Scientists discover how microorganisms evolve cooperative behaviors

Just-published research provides new window to understand key roles of interspecies interactions in industrial applications, and in the health and disease of humans, animals and plants

2021-03-04

(Press-News.org) Interspecies interactions are the foundation of ecosystems, from soil to ocean to human gut. Among the many different types of interactions, syntrophy is a particularly important and mutually beneficial interspecies interaction where one partner provides a chemical or nutrient that is consumed by the other in exchange for a reward.

Syntrophy plays an essential role in global carbon cycles by mediating the conversion of organic matter to methane, which is about 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas and is a source of sustainable energy. And in the human gut, trillions of microbial cells also interact with each other and other species to modulate the physiology of their human host.

Therefore, deciphering the nature, evolution, and mechanism of syntrophic interspecies interactions is fundamental to understand and manipulate microbial processes, bioenergy production and environmental sustainability.

However, our understanding of what drives these interactions, how they evolve and how their disruption may lead to disease or ecosystem instability, is not well understood.

ISB researchers and collaborators aimed to tackle these fundamental questions to shed light on how interspecies interactions - specifically, cooperation - arise, evolve and are maintained. Their results provide a new window to understand the key roles of these interactions in industrial applications, and in the health and disease of humans, animals and plants.

The study builds on the prior work on syntrophic interactions among two microbes - Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Dv) and Methanococcus maripaludis (Mm) - that coexist in diverse environments (gut, soil, etc.) and play a central role in an important step in biogeochemical carbon cycling.

With a multidisciplinary approach cutting across systems biology, microbiology, evolutionary biology and other disciplines, researchers analyzed massive amounts of genome sequence data generated from more than 400 samples. They investigated the temporal and combinatorial patterns in which mutations accumulated in both organisms over 1,000 generations, mapped lineages through high resolution single cell sequencing, and characterized the fitness and cooperativity of pairings of their individual isolates.

The team uncovered striking evidence that mutations accumulated during evolution generate positive genetic interactions among rare individuals of a microbial community. These genetic interactions increase cooperativity within these rare microbial assemblages, enabling their persistence at very low frequency within a larger productive population. In addition, researchers discovered one of the first examples of parallel evolution, i.e., accumulation of mutations in similar genes across independently evolving populations, underlying the evolution of both organisms in a mutualistic community.

"This study is a significant step in understanding and manipulating early adaptive events in evolution of mutualistic interactions with a wide range of applications for biotechnology, medicine and environment," said Dr. Serdar Turkarslan, senior research scientist in ISB's Baliga Lab and lead author of a paper recently published in The ISME Journal.

These discoveries are of great interest because they explain how diverse microbial populations co-exist in dynamically changing environments, such as in reactors, lake sediments and the human gut. Moreover, the study incorporates multiscale systems analysis of diverse kinds of longitudinal datasets and experimental testing of hypotheses to characterize a complex phenomenon that emerges from interactions at the genetic level between two members of a microbial community.

"The methodologies, insights and resources generated by this study will have wide applicability to the study of other interspecies interactions and evolutionary phenomena," said ISB Professor, Director and Senior Vice President Dr. Nitin Baliga, a co-corresponding author of the paper. "One of the fundamental questions of biology is whether we can predict and modulate interspecies interactions such as the ones between the pathogens and their host environment. If we understand what are the genes that drive interaction of pathogens with the host, we can design therapies to alter the host microenvironment and permissibility of infection, or by directly changing pathogen recognition. For industrial applications, we can quickly screen for the most cooperative mutations across different microbial consortia to facilitate production of public goods."

INFORMATION:

About ISB

Institute for Systems Biology (ISB) is a collaborative and cross-disciplinary non-profit biomedical research organization based in Seattle. We focus on some of the most pressing issues in human health, including aging, brain health, cancer, COVID-19, sepsis, as well as many infectious diseases. Our science is translational, and we champion sound scientific research that results in real-world clinical impacts. ISB is an affiliate of Providence, one of the largest not-for-profit health care systems in the United States. Follow us online at http://www.isbscience.org, and on Facebook and Twitter.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-04

Intelligent holographic nanostructures on CMOS sensors for energy-efficient AI security schemes

Today, machine learning permeates our everyday life, with millions of users every day unlocking their phones through facial recognition or passing through AI-enabled automated security checks at airports and train stations. These tasks are possible thanks to sensors that collect optical information to feed it to a neural network in a computer. Imagine to empower the sensors in the devices you use every day to perform artificial intelligence functions without a computer - as simply as putting glasses on them.

The integrated holographic perceptrons developed by a research team at University of Shanghai for Science and Technology led ...

2021-03-04

Nairobi/Paris, 4 March 2021 - An estimated 931 million tonnes of food, or 17% of total food available to consumers in 2019, went into the waste bins of households, retailers, restaurants and other food services, according to new UN research conducted to support global efforts to halve food waste by 2030.

The weight roughly equals that of 23 million fully-loaded 40-tonne trucks -- enough bumper-to-bumper to circle the Earth 7 times.

The Food Waste Index Report 2021, from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and partner organization WRAP, looks at food waste that occurs in retail outlets, restaurants and homes - ...

2021-03-04

People with higher incomes tend to feel prouder, more confident and less afraid than people with lower incomes, but not necessarily more compassionate or loving, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

In a study of data from 162 countries, researchers found consistent evidence that higher income predicts whether people feel more positive "self-regard emotions," including confidence, pride and determination. Lower income had the opposite effect, and predicted negative self-regard emotions, such as sadness, fear and shame. The research was published online in the journal Emotion. ...

2021-03-04

A group of researchers, spanning six universities and three continents, are sounding the alarm on a topic not often discussed in the context of conservation--misinformation.

In a recent study published in FACETS, the team, including Dr. Adam Ford, Canada Research Chair in Wildlife Restoration Ecology, and Dr. Clayton Lamb, Liber Ero Fellow, both based in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science, explain how the actions of some scientists, advocacy groups and the public are eroding efforts to conserve biodiversity.

"Outcomes, not intentions, should be the basis for how we view success in conservation," says Dr. Ford.

"Misinformation related to vaccines, climate change, and links between smoking ...

2021-03-04

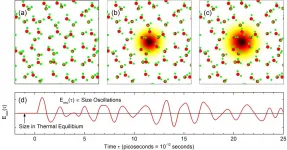

Ionization of water molecules by light generates free electrons in liquid water. After generation, the so-called solvated electron is formed, a localized electron surrounded by a shell of water molecules. In the ultrafast localization process, the electron and its water shell display strong oscillations, giving rise to terahertz emission for tens of picoseconds.

Ionization of atoms and molecules by light is a basic physical process generating a negatively charged free electron and a positively charged parent ion. If one ionizes liquid water, the free electron undergoes a sequence of ultrafast processes by which it loses energy and eventually localizes at a new site in ...

2021-03-04

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina--UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center researchers have successfully used an experimental safety switch, incorporated as part of a chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, a type of immunotherapy, to reduce the severity of treatment side effects that sometimes occur. This advance was seen in a patient enrolled in a clinical trial using CAR-T to treat refractory acute B-cell leukemia. It demonstrates a proof-of-principle for possible expanded use of CAR-T immunotherapy paired with the safety switch.

The researchers published their findings in the journal Blood as an ahead-of-print publication.

With CAR-T therapy, T-cells from a patient's immune system ...

2021-03-04

The human genome contains roughly three million letters. On average, the genome sequences of any two people differ from each other by about one in every 1,000 letters. Yet different variants occur, from substituted letters to entire missing sections of DNA. Scientists from the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) and the Regensburg Center for Interventional Immunology (RCI) have teamed up with Icelandic researchers to develop software that reliably and quickly identifies large deletions in ten-thousands of genomes simultaneously. The researchers have now published their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

The human genome contains roughly three million letters ...

2021-03-04

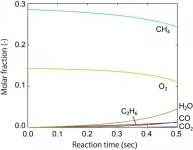

Japanese researchers have developed a simulation method to theoretically estimate the performance of heterogeneous catalyst by combining first-principles calculation (1) and kinetic calculation techniques. Up to now, simulation studies mainly focused on a single or limited number of reaction pathways, and it was difficult to estimate the efficiency of a catalytic reaction without experimental information.

Atsushi Ishikawa, Senior Researcher, Center for Green Research on Energy and Environmental Materials, National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS), performed computation of reaction kinetic information from first-principles calculations based on quantum mechanics, and developed methods and programs to carry out kinetic simulations ...

2021-03-04

The speed at which we produce facial expressions plays an important role in our ability to recognise emotions in others, according to new research at the University of Birmingham.

A team in the University's School of Psychology carried out research which showed that people tend to produce happy and angry expressions more rapidly, while sad expressions are produced more slowly.

The team found that our ability to form judgements about people's facial expressions has close links with the speeds at which those expressions are produced and is also closely related to the ways in which we would produce those expressions ourselves. The study is published in Emotion.

"Being able to recognise and interpret ...

2021-03-04

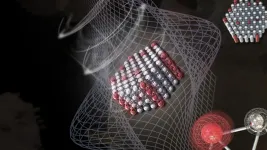

Much like the Jedis in Star Wars use 'the force' to control objects from a distance, scientists can use light or 'optical force' to move very small particles.

The inventors of this ground-breaking laser technology, known as 'optical tweezers', were awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in physics.

Optical tweezers are used in biology, medicine and materials science to assemble and manipulate nanoparticles such as gold atoms. However, the technology relies on a difference in the refractive properties of the trapped particle and the surrounding environment.

Now scientists have discovered a new technique that allows them to manipulate particles that have the same refractive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists discover how microorganisms evolve cooperative behaviors

Just-published research provides new window to understand key roles of interspecies interactions in industrial applications, and in the health and disease of humans, animals and plants