(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

That's the take-home of a new study that, for the first time, measures precisely how much water humans lose and replace each day compared with our closest living animal relatives.

Our bodies are constantly losing water: when we sweat, go to the bathroom, even when we breathe. That water needs to be replenished to keep blood volume and other body fluids within normal ranges.

And yet, research published March 5 in the journal Current Biology shows that the human body uses 30% to 50% less water per day than our closest animal cousins. In other words, among primates, humans evolved to be the low-flow model.

An ancient shift in our body's ability to conserve water may have enabled our hunter-gatherer ancestors to venture farther from streams and watering holes in search of food, said lead author Herman Pontzer, associate professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University.

"Even just being able to go a little bit longer without water would have been a big advantage as early humans started making a living in dry, savannah landscapes," Pontzer said.

The study compared the water turnover of 309 people with a range of lifestyles, from farmers and hunter-gatherers to office workers, with that of 72 apes living in zoos and sanctuaries.

To maintain fluid balance within a healthy range, the body of a human or any other animal is a bit like a bathtub: "water coming in has to equal water coming out," Pontzer said.

Lose water by sweating, for example, and the body's thirst signals kick in, telling us to drink. Chug more water than your body needs, and the kidneys get rid of the extra fluid.

For each individual in the study, the researchers calculated water intake via food and drink on the one hand, and water lost via sweat, urine and the GI tract, on the other hand.

When they added up all the inputs and outputs, they found that the average person processes some three liters, or 12 cups, of water each day. A chimpanzee or gorilla living in a zoo goes through twice that much.

Pontzer says the researchers were surprised by the results because, among primates, humans have an amazing ability to sweat. Per square inch of skin, "humans have 10 times as many sweat glands as chimpanzees do," Pontzer said. That makes it possible for a person to sweat more than half a gallon during an hour-long workout -- equivalent to two Big Gulps from a 7-Eleven.

Add to that the fact that the great apes -- chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans -- live lazy lives. "Most apes spend 10 to 12 hours a day resting or feeding, and then they sleep for 10 hours. They really only move a couple hours a day," Pontzer said.

But the researchers controlled for differences in climate, body size, and factors like activity level and calories burned per day. So they concluded the water-savings for humans were real, and not just a function of where individuals lived or how physically active they were.

The findings suggest that something changed over the course of human evolution that reduced the amount of water our body uses each day to stay healthy.

Then as now, we could likely still only survive a few days without drinking, Pontzer said. "You probably don't break that ecological leash, but at least you get a longer one if you can go longer without water."

The next step, Pontzer says, is to pinpoint how this physiological change happened.

One hypothesis, suggested by the data, is that our body's thirst response was re-tuned so that, overall, we crave less water per calorie compared with our ape relatives. Even as babies, long before our first solid food, the water-to-calories ratio of human breast milk is 25% less than the milks of other great apes.

Another possibility lies in front of our face: Fossil evidence suggests that, about 1.6 million years ago, with the inception of Homo erectus, humans started developing a more prominent nose. Our cousins gorillas and chimpanzees have much flatter noses.

Our nasal passages help conserve water by cooling and condensing the water vapor from exhaled air, turning it back into liquid on the inside of our nose where it can be reabsorbed.

Having a nose that sticks out more may have helped early humans retain more moisture with each breath.

"There's still a mystery to solve, but clearly humans are saving water," Pontzer said. "Figuring out exactly how we do that is where we go next, and that's going to be really fun."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (BCS-0643122, BCS-1317170, BCS-1440867, BCS-1440841, BCS-1440671), the United States Agency for International Development (APS-497-11-000001), the National Institutes of Health (R01DK080763), the John Templeton Foundation, L.S.B. Leakey Foundation, Wenner-Gren Foundation (Gr. 8670), the University of Arizona, Duke University, and Hunter College.

CITATION: "Evolution of Water Conservation in Humans," Herman Pontzer, Mary H. Brown, Brian M. Wood, David A. Raichlen, Audax. Z.P. Mabulla, Jacob A. Harris, Holly Dunsworth, Brian Hare, Kara Walker, Amy Luke, Lara R. Dugas, Dale Schoeller, Jacob Plange-Rhule, Pascal Bovet, Terrence E. Forrester, Melissa Emery Thompson, Robert W. Shumaker, Jessica M. Rothman, Erin Vogel, Fransiska Sulistyo, Shauhin Alavi, Didik Prasetyo, Samuel S. Urlacher, and Stephen R. Ross. Current Biology, March 5, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.045

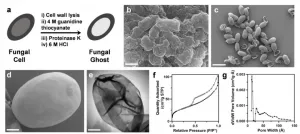

The idea of creating selectively porous materials has captured the attention of chemists for decades. Now, new research from Northwestern University shows that fungi may have been doing exactly this for millions of years.

When Nathan Gianneschi's lab set out to synthesize melanin that would mimic that which was formed by certain fungi known to inhabit unusual, hostile environments including spaceships, dishwashers and even Chernobyl, they did not initially expect the materials would prove highly porous-- a property that enables the material to store and capture molecules.

Melanin has been found across living organisms, on our skin and the backs of ...

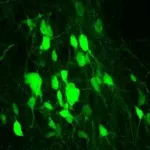

Using genetic engineering, researchers at UT Southwestern and Indiana University have reprogrammed scar-forming cells in mouse spinal cords to create new nerve cells, spurring recovery after spinal cord injury. The findings, published online today in Cell Stem Cell, could offer hope for the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who suffer a spinal cord injury each year.

Cells in some body tissues proliferate after injury, replacing dead or damaged cells as part of healing. However, explains study leader END ...

What The Study Did: The objectives of this study were to examine the characteristics and outcomes among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 at U.S. medical centers and analyze changes in mortality over the initial six months of the pandemic.

Authors: Ninh T. Nguyen, M.D., of the University of California, Irvine Medical Center, in Orange, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0417)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

What The Study Did: Survey data were used to estimate changes in racial/ethnic disparities in rates of autism spectrum disorder among U.S. children and adolescents from 2014 through 2019.

Authors: Z. Kevin Lu, Ph.D., of the University of South Carolina in Columbia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0771)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined the association of increased anti-immigrant rhetoric during the 2016 presidential campaign with changes in the use of health care services among undocumented patients.

Authors: Joseph Nwadiuko, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.H.P., of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0763)

Editor's Note: Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article ...

What The Study Did: In this study, many children and adolescents hospitalized for COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children had neurologic involvement, mostly transient symptoms. A range of life-threatening and fatal neurologic conditions associated with COVID-19 infrequently occurred. Effects on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes are unknown.

Authors: Adrienne G. Randolph, M.D., of Boston Children's Hospital, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0504)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

DNA sequencing of bacteria found in pigs and humans in rural eastern North Carolina, an area with concentrated industrial-scale pig-farming, suggests that multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains are spreading between pigs, farmworkers, their families and community residents, and represents an emerging public health threat, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

S. aureus is commonly found in soil and water, as well as on the skin and in the upper respiratory tract in pigs, other animals, and people. It can cause medical problems from minor skin infections to serious surgical wound infections, pneumonia, and the often-lethal blood-infection condition known as sepsis. The findings provide evidence that multidrug-resistant ...

Researchers from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, have collaborated on two studies examining the socioeconomic factors involved in the spread of COVID-19.

Professor Alex Bentley and postdoctoral fellow Damian Ruck, both from the Department of Anthropology, joined Josh Borycz, a librarian at Vanderbilt University, to conduct the studies.

"One of our studies considers the global scale of nations and the other uses the national scale for US counties to analyze results during 2020," explained Bentley.

The studies show that the numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths are significantly affected ...

Two thirds of children use more than one screen at the same time after school, in the evenings and at weekends as part of increasingly sedentary lifestyles, according to new research at the University of Leicester.

An NIHR study of more than 800 adolescent girls between the ages of 11 and 14 identified worrying trends between screen use and lower physical activity - including higher BMI - as well as less sleep.

The use of concurrent screens (termed 'screen stacking') grew over the course of the week - with 59% of adolescents using two or more screens after school, 65% in the evenings, and 68% at weekends.

Some teens reporting using as many as four screens at one time.

But further analysis showed the use of any screen was still detrimental to the indicators ...

A new study from the University of Iowa sought to begin development of a possible approach to reduce the risk that college-aged men engage in sexually aggressive acts or risky sexual behavior.

The study authors, led by Teresa Treat, professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Iowa, developed a 12-point list of sexual assault prevention strategies. The list was created by the researchers based on previous research into risk factors that are associated with sexually aggressive acts--such as heavy alcohol consumption, difficulties reading women's cues, and not seeking consent for sexual activity.

The authors found that 71% of the college-aged men surveyed used the sexual assault prevention strategies on a regular basis over the past year. Yet 15% of the ...