Humans drive most of the ups and downs in freshwater storage at Earth's surface

2021-03-03

(Press-News.org) Water levels in the world's ponds, lakes and human-managed reservoirs rise and fall from season to season. But until now, it has been difficult to parse out exactly how much of that variation is caused by humans as opposed to natural cycles.

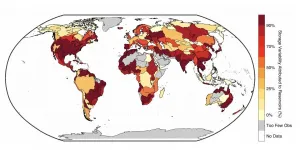

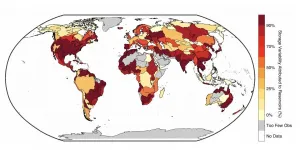

Analysis of new satellite data published March 3 in Nature shows fully 57 percent of the seasonal variability in Earth's surface water storage now occurs in dammed reservoirs and other water bodies managed by people.

"Humans have a dominant effect on Earth's water cycle," said lead author Sarah Cooley, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth).

The scientists used 22 months of data from NASA's ICESat-2, which launched in October 2018 and collected highly accurate measurements for 227,386 water bodies worldwide, including some smaller than a soccer field. "Previous satellites have not been able to come anywhere close to that," said Cooley, who performed most of the analysis on a laptop, stationed on her parents' couch, after coronavirus restrictions canceled her scheduled field season in Greenland. "I needed to find a project I could work on remotely," she said.

Cooley and colleagues found that water levels in Earth's lakes and ponds change about 8.6 inches between the wet and dry seasons. Meanwhile, human-managed reservoirs fluctuate by nearly four times that amount, rising and falling by an average of 2.8 feet from season to season.

The western United States, southern Africa and the Middle East rank among regions with the highest reservoir variability, averaging 6.5 feet to 12.4 feet. They also have some of the strongest human influence, with managed reservoirs accounting for 99 percent or more of the seasonal variations in surface water storage. "That's indicative that these are places that are water stressed where careful water management is really important," Cooley said. In some other basins, humans influence less than 10 percent of the variability. "Sometimes those basins are next to each other because even within the same region, a combination of economic and environmental factors mean humans make different choices about how to manage surface water storage."

While water levels naturally rise and fall throughout the year, this seasonal variation is exaggerated in dammed reservoirs where more water is stored in the rainy season and diverted when it's dry. "There are a lot of ways in which this is bad for the environment," Cooley said, ranging from harm to fish populations to potential increases in emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

The implications of regulating water levels in reservoirs are not black and white, however. "A lot of this variability is associated with either producing hydroelectric power or irrigation. It can also be protective against flooding," Cooley said. Human influence is generally stronger in more densely populated areas. However, sparsely populated areas with large hydropower dams, such as Northern Quebec and Eastern Siberia, are notable exceptions.

The new work offers an important baseline for future research, as economic development, population growth and climate change continue to strain water resources around the world, and as more satellites begin tracking human modifications to Earth's water cycle. "Our ability to observe the water cycle is undergoing a revolution," Cooley said. While the current study offers a 22-month snapshot in time, she said, it will soon become possible to use the same methods to understand year-to-year variability and to predict longer-term trends. "This is a first global quantification, but it won't be the last."

INFORMATION:

Cooley is also affiliated with the University of Oregon. Co-authors Jonathan Ryan and Laurence Smith are affiliated with the University of Oregon and Brown University.

This research was funded by NASA. The authors received support from NSF, the Stanford Science Fellows program and the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-03

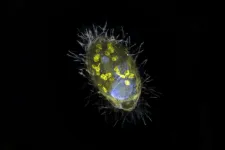

Researchers from Bremen, together with their colleagues from the Max Planck Genome Center in Cologne and the aquatic research institute Eawag from Switzerland, have discovered a unique bacterium that lives inside a unicellular eukaryote and provides it with energy. Unlike mitochondria, this so-called endosymbiont derives energy from the respiration of nitrate, not oxygen. "Such partnership is completely new," says Jana Milucka, the senior author on the Nature. "A symbiosis that is based on respiration and transfer of energy is to this date unprecedented".

In general, among eukaryotes, symbioses ...

2021-03-03

An international research group led by the University of Basel has developed a promising strategy for therapeutic cancer vaccines. Using two different viruses as vehicles, they administered specific tumor components in experiments on mice with cancer in order to stimulate their immune system to attack the tumor. The approach is now being tested in clinical studies.

Making use of the immune system as an ally in the fight against cancer forms the basis of a wide range of modern cancer therapies. One of these is therapeutic cancer vaccination: following diagnosis, specialists set about determining which components of the tumor could function as an identifying feature for the immune system. The patient is then administered ...

2021-03-03

The universe was created by a giant bang; the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, and then it started to expand. The expansion is ongoing: it is still being stretched out in all directions like a balloon being inflated.

Physicists agree on this much, but something is wrong. Measuring the expansion rate of the universe in different ways leads to different results.

So, is something wrong with the methods of measurement? Or is something going on in the universe that physicists have not yet discovered and therefore have not taken into account?

It could very well be the latter, according to several physicists, i.a. Martin S. Sloth, Professor of Cosmology at University of Southern Denmark (SDU).

In a new scientific article, he and his SDU ...

2021-03-03

A new software tool allows researchers to quickly query datasets generated from single-cell sequencing. Users can identify which cell types any combination of genes are active in. Published in Nature Methods on 1st March, the open-access 'scfind' software enables swift analysis of multiple datasets containing millions of cells by a wide range of users, on a standard computer.

Processing times for such datasets are just a few seconds, saving time and computing costs. The tool, developed by researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, can be used much like a search engine, as users can input free text as well as gene names.

Techniques to sequence the genetic material from an individual cell have advanced ...

2021-03-03

Information is encoded in data. This is true for most aspects of modern everyday life, but it is also true in most branches of contemporary physics, and extracting useful and meaningful information from very large data sets is a key mission for many physicists.

In statistical mechanics, large data sets are daily business. A classic example is the partition function, a complex mathematical object that describes physical systems at equilibrium. This mathematical object can be seen as made up by many points, each describing a degree of freedom of a physical system, that is, the minimum number of data that can describe all of its properties.

An ...

2021-03-03

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Boron, a metalloid element that sits next to carbon in the periodic table, has many traits that make it potentially useful as a drug component. Nonetheless, only five FDA-approved drugs contain boron, largely because molecules that contain boron are unstable in the presence of molecular oxygen.

MIT chemists have now designed a boron-containing chemical group that is 10,000 times more stable than its predecessors. This could make it possible to incorporate boron into drugs and potentially improve the drugs' ability to bind their targets, the researchers say.

"It's an entity ...

2021-03-03

Judging by its massive, bone-crushing teeth, gigantic skull and powerful jaw, there is no doubt that the Anteosaurus, a premammalian reptile that roamed the African continent 265 to 260 million years ago - during a period known as the middle Permian - was a ferocious carnivore.

However, while it was previously thought that this beast of a creature - that grew to about the size of an adult hippo or rhino, and featuring a thick crocodilian tail - was too heavy and sluggish to be an effective hunter, a new study has shown that the Anteosaurus would have been able to outrun, track down and kill its prey effectively.

Despite its name and fierce appearance, ...

2021-03-03

When the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland erupted in April 2010, air traffic was interrupted for six days and then disrupted until May. Until then, models from the nine Volcanic Ash Advisory Centres (VAACs) around the world, which aimed at predicting when the ash cloud interfered with aircraft routes, were based on the tracking of the clouds in the atmosphere. In the wake of this economic disaster for airlines, ash concentration thresholds were introduced in Europe which are used by the airline industry when making decisions on flight restrictions. However, a team of researchers, ...

2021-03-03

The planet Mars has no global magnetic field, although scientists believe it did have one at some point in the past. Previous studies suggest that when Mars' global magnetic field was present, it was approximately the same strength as Earth's current field. Surprisingly, instruments from past Mars missions, both orbiters and landers, have spotted patches on the planet's surface that are strongly magnetized--a property that could not have been produced by a magnetic field similar to Earth's, assuming the rocks on both planets are similar.

Ahmed AlHantoobi, an intern working with Northern Arizona University planetary scientists, assistant professor Christopher Edwards and postdoctoral ...

2021-03-03

PITTSBURGH, March 3, 2021 - Women who experience an accelerated accumulation of abdominal fat during menopause are at greater risk of heart disease, even if their weight stays steady, according to a University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health-led analysis published today in the journal Menopause.

The study--based on a quarter century of data collected on hundreds of women--suggests that measuring waist circumference during preventive health care appointments for midlife women could be an early indicator of heart disease risk beyond the widely used body mass index (BMI)--which is a calculation of weight vs. height.

"We need to shift gears on how we think about heart disease risk in women, particularly as they approach and go through menopause," said senior ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Humans drive most of the ups and downs in freshwater storage at Earth's surface