Study finds brain's 'wiring insulation' as major factor of age-related brain deterioration

2021-03-09

(Press-News.org) A new study led by the University of Portsmouth has identified that one of the major factors of age-related brain deterioration is the loss of a substance called myelin.

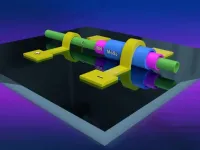

Myelin acts like the protective and insulating plastic casing around the electrical wires of the brain - called axons. Myelin is essential for superfast communication between nerve cells that lie behind the supercomputer power of the human brain.

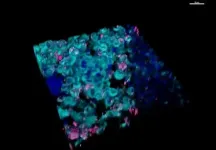

The loss of myelin results in cognitive decline and is central to several neurodegenerative diseases, such as Multiple Sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. This new study found that the cells that drive myelin repair become less efficient as we age and identified a key gene that is most affected by ageing, which reduces the cells ability to replace lost myelin.

The study, published this week in the journal Ageing Cell, is part of an international collaboration led by Professor Arthur Butt at the University of Portsmouth with Dr Kasum Azim at the University of Dusseldorf in Germany, together with Italian research groups of Professor Maria Pia Abbracchio in Milan and Dr Andrea Rivera in Padua.

Professor Butt said: "Everyone is familiar with the brain's grey matter, but very few know about the white matter, which comprises of the insulated electrical wires that connect all the different parts of our brains.

"A key feature of the ageing brain is the progressive loss of white matter and myelin, but the reasons behind these processes are largely unknown. The brain cells that produce myelin - called oligodendrocytes - need to be replaced throughout life by stem cells called oligodendrocyte precursors. If this fails, then there is a loss of myelin and white matter, resulting in devastating effects on brain function and cognitive decline. An exciting new finding of our study is that we have uncovered one of the reasons that this process is slowed down in the aging brain."

Dr Rivera, lead author of the study while he was in University of Portsmouth and who is now a Fellow at the University of Padua, explained: "By comparing the genome of a young mouse brain to that of a senile mouse, we identified which processes are affected by ageing. These very sophisticated analysis allowed us to unravel the reasons why the replenishment of oligodendrocytes and the myelin they produce is reduced in the aging brain.

"We identified GPR17, the gene associated to these specific precursors, as the most affected gene in the ageing brain and that the loss of GPR17 is associated to a reduced ability of these precursors to actively work to replace the lost myelin."

The work is still very much ongoing and has paved the way for new studies on how to induce the 'rejuvenation' of oligodendrocyte precursor cells to efficiently replenish lost white matter.

Dr Azim of the University of Dusseldorf said: "This approach is promising for targeting myelin loss in the aging brain and demyelination diseases, including Multiple Sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease and neuropsychiatric disorders. Indeed, we have only touched the tip of the iceberg and future investigation from our research groups aim to bring our findings into human translational settings."

Dr Rivera performed the key experiments published in this study while at the University of Portsmouth and he has been awarded the prestigious MSCA Seal of Excellence @UniPD Fellowship to translate these findings and investigate this further in the human brain, in collaboration with Professors Raffele De Caro, Andrea Porzionato and Veronica Macchi at the Institute of Human Anatomy of the University of Padua.

The study was funded by grants from the BBSRC and MRC to Professor Butt, together with the UK and Italian MS Societies (to Professors Butt and Abbracchio, respectively), and the Swiss National Funds Fellowship and German Research Council (Dr Azim). Dr Andrea Rivera was supported by an Anatomical Society PhD Studentship (with Professor Butt), and the MSCA Seal of Excellence @UniPD (Dr Rivera).

Dr Emma Gray, Assistant Director of Research at the MS Society, said: "MS can be relentless and painful, and there are sadly still no treatments to stop disability progression. We can see a future where no one has to worry about MS getting worse but, for that to happen, we need to find ways to repair damaged myelin. This research sheds light on why cells that drive myelin repair become less efficient as we age, and we're really proud to have helped fund it. By improving our understanding of ageing brain stem cells, it gives us a new target to help slow the progression of MS, and could have important implications for future treatment."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-09

The recent synthesis of one-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures, a type of heterostructure made by layering two-dimensional materials that are one atom thick, may lead to new, miniaturized electronics that are currently not possible, according to a team of Penn State and University of Tokyo researchers.

Engineers commonly produce heterostructures to achieve new device properties that are not available in a single material. A van der Waals heterostructure is one made of 2D materials that are stacked directly on top of each other like Lego-blocks or a sandwich. The van der Waals force, which is an attractive force between uncharged molecules or atoms, holds the materials together.

According to Slava V. Rotkin, Penn State Frontier ...

2021-03-09

Intervention research focusing on patients with multiple, simultaneous chronic illnesses is a priority for health organizations such as the National Institutes of Health and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. This is important as physicians seek to better understand how one disease may influence the course of another coexisting one, and how to best care for patients who are battling multiple health issues. Researchers conducted a controlled trial in patients 18 to 80 years with three or more chronic conditions. They collected quantitative data and conducted in-depth interviews with patients, family members and health care providers, then measured the ...

2021-03-09

Cooperation is generally a good thing -- working together to reach a goal.

But in the case of cancer, it can be detrimental. University of Cincinnati researchers have discovered that cooperation between two key genes drive cancer growth, spread and treatment resistance in one particularly aggressive type of breast cancer.

The good news is, though, with this knowledge, they can continue to aim their targeted treatments at these genes, singularly and together, to stop breast cancer in its tracks.

This study is published in the March 9 online edition of the journal Cell Reports.

"According to the American Cancer Society's estimate, over 280,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in women in 2021," explains Xiaoting Zhang, PhD, professor and Thomas Boat Endowed Chair ...

2021-03-09

Some of Princeton's leading cancer researchers were startled to discover that what they thought was a straightforward investigation into how cancer spreads through the body -- metastasis -- turned up evidence of liquid-liquid phase separations: the new field of biology research that investigates how liquid blobs of living materials merge into each other, similar to the movements seen in a lava lamp or in liquid mercury.

"We believe this is the first time that phase separation has been implicated in cancer metastasis," said Yibin Kang, the Warner-Lambert/Parke-Davis Professor of Molecular Biology. He is the ...

2021-03-09

Broad political, economic, and social factors influence disciplinary punishment. In particular, over the last half century, such considerations have shaped jurisdictions' use of the death penalty, which has declined considerably since the 1990s. A new study examined the factors associated with use of the death penalty at the county level to provide a fuller picture of what issues influence court outcomes. The study concludes that partisan politics, religious fundamentalism, and economic threat influenced local decisions about the death penalty. The study also found that the size of the African American population, which ...

2021-03-09

CHAPEL HILL, NC -- In a viewpoint perspective published in JAMA on March 9, 2021, a University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center researcher and two other experts endorsed the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services' (CMS) requirement for a patient and their doctor to engage in a shared discussion of benefits and harms before proceeding with a low-dose spiral computed tomography (LDCT) scan as a method for preventing lung cancer death. An accompanying evidence report detailed the benefits and harms from screening, suggesting that shared decision-making between a patient ...

2021-03-09

URBANA, Ill. - If you haven't been the parent or caregiver of an infant in recent years, you'd be forgiven for missing the human milk oligosaccharide trend in infant formulas. These complex carbohydrate supplements mimic human breast milk and act like prebiotics, boosting beneficial microbes in babies' guts.

Milk oligosaccharides aren't just for humans, though; all mammals make them. And new University of Illinois research suggests milk oligosaccharides may be beneficial for cats and dogs when added to pet diets.

But before testing the compounds, scientists had to find them.

"When we first looked into this, there had only been one study on milk oligosaccharides in dogs, and none in domestic cats. The closest were really small studies on a single lion and a single ...

2021-03-09

In a new study in PNAS, an international team of researchers including scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology has shown that Arabidopsis thaliana plants produce beta-cyclocitral when attacked by herbivores and that this volatile signal inhibits the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway. The MEP pathway is instrumental in plant growth processes, such as the production of pigments for photosynthesis. In addition to down-regulating the MEP pathway, beta-cyclocitral also increases plant defenses against herbivores. Since the MEP pathway is only found in plants and microorganisms, but not animals, knowledge of a signal molecule like beta-cyclocitral opens up new possibilities for the development ...

2021-03-09

Brazilian researchers who study a native venomous fish have confirmed a route to drug development for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis and asthma.

The venomous toadfish Thalassophryne nattereri contains a peptide (TnP) with anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic potential. Confirmation of this potential has now come via the zebrafish Danio rerio, a popular aquarium species native to South Asia that shares 70% of its genome with humans and is widely used as a model for in vivo trials in drug development.

The researchers tested TnP in D. rerio to measure its toxicity. In a little over a year, their research showed that the peptide is safe. It did not cause cardiac dysfunction or neurological problems in the toxicity tests ...

2021-03-09

Health care systems could save lives and minimize losses by optimizing resource allocation and implementing mitigation strategies, according to two new studies. Colorado State University researchers explored how our health care systems might perform under multiple disasters and multiple waves of COVID-19, and how we can keep them functioning when we need them most.

In the first study, published in Nature Communications, Civil and Environmental Engineering Ph.D. student Emad Hassan and Associate Professor Hussam Mahmoud investigated the compound effects of pandemics and natural disasters on health care systems. They combined wildfire ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study finds brain's 'wiring insulation' as major factor of age-related brain deterioration