Starting small to answer the big questions about photosynthesis

2021-03-11

(Press-News.org) New scientific techniques are revealing the intricate role that proteins play in photosynthesis.

Despite being discovered almost 300 years ago, photosynthesis still holds many unanswered questions for science, particularly the way that proteins organise themselves to convert sunlight into chemical energy and at the same time, protect plants from too much sunlight.

Now a collaboration between researchers at the University of Leeds and Kobe University in Japan is developing a novel approach to the investigation of photosynthesis.

Using hybrid membranes that mimic natural plant membranes and advanced microscopes, they are opening photosynthesis to nanoscale investigation - the study of life at less than one billionth of a metre - to reveal the behaviour of individual protein molecules.

Dr Peter Adams, Associate Professor in the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Leeds, who supervised the research, said: "For many decades scientists have been developing an understanding of photosynthesis in terms of the biology of whole plants. This research is tackling it at the molecular level and the way proteins interact.

"A greater understanding of photosynthesis will benefit humankind. It will help scientists identify new ways to protect and boost crop yields, as well as inspire technologists to develop new solar-powered materials and components."

The findings are published in the academic journal Small.

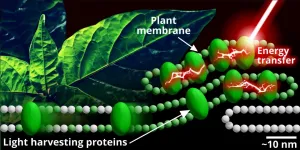

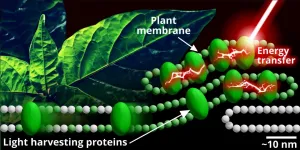

Photosynthesis happens when photons or packets of light energy cause pigments inside light-harvesting proteins to become excited. The way that these proteins arrange themselves determines how the energy is transferred to other molecules.

It is a complex system that plays out across many different pigments, proteins, and layers of light-harvesting membranes within the plant. Together, it regulates energy absorption, transfer, and the conversion of this energy into other useful forms.

To understand this intricate process, scientists have been using a technique called atomic force microscopy, which is a device capable of revealing components of a membrane that are a few nanometres in size.

The difficulty is that natural plant membranes are very fragile and can be damaged by atomic force microscopy.

But last year, the researchers at Kobe University announced that they had developed a hybrid membrane made up of natural plant material and synthetic lipids that would act as a substitute for a natural plant membrane - and crucially, is more stable when placed in an atomic force microscope.

The team at the University of Leeds used the hybrid membrane and subjected it to atomic force microscopy and another advanced visualisation technique called fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy, or FLIM.

PhD researcher Sophie Meredith, also from the School of Physics at the University of Leeds, is the lead author in the paper. She said: "The combination of FLIM and atomic force microscopy allowed us to observe the elements of photosynthesis. It gave us an insight into the dynamic behaviors and interactions that take place.

"What is important is that we can control some of the parameters in the hybrid membrane, so we can isolate and control factors, and that helps with experimental investigation.

"In essence, we now have a 'testbed' and a suite of advanced imaging tools that will reveal the sub-molecular working of photosynthesis."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the Royal Society, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The paper - Model Lipid Membranes Assembled from Natural Plant Thylakoids into 2D Microarray Patterns as a Platform to Assess the Organization and Photophysics of Light-Harvesting Proteins - is available to download at https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202006608

For further information, please contact David Lewis in the press office at the University of Leeds: d.lewis@leeds.ac.uk or on +44 (0)7710 013287

The is an image that goes with the story. The caption is: Light is absorbed by light-harvesting proteins in the plant membrane. The energy excites the proteins and the way they arrange themselves determines the way energy is transferred through the plant.

Please credit the image: Sophie Meredith, University of Leeds.

University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 37,000 students from more than 150 different countries, and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. The University plays a significant role in the Turing, Rosalind Franklin and Royce Institutes.

We are a top ten university for research and impact power in the UK, according to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, and are in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings 2019.

The University was awarded a Gold rating by the Government's Teaching Excellence Framework in 2017, recognising its 'consistently outstanding' teaching and learning provision. Twenty-six of our academics have been awarded National Teaching Fellowships - more than any other institution in England, Northern Ireland and Wales - reflecting the excellence of our teaching. http://www.leeds.ac.uk

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-11

In snowy plovers, females have overcome traditional family stereotypes. They often abandon the family to begin a clutch with a new partner whereas the males continue to care for their young until they are independent. An international team led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Seewiesen, Germany, has now investigated the decision-making process that determines the duration of parental care by females. They found that offspring desertion often occurs either under poor environmental conditions, when chicks die despite being cared for by both parents, ...

2021-03-11

To highlight tumours in the body for cancer diagnosis, doctors can use tiny optical probes (nanoprobes) that light up when they attach to tumours. These nanoprobes allow doctors to detect the location, shape and size of cancers in the body.

Most nanoprobes are fluorescent; they absorb light of a specific colour, like blue and then emit back light of a different colour, like green. However, as tissues of the human body can emit light as well, distinguishing the nanoprobe light from the background light can be tough and could lead to the wrong interpretation.

Now, researchers at Imperial College London have developed new nanoprobes, named bioharmonophores and patented at Imperial, ...

2021-03-11

About 1.8 million envenoming snakebites occur around the world annually, killing about 94,000 people. In tropical areas, especially in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, snakebites are considered a major cause of death, especially among farmers who encounter snakes in their fields. In response, the World Health Organization has launched a strategic plan to reduce snakebites by 50% by 2030. An important basis for attaining this goal is expanding relevant scientific research.

An international research group, including researchers from Tel Aviv University, has recently created an innovative simulation model for predicting snakebites, based on an improved ...

2021-03-11

A rare disease first identified in 2020 is much more common than first thought, say researchers at the University of Leeds investigating its origins.

VEXAS syndrome is a serious inflammatory condition which develops in men over 50, causing them to become very sick and fatigued, and can be fatal. It was originally thought to be rare, but a new study has identified genetic mutations which indicate that the disease is actually much more common.

The researchers developed a genetic test to identify patients who may have the disease, and now want to screen more people showing symptoms to understand exactly how common it is.

VEXAS syndrome causes unexplained fevers, painful skin rashes and affects the bone ...

2021-03-11

The conditions on Earth are ideal for life. Most places on our planet are neither too hot nor too cold and offer liquid water. These and other requirements for life, however, delicately depend on the right composition of the atmosphere. Too little or too much of certain gases - like carbon dioxide - and Earth could become a ball of ice or turn into a pressure cooker. When scientists look for potentially habitable planets, a key component is therefore their atmosphere.

Sometimes, that atmosphere is primitive and largely consists of the gases that were around when the planet formed - as is the case for Jupiter and Saturn. On terrestrial planets like Mars, Venus or Earth, however, such primitive atmospheres are lost. Instead, their remaining atmospheres are strongly influenced ...

2021-03-11

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Electric stimulation may be able to help blood vessels carry white blood cells and oxygen to wounds, speeding healing, a new study suggests.

The study, published in the Royal Society of Chemistry journal Lab on a Chip, found that steady electrical stimulation generates increased permeability across blood vessels, providing new insight into the ways new blood vessels might grow.

The electrical stimulation provided a constant voltage with an accompanying electric current in the presence of fluid flow. The findings indicate that stimulation increases ...

2021-03-11

Grass pollen is a major outdoor allergen, responsible for widespread and costly respiratory conditions including allergic asthma and hay fever (rhinitis). Now, researchers re-porting in the journal Current Biology on March 11 suggest that environmental DNA could help to better understand which grasses are the worst offenders.

"These findings represent a first step towards changing and improving our understanding of the complex relationships between pollen and population health," said Benedict Wheeler of the University of Exeter, UK. "If confirmed and refined, this research could help to improve pollen forecasts and warnings in the future, supporting individual and community-level prevention strategies and management ...

2021-03-11

Hormones produced by the thyroid gland are essential regulators of organ function. The absence of these hormones either through thyroid dysfunction due to, for example, irradiation, thyroid cancer or autoimmune disease or thyroidectomy leads to symptoms like fatigue, feeling cold, constipation, and weight gain. The condition called hypothyroidism is estimated to affect up to 11% of the global population. Although hypothyroidism can be treated by hormone replacement therapy, some patients have persistent symptoms and/or experience side effects. To investigate potential alternative treatment strategies for these patients, researchers have now for the first time succeeded in generating thyroid mini-organs in the lab. In a END ...

2021-03-11

People often choose the standard option. Choosing to be an organ donor, printing on both sides of the page - such decisions are influenced by which is the standard setting, or default. In fact, economists and sociologists call this the default effect. Researchers at ETH Zurich and the University of Warwick in the UK have now managed to clearly demonstrate this effect. Private households, but also self-employed people and SMEs, are more likely to procure sustainably produced electricity if that is their provider's default offer.

The scientists conclude this from an analysis of data from two Swiss electricity suppliers - one large and one medium-sized. ...

2021-03-11

Researchers studying the Swiss energy market have found that making green energy the default option for consumers leads to an enduring shift to renewables and thus has the potential to cut CO2 emissions by millions of tonnes.

The study, published today in Nature Human Behaviour, investigated the effect of changes in the Swiss energy market that presented energy from renewable sources as the standard option for consumers - the 'green default.'

Both business and private customers largely accepted the default option, even though it was slightly more expensive, and the switch to green sources proved a lasting one.

Professor Ulf Liebe (University of Warwick), Doctor Jennifer Gewinner and Professor em. Andreas Diekmann (both ETH Zurich) analysed data from two Swiss ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Starting small to answer the big questions about photosynthesis