(Press-News.org) COVID-19 is only the latest infectious disease to have had an outsized impact on human life. A new study employing ancient human DNA reveals how tuberculosis has affected European populations over the past 2,000 years, specifically the impact that disease has had on the human genome. This work, which publishes March 4 in the American Journal of Human Genetics, has implications for studying not only evolutionary genetics, but also how genetics can influence the immune system.

"Present-day humans are the descendants of those who have survived many things--climate changes and big epidemics, including the Black Death, Spanish flu, and tuberculosis," says senior author Lluis Quintana-Murci of the Institut Pasteur in France. "This work uses population genetics to dissect how natural selection has acted on our genomes."

This research focused on a variant of the gene TYK2, called P1104A, which first author Gaspard Kerner had previously found to be associated with an increased risk of becoming ill after infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis when the variant is homozygous. (TYK2 has been implicated in immune function through its effect on interferon signaling pathways.) Kerner, a PhD student studying genetic diseases at the Imagine Institute of Paris University, began collaborating with Quintana-Murci, an expert in evolutionary genomics, to study the genetic determinants of human tuberculosis in the context of evolution and natural selection.

Using a large dataset of more than 1,000 European ancient human genomes, the investigators found that the P1104A variant first emerged more than 30,000 years ago. Further analysis revealed that the frequency of the variant drastically decreased about 2,000 years ago, around the time that present-day forms of infectious Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains became prevalent. The variant is not associated with other infectious bacteria or viruses.

"If you carry two copies of this variant in your genome and you encounter Mycobacterium tuberculosis, you are very likely to become sick," Kerner says. "During the Bronze Age, this variant was much more frequent, but we saw that it started to be negatively selected at a time that correlated with the start of the tuberculosis epidemic in Europe."

"The beauty of this work is that we're using a population genetics approach to reconstruct the history of an epidemic," Quintana-Murci explains. "We can use these methods to try to understand which immune gene variants have increased the most over the last 10,000 years, indicating that they are the most beneficial, and which have decreased the most, due to negative selection."

He adds that this type of research can be complementary to other types of immunology studies, such as those performed in the laboratory. Moreover, both researchers say these tools can be used to study the history and implications of many different genetic variants for multiple infectious diseases.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur, the College de France, the Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), the French Government's Investissement d'Avenir program, Laboratoires d'Excellence "Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases" and "Milieu Interieur,", the Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale, the Fondation Allianz-Institut de France, and the Fondation de France. Kerner was supported by the Imagine Institute with the grant "Imagine Thesis Award."

American Journal of Human Genetics, Kerner et al.: "Human ancient DNA analyses reveal the high burden of tuberculosis in Europeans over the last 2,000 years" https://www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297(21)00051-3

The American Journal of Human Genetics (@AJHGNews), published by Cell Press for the American Society of Human Genetics, is a monthly journal that provides a record of research and review relating to heredity in humans and to the application of genetic principles in medicine and public policy, as well as in related areas of molecular and cell biology. Visit http://www.cell.com/ajhg. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact press@cell.com.

To succeed in mating, many male frogs sit in one place and call to their potential mates. But this raises an important question familiar to anyone trying to listen to someone talking at a busy cocktail party: how does a female hear and then find a choice male of her own species among all the irrelevant background noise, including the sound of other frog species? Now, researchers reporting March 4 in the journal Current Biology have found that they do it thanks to a set of lungs that, when inflated, reduce their eardrum's sensitivity to environmental noise in a specific frequency range, making it easier to zero in on the ...

Brain cells called astrocytes derived from the induced pluripotent stem cells of patients with bipolar disorder offer suboptimal support for neuronal activity. In a paper appearing March 4th in the journal Stem Cell Reports, researchers show that this malfunction can be traced to an inflammation-promoting molecule called interleukin-6 (IL-6), which is secreted by astrocytes. The results highlight the potential role of astrocyte-mediated inflammatory signaling in the psychiatric disease, although further investigation is needed.

"Our findings suggest that IL-6 may contribute to defects associated with bipolar disorder, opening new avenues for clinical intervention," says co-senior study author Fred Gage ...

New collaborative research from Northwestern University and Lund University may have people heading to their backyard instead of the store at the outset of this year's mosquito season.

Often used as an additive for cat toys and treats due to its euphoric and hallucinogenic effects on cats, catnip has also long been known for its powerful repellent action on insects, mosquitoes in particular. Recent research shows catnip compounds to be at least as effective as synthetic insect repellents such as DEET.

But until now, the mechanism that triggered insects' aversion to this common member of the mint family was unknown. In a paper ...

Existing gene drive technologies could be combined to help control the invasive grey squirrel population in the UK with little risk to other populations, according to a modelling study published in Scientific Reports.

Gene drives introduce genes into a population that have been changed to induce infertility in females, allowing for the control of population size. However, they face technical challenges, such as controlling the spread of altered genes as gene drive individuals mate with wild individuals, and the development of genetic resistance, which may render the gene drive ineffective.

To address these challenges, Nicky Faber and colleagues used computer modelling to investigate the effectiveness of a combination of three gene ...

Using theoretical models of bacterial metabolism and reproduction, scientists can predict the type of resistance that bacteria will develop when they are exposed to antibiotics. This has now been shown by an Uppsala University research team, in collaboration with colleagues in Cologne, Germany. The study is published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

In medical and pharmaceutical research, there is keen interest in finding the answer to how fast, and through which mechanisms, bacteria develop antibiotic resistance. Another goal is to understand how this resistance, in turn, affects bacterial growth and pathogenicity.

"This kind of knowledge would enable better tracking and slowing ...

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) are suitable for discovering the genes that underly complex and also rare genetic diseases. Scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), together with international partners, have studied genotype-phenotype relationships in iPSCs using data from approximately one thousand donors.

Tens of thousands of tiny genetic variations (SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms) have been identified in the human genome that are associated with specific diseases. Many of these genetic variants are ...

A team of scientists from the University of Cologne (Germany) and the University of Uppsala (Sweden) has created a model that can describe and predict the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Resistance to antibiotics evolves through a variety of mechanisms. A central and still unresolved question is how resistance evolution affects cell growth at different drug concentrations. The new model predicts growth rates and resistance levels of common resistant bacterial mutants at different drug doses. These predictions are confirmed by empirical growth inhibition curves and genomic data from Escherichia coli populations. ...

Over evolutionary time scales, a single gene may acquire different roles in diverging species. However, revealing the multiple hidden roles of a gene was not possible before genome editing came along. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor and HHMI Investigator Zach Lippman and CSHL postdoctoral fellow Anat Hendelman collaborated with Idan Efroni, HHMI International Investigator at Hebrew University Faculty of Agriculture in Israel, to uncover this mystery. They dissected the activity of a developmental gene, WOX9, in different plants and at different moments in development. Using genome editing, they found that without changing the protein produced by the gene, they ...

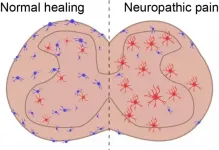

CHAPEL HILL, NC - One of the hallmarks of chronic pain is inflammation, and scientists at the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that anti-inflammatory cells called MRC1+ macrophages are dysfunctional in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Returning these cells to their normal state could offer a route to treating debilitating pain caused by nerve damage or a malfunctioning nervous system.

The researchers, who published their work in Neuron, found that stimulating the expression of an anti-inflammatory protein called CD163 reduced signs of neuroinflammation in the spinal cord of mice with neuropathic pain.

"Macrophages are a type of immune cell that are found in the blood and in tissues ...

What The Study Did: In this study of return-to-play cardiac testing performed on 789 professional athletes with COVID-19 infection, imaging evidence of inflammatory heart disease that resulted in restriction from play was identified in five athletes (0.6%). No adverse cardiac events occurred in the athletes who underwent cardiac screening and resumed professional sports participation.

Authors: David J. Engel, M.D., of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of ...