(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Humans have made a remarkable impact on the planet, from clearing forests for agriculture and urbanization to altering the chemistry of the atmosphere with fossil fuels. Now, a new study in the journal Nature reveals for the first time the extent of human impact on the global water cycle.

The study used NASA's Ice, Cloud and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2) to assemble the largest ever dataset of seasonal water levels in more than 227,000 lakes, ponds and reservoirs worldwide. The data reveal that even though human-managed reservoirs comprise only a small percentage of all water bodies, they account for 57% of the total seasonal water storage changes globally.

"We tend to think of the water cycle as a purely natural system: Rain and snowmelt run into rivers, which run to the ocean where evaporation starts the whole cycle again," said Sarah Cooley, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University who launched the research project while a graduate student at Brown University. "But humans are actually intervening substantially in that cycle. Our work demonstrates that humans are responsible for a majority of the seasonal surface water storage variability on Earth."

Cooley led the work with Laurence Smith, a professor of environmental sciences at Brown, and Johnny Ryan, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society.

The researchers say the study provides a critical baseline for tracking the global hydrological cycle as climate change and population growth put new stresses on freshwater resources.

An extraordinary dataset

Launched into orbit in 2018, ICESat-2's primary mission is to track changes in the thickness and elevation of ice sheets around the world. It does so with a laser altimeter, which uses pulses of light to measure elevation to an accuracy of 25 millimeters. Cooley, who has experience using satellites to study water levels in Arctic lakes, was interested in bringing the satellite's precise measurement capacity to bear on lake levels worldwide.

Cooley says that ICESat-2's laser altimeter has far greater resolution than instruments used to measure water levels in the past. That made it possible to gather a large, precise dataset that included small ponds and reservoirs.

"With older satellites, you have to average results over a large area, which limits observations to only the world's largest lakes," Cooley said. "ICESat has a small footprint, so we can get levels for small lakes that we couldn't get close to before. That was important for understanding global water dynamics, since most lakes and reservoirs are pretty small."

From October 2018 to July 2020, the satellite measured water levels in 227,386 bodies of water, ranging in size from the American Great Lakes to ponds with areas less than one tenth of a square mile. Each water body was observed at different times of year to track changes in water levels. The researchers cross-referenced the water bodies they observed with a database of reservoirs worldwide to identify which water bodies were human-controlled and which were natural.

While countries like the U.S. and Canada gauge reservoir levels and make that information publicly available, many countries don't publish such data. And very few non-reservoir lakes and ponds are gauged at all. So there was no way to do this analysis without the precise satellite observations, the researchers said.

Commandeering the water cycle

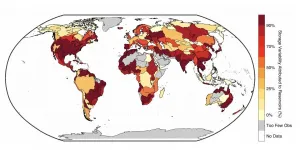

The study found that while natural lakes and ponds varied seasonally by an average of .22 meters, human-managed reservoirs varied by .86 meters. Added together, the much larger variation in reservoirs compared to natural lakes means that reservoirs account for 57% of the total variation. In some places, however, human influence was even stronger than that. For example, in arid regions like the Middle East, American West, India and Southern Africa, variability attributed to human control surges to 90% and above.

"Of all the volume changes in freshwater bodies around the planet -- all the floods, droughts and snowmelt that push lake levels up and down -- humans have commandeered almost 60% of that variability," Smith said. "That's a tremendous influence on the water cycle. In terms of human impact on the planet, this is right up there with impacts on land cover and atmospheric chemistry."

As the first global quantification of human impacts on the water cycle, the results will provide a crucial baseline for future research on how the impacts affect ecosystems around the world, the researchers say.

In a separate study published recently in Geophysical Research Letters, the research team was able to use ICESat-2 data to shed light on how reservoir water is being used. The study showed that in places like the Middle East, reservoir levels tend to be lower in summer and higher in the winter. That suggests that water is being released in the dry season for irrigation and drinking water. In contrast, the trend in places like Scandinavia was the opposite. There, water is released in the winter to make hydroelectric power for heating.

"This was an exploratory analysis to see if we can use remote sensing to understand how reservoirs are being used at a global scale," Ryan said.

Smith says he expects satellites to play an increasing role in study of the Earth's water cycle. For the past few years, he has been working with NASA on the Surface Water and Ocean Topography mission, which will be dedicated entirely to this kind of research.

"I think within the next three years we are going to see an explosion of high-quality satellite hydrology data, and we're going to have a much better idea of what's going on with water all over the planet," Smith said. "That will have implications for security, trans-boundary water agreements, forecasting crop futures and more. We're right on the edge of a new understanding of our planet's hydrology."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the NASA Studies with ICESat-2 Program (80NSSC20K0963) and the NASA Surface Water and Ocean Topography mission (80NSSC20K1144S).

A team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Cardiff University say they have found the strongest evidence yet of a "migration gene" in birds.

The team identified a single gene associated with migration in peregrine falcons by tracking them via satellite technology and combining this with genome sequencing.

They say their findings add further evidence to suggest genetics has a strong role to play in the distance of migration routes.

The study, published today in the journal Nature, also looks at the predicted effect of climate change on migration - and how this might interact with evolutionary factors.

The researchers tagged 56 Arctic peregrine falcons and tracked their journeys by satellite, following their annual flight distances and directions in detail.

They found the studied ...

At the beginning of an immune response, a molecule known to mobilize immune cells into the bloodstream, where they home in on infection sites, rapidly shifts position, a new study shows. Researchers say this indirectly amplifies the attack on foreign microbes or the body's own tissues.

Past studies had shown that the immune system regulates the concentration of the molecule, sphingosine 1 phosphate (S1P), in order to draw cells to the right locations. The targeted cells have proteins on their surface that are sensitive to levels of this molecule, enabling them to follow the molecule's "trail," researchers say. S1P concentration gradients, for instance, can guide immune T cells to either stay in lymph nodes, connected glands in which these cells mature, or move into blood ...

New research shows 64 countries cut their fossil CO2 emissions during 2016-2019, but the rate of reduction needs to increase tenfold to meet the Paris Agreement aims to tackle climate change.

This first global stocktake by researchers at the University of East Anglia (UEA), Stanford University and the Global Carbon Project examined progress in cutting fossil CO2 emissions since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015. Their results show the clear need for far greater ambition ahead of the important UN climate summit in Glasgow in November (COP26).

The annual cuts of 0.16 billion tonnes of CO2 are only 10 ...

SPOKANE, Wash. - The researchers' findings showed that participants who were given A low-cost, easy-to-administer intervention that uses small prizes and other incentives to reward alcohol abstinence can serve as an effective tool to reduce alcohol use among American Indian and Alaska Native communities, new research suggests.

Published today in JAMA Psychiatry, the study tested a culturally adapted version of an intervention known as contingency management in American Indian and Alaska Native adults diagnosed with alcohol dependence, a severe form of ...

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, there was a 34% increase in alcohol withdrawal (AW) rates among hospitalized patients at ChristianaCare, according to a research letter published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study is believed to be the first to quantify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol withdrawal among hospitalized patients.

The retrospective study conducted at ChristianaCare, one of the largest health systems in the mid-Atlantic region, found that the rate of alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients was consistently higher in 2020 compared to both 2019 and the average of 2019 and 2018.

"Our findings are relevant nationally and serve as a clarion call to alert ...

What The Study Did: Whether alcohol withdrawal rates among hospitalized patients with alcohol use disorder increased during the COVID-19 pandemic was examined in this study.

Authors: Ram A. Sharma M.D., of Christiana Care in ,Newark, Delaware, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0422)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

What The Study Did: Researchers in this randomized clinical trial examined the effectiveness of incentives offered for laboratory-confirmed abstinence from alcohol among American Indian and Alaska Native adults diagnosed with alcohol dependence.

Authors: Michael G. McDonell, Ph.D., of Washington State University in Spokane, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4768)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding and support disclosures. Please see the article for additional ...

What The Study Did: This study combined the results of 27 studies with 10,000 participants to investigate the association between cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and high blood pressure and cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia.

Authors: Christoph U. Correll, M.D., of the Zucker Hillside Hospital in Glen Oaks, New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0015)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

Water levels in the world's ponds, lakes and human-managed reservoirs rise and fall from season to season. But until now, it has been difficult to parse out exactly how much of that variation is caused by humans as opposed to natural cycles.

Analysis of new satellite data published March 3 in Nature shows fully 57 percent of the seasonal variability in Earth's surface water storage now occurs in dammed reservoirs and other water bodies managed by people.

"Humans have a dominant effect on Earth's water cycle," said lead author Sarah Cooley, a postdoctoral scholar ...

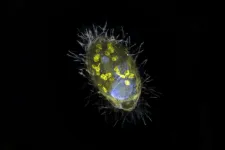

Researchers from Bremen, together with their colleagues from the Max Planck Genome Center in Cologne and the aquatic research institute Eawag from Switzerland, have discovered a unique bacterium that lives inside a unicellular eukaryote and provides it with energy. Unlike mitochondria, this so-called endosymbiont derives energy from the respiration of nitrate, not oxygen. "Such partnership is completely new," says Jana Milucka, the senior author on the Nature. "A symbiosis that is based on respiration and transfer of energy is to this date unprecedented".

In general, among eukaryotes, symbioses ...