of the brain receive enough nourishment versus less demanding areas? That's a century-old problem in neuroscience that scientists at the University of California San Diego have helped answer in a newly published study.

Studying the brains of mice, a team of researchers led by Xiang Ji, David Kleinfeld and their colleagues has deciphered the question of brain energy consumption and blood vessel density through newly developed maps that detail ...

When you think about your carbon footprint, what comes to mind? Driving and flying, probably. Perhaps home energy consumption or those daily Amazon deliveries. But what about watching Netflix or having Zoom meetings? Ever thought about the carbon footprint of the silicon chips inside your phone, smartwatch or the countless other devices inside your home?

Every aspect of modern computing, from the smallest chip to the largest data center comes with a carbon price tag. For the better part of a century, the tech industry and the field of computation ...

Imagine you're driving up a hill toward a traffic light. The light is still green so you're tempted to accelerate to make it through the intersection before the light changes. Then, a device in your car receives a signal from the controller mounted on the intersection alerting you that the light will change in two seconds -- clearly not enough time to beat the light. You take your foot off the gas pedal and decelerate, saving on fuel. You feel safer, too, knowing you didn't run a red light and potentially cause a collision in the intersection.

Connected and automated vehicles, which can interact vehicle to vehicle (V2V) and between vehicles and roadway ...

Type 2 diabetes, once considered an adult disease, is increasingly causing health complications among American youth. A research review published in the Journal of Osteopathic Medicine suggests physicians should work to more aggressively prevent pediatric diabetes.

Because few pediatric Type 2 diabetes treatment options are available, prevention is unusually important. To improve health outcomes, the paper's authors recommend physicians conduct regular screenings of children and adolescents, adopt a high level of suspicion, and intervene early and often with families who have children at risk for prediabetes and T2 diabetes.

"Pediatric type 2 diabetes is more progressive and aggressive than adult-onset Type 2 diabetes," ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: Several articles were published online ahead of print

for GSA Bulletin in February. Topics include earthquake cycles in

southern Cascadia, fault dynamics in the Gulf of Mexico, debris flow after

wildfires, the assembly of Rodinia, and the case for no ring fracture in

Mono basin.

Jurassic evolution of the Qaidam Basin in western China: Constrained by

stratigraphic

succession, detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotope analysis

Tao Qian; Zongxiu Wang; Yu Wang; Shaofeng Liu; Wanli Gao ...

Abstract:

The formation and evolution of an intracontinental basin triggered via the

subduction or collision of plates at continental margins can record

intracontinental tectonic processes. As a typical ...

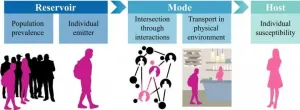

In the 1995 movie "Outbreak," Dustin Hoffman's character realizes, with appropriately dramatic horror, that an infectious virus is "airborne" because it's found to be spreading through hospital vents.

The issue of whether our real-life pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2, is "airborne" is predictably more complex. The current body of evidence suggests that COVID-19 primarily spreads through respiratory droplets - the small, liquid particles you sneeze or cough, that travel some distance, and fall to the floor. But consensus is mounting that, under the right circumstances, smaller floating particles called aerosols can carry the virus over longer distances and remain ...

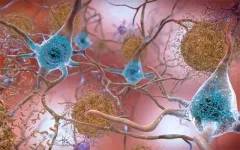

Amyloid plaques are pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease (AD) -- clumps of misfolded proteins that accumulate in the brain, disrupting and killing neurons and resulting in the progressive cognitive impairment that is characteristic of the widespread neurological disorder.

In a new study, published March 2, 2021 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and elsewhere have identified a new drug that could prevent AD by modulating, rather than inhibiting, a key enzyme involved ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- When quantum computers become more powerful and widespread, they will need a robust quantum internet to communicate.

Purdue University engineers have addressed an issue barring the development of quantum networks that are big enough to reliably support more than a handful of users.

The method, demonstrated in a paper published in Optica, could help lay the groundwork for when a large number of quantum computers, quantum sensors and other quantum technology are ready to go online and communicate with each other.

The team deployed a programmable switch to adjust how much data goes to each ...