Wing tags severely impair flight in African Cape Vultures

Study urges the use of leg bands for marking individuals instead of wing tags

2021-03-11

(Press-News.org) Conservationists who apply wing tags for identifying Cape Vultures--a species of African vulture that is vulnerable to extinction--are putting the birds' lives further at risk, a new movement ecology study has shown. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany and VulPro NPC in South Africa have demonstrated that Cape Vultures fitted with tags on their wings travelled shorter distances and flew slower than those fitted with bands around their legs. The research emphasises the importance of investigating the effects that tagging methods can have on the behaviour and conservation of species, prompting a shift towards the less invasive method of leg bands in the future study of Cape Vultures.

For over a decade, many conservationists and NGOs have been marking vultures by placing a tag on the wing area known as the patagium. Patagial tags have the advantage that they are large and conspicuous enough for individuals to be identified from far away. Leg bands are smaller in size, fitted around the tarsus of the vultures leg and thus, harder to notice and record the unique number.

"After receiving many grounded and injured vultures from incorrect placement of wing tags, we felt there was an immediate need to find out exactly what these tags were doing to the flight of birds and whether this technique was, in fact, hindering the species rather than protecting them," says senior author Kerri Wolter, CEO of VulPro NPC, a vulture conservation organisation in South Africa.

The study was motivated by recent VulPro NPC research, which highlighted how an incorrect patagial tag could cause injuries and result in the grounding of vultures. To find out how patagial tags affected the birds' flights, researchers from the Max Planck Institute used GPS devices to track 27 Cape Vultures (Gyps coprotheres) marked with either patagial tags or leg bands.

The GPS devices, which were mounted to the birds' backs, recorded the birds' positions as often as every minute for 24 hours a day. These recordings allowed researchers to investigate the birds' flight performance, including occurrence of flight, proportion of time spent flying in a day, daily distance travelled and ground speed.

Individuals equipped with patagial tags covered a much smaller area in comparison to the leg band group. They were less likely to take flight and, when doing so, flew at lower ground speed compared to individuals wearing leg bands.

"Although we did not measure the effects of patagial tags on body condition or survival, our results strongly suggest that patagial tags have severe adverse effects on vultures' flight performance," says first author Teja Curk, a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior.

Vultures are scavengers. By feeding on dead animals, they play an important role in the ecosystem due to the services they provide, such as preventing the spread of infectious diseases, recycling organic material into nutrients and stabilising food webs.

"Therefore, restricted flight potential and a reduction in the area covered by these birds, caused by improper tag attachment, can have far-reaching consequences at the ecosystem level," says co-author Kamran Safi, a group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior.

INFORMATION:

Original publication

Teja Curk, Martina Scacco, Kamran Safi, Martin Wikelski, Wolfgang Fiedler, Ryno Kemp and Kerri Wolter

Wing tags severely impair movement in African Cape Vultures

Animal Biotelemetry 9(11)

09 March 2021

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-11

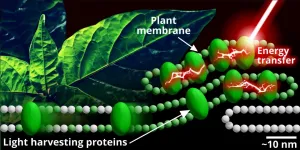

New scientific techniques are revealing the intricate role that proteins play in photosynthesis.

Despite being discovered almost 300 years ago, photosynthesis still holds many unanswered questions for science, particularly the way that proteins organise themselves to convert sunlight into chemical energy and at the same time, protect plants from too much sunlight.

Now a collaboration between researchers at the University of Leeds and Kobe University in Japan is developing a novel approach to the investigation of photosynthesis.

Using hybrid membranes that mimic natural plant membranes and advanced microscopes, they are opening photosynthesis to nanoscale investigation - the study of life at less than one billionth ...

2021-03-11

In snowy plovers, females have overcome traditional family stereotypes. They often abandon the family to begin a clutch with a new partner whereas the males continue to care for their young until they are independent. An international team led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Seewiesen, Germany, has now investigated the decision-making process that determines the duration of parental care by females. They found that offspring desertion often occurs either under poor environmental conditions, when chicks die despite being cared for by both parents, ...

2021-03-11

To highlight tumours in the body for cancer diagnosis, doctors can use tiny optical probes (nanoprobes) that light up when they attach to tumours. These nanoprobes allow doctors to detect the location, shape and size of cancers in the body.

Most nanoprobes are fluorescent; they absorb light of a specific colour, like blue and then emit back light of a different colour, like green. However, as tissues of the human body can emit light as well, distinguishing the nanoprobe light from the background light can be tough and could lead to the wrong interpretation.

Now, researchers at Imperial College London have developed new nanoprobes, named bioharmonophores and patented at Imperial, ...

2021-03-11

About 1.8 million envenoming snakebites occur around the world annually, killing about 94,000 people. In tropical areas, especially in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, snakebites are considered a major cause of death, especially among farmers who encounter snakes in their fields. In response, the World Health Organization has launched a strategic plan to reduce snakebites by 50% by 2030. An important basis for attaining this goal is expanding relevant scientific research.

An international research group, including researchers from Tel Aviv University, has recently created an innovative simulation model for predicting snakebites, based on an improved ...

2021-03-11

A rare disease first identified in 2020 is much more common than first thought, say researchers at the University of Leeds investigating its origins.

VEXAS syndrome is a serious inflammatory condition which develops in men over 50, causing them to become very sick and fatigued, and can be fatal. It was originally thought to be rare, but a new study has identified genetic mutations which indicate that the disease is actually much more common.

The researchers developed a genetic test to identify patients who may have the disease, and now want to screen more people showing symptoms to understand exactly how common it is.

VEXAS syndrome causes unexplained fevers, painful skin rashes and affects the bone ...

2021-03-11

The conditions on Earth are ideal for life. Most places on our planet are neither too hot nor too cold and offer liquid water. These and other requirements for life, however, delicately depend on the right composition of the atmosphere. Too little or too much of certain gases - like carbon dioxide - and Earth could become a ball of ice or turn into a pressure cooker. When scientists look for potentially habitable planets, a key component is therefore their atmosphere.

Sometimes, that atmosphere is primitive and largely consists of the gases that were around when the planet formed - as is the case for Jupiter and Saturn. On terrestrial planets like Mars, Venus or Earth, however, such primitive atmospheres are lost. Instead, their remaining atmospheres are strongly influenced ...

2021-03-11

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Electric stimulation may be able to help blood vessels carry white blood cells and oxygen to wounds, speeding healing, a new study suggests.

The study, published in the Royal Society of Chemistry journal Lab on a Chip, found that steady electrical stimulation generates increased permeability across blood vessels, providing new insight into the ways new blood vessels might grow.

The electrical stimulation provided a constant voltage with an accompanying electric current in the presence of fluid flow. The findings indicate that stimulation increases ...

2021-03-11

Grass pollen is a major outdoor allergen, responsible for widespread and costly respiratory conditions including allergic asthma and hay fever (rhinitis). Now, researchers re-porting in the journal Current Biology on March 11 suggest that environmental DNA could help to better understand which grasses are the worst offenders.

"These findings represent a first step towards changing and improving our understanding of the complex relationships between pollen and population health," said Benedict Wheeler of the University of Exeter, UK. "If confirmed and refined, this research could help to improve pollen forecasts and warnings in the future, supporting individual and community-level prevention strategies and management ...

2021-03-11

Hormones produced by the thyroid gland are essential regulators of organ function. The absence of these hormones either through thyroid dysfunction due to, for example, irradiation, thyroid cancer or autoimmune disease or thyroidectomy leads to symptoms like fatigue, feeling cold, constipation, and weight gain. The condition called hypothyroidism is estimated to affect up to 11% of the global population. Although hypothyroidism can be treated by hormone replacement therapy, some patients have persistent symptoms and/or experience side effects. To investigate potential alternative treatment strategies for these patients, researchers have now for the first time succeeded in generating thyroid mini-organs in the lab. In a END ...

2021-03-11

People often choose the standard option. Choosing to be an organ donor, printing on both sides of the page - such decisions are influenced by which is the standard setting, or default. In fact, economists and sociologists call this the default effect. Researchers at ETH Zurich and the University of Warwick in the UK have now managed to clearly demonstrate this effect. Private households, but also self-employed people and SMEs, are more likely to procure sustainably produced electricity if that is their provider's default offer.

The scientists conclude this from an analysis of data from two Swiss electricity suppliers - one large and one medium-sized. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Wing tags severely impair flight in African Cape Vultures

Study urges the use of leg bands for marking individuals instead of wing tags