Skoltech team shows how Turing-like patterns fool neural networks

2021-03-11

(Press-News.org) Skoltech researchers were able to show that patterns that can cause neural networks to make mistakes in recognizing images are, in effect, akin to Turing patterns found all over the natural world. In the future, this result can be used to design defenses for pattern recognition systems currently vulnerable to attacks. The paper, available as an arXiv preprint, was presented at the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-21).

Deep neural networks, smart and adept at image recognition and classification as they already are, can still be vulnerable to what's called adversarial perturbations: small but peculiar details in an image that cause errors in neural network output. Some of them are universal: that is, they interfere with the neural network when placed on any input.

These perturbations can represent a significant security risk: for instance, in 2018, one team published a preprint describing a way to trick self-driving vehicles into "seeing" benign ads and logos on them as road signs. The fact that most known defenses a network can have against such an attack can be easily circumvented exacerbates this problem.

Professor Ivan Oseledets, who leads the Skoltech Computational Intelligence Lab at the Center for Computational and Data-Intensive Science and Engineering (CDISE), and his colleagues further explored a theory that connects these universal adversarial perturbations (UAPs) and classical Turing patterns, first described by the outstanding English mathematician Alan Turing as the driving mechanism behind a lot of patterns in nature, such as stripes and spots on animals.

The research started serendipitously when Oseledets and Valentin Khrulkov presented a paper on generating UAPs at the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition in 2018. "A stranger came by and told us that this patterns look like Turing patterns. This similarity was a mystery for several years, until Skoltech master students Nurislam Tursynbek, Maria Sindeeva and PhD student Ilya Vilkoviskiy formed a team that was able to solve this puzzle. This is also a perfect example of internal collaboration at Skoltech, between the Center for Advanced Studies and Center for Data-Intensive Science and Engineering," Oseledets says.

The nature and roots of adversarial perturbations are still mysterious for researchers. "This intriguing property has a long history of cat-and-mouse games between attacks and defenses. One of the reasons why adversarial attacks are hard to defend against is lack of theory. Our work makes a step towards explaining the fascinating properties of UAPs by Turing patterns, which have solid theory behind them. This will help construct a theory of adversarial examples in the future," Oseledets notes.

There is prior research showing that natural Turing patterns - say, stripes on a fish - can fool a neural network, and the team was able to show this connection in a straightforward way and provide ways of generating new attacks. "The simplest setting to make models robust based on such patterns is to merely add them to images and train the network on perturbed images," the researcher adds.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-11

An enzyme called MARK2 has been identified as a key stress-response switch in cells in a study by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Overactivation of this type of stress response is a possible cause of injury to brain cells in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. The discovery will make MARK2 a focus of investigation for its possible role in these diseases, and may ultimately be a target for neurodegenerative disease treatments.

In addition to its potential relevance to neurodegenerative diseases, the finding is an advance in understanding basic cell biology.

The paper describing ...

2021-03-11

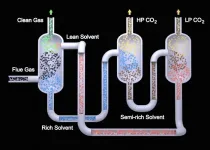

RICHLAND, Wash.--As part of a marathon research effort to lower the cost of carbon capture, chemists have now demonstrated a method to seize carbon dioxide (CO2) that reduces costs by 19 percent compared to current commercial technology. The new technology requires 17 percent less energy to accomplish the same task as its commercial counterparts, surpassing barriers that have kept other forms of carbon capture from widespread industrial use. And it can be easily applied in existing capture systems.

In a study published in the March 2021 edition of International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory--along with collaborators from ...

2021-03-11

MADISON, Wis. -- Mexican wolves in the American Southwest disappeared more quickly during periods of relaxed legal protections, almost certainly succumbing to poaching, according to new research published Wednesday.

Scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that Mexican wolves were 121% more likely to disappear -- despite high levels of monitoring through radio collars -- when legal rulings permitted easier lethal and non-lethal removal of the protected wolves between 1998 and 2016. The disappearances were not due to legal removal, the researchers say, but instead were likely caused by poachers hiding evidence of their activities.

The findings suggest that consistently strong protections for endangered predators lead ...

2021-03-11

Fossil sites sometimes resemble a living room table on which half a dozen different jigsaw puzzles have been dumped: It is often difficult to say which bone belongs to which animal. Together with colleagues from Switzerland, researchers from the University of Bonn have now presented a method that allows a more certain answer to this question. Their results are published in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

Fossilized dinosaur bones are relatively rare. But if any are found, it is often in large quantities. "Many sites contain the remains of dozens of animals," explains Prof. Dr. Martin Sander from the Institute ...

2021-03-11

For the first time ever, a Northwestern University-led research team has peered inside a human cell to view a multi-subunit machine responsible for regulating gene expression.

Called the Mediator-bound pre-initiation complex (Med-PIC), the structure is a key player in determining which genes are activated and which are suppressed. Mediator helps position the rest of the complex -- RNA polymerase II and the general transcription factors -- at the beginning of genes that the cell wants to transcribe.

The researchers visualized the complex in high resolution using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), ...

2021-03-11

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is already widely used in medicine for diagnostic purposes. Hyperpolarized MRI is a more recent development and its research and application potential has yet to be fully explored. Researchers at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and the Helmholtz Institute Mainz (HIM) have now unveiled a new technique for observing metabolic processes in the body. Their singlet-contrast MRI method employs easily-produced parahydrogen to track biochemical processes in real time. The results of their work have been published in Angewandte ...

2021-03-11

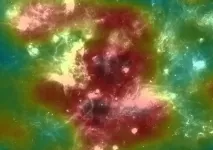

At the heart of Cygnus, one of the most beautiful constellations of the summer sky, beats a source of high-energy cosmic ray particles: the Cygnus Cocoon. An international group of scientists at the HAWC observatory has gathered evidence that this vast astronomical structure is the most powerful of our galaxy's natural particle accelerators known of up to now.

This spectacular discovery is the result of the work of scientists from the international High-Altitude Water Cherenkov (HAWC) gamma-ray observatory. Located on the slopes of the Mexican Sierra Negra volcano, the observatory records high-energy particles and photons flowing from the abyss of space. In the sky of the Northern Hemisphere, their brightest source is the region known as the Cygnus Cocoon. At the HAWC, it was established ...

2021-03-11

Geologists have long thought tectonic plates move because they are pulled by the weight of their sinking portions and that an underlying, hot, softer layer called asthenosphere serves as a passive lubricant. But a team of geologists at the University of Houston has found that layer is actually flowing vigorously, moving fast enough to drive plate motions.

In their study published in Nature Communications, researchers from the UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics looked at minute changes in satellite-detected gravitational pull within the Caribbean and at mantle tomography images - similar to a CAT Scan - of the asthenosphere under the Caribbean. They found ...

2021-03-11

Alexandria, Va., USA -- Oral mucositis and taste dysfunction (dysgeusia) occurs in nearly all patients receiving head and neck radiotherapy and tremendously affects the quality of life and treatment outcome. The study "LiCl Promotes Recovery of Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis and Dysgeusia" published in the Journal of Dental Research (JDR), investigated the hypothesis that lithium chloride (LiCl) can promote the restoration of oral mucosa integrity and taste function after radiation.

LiCl is a potent activator of a key cell signaling pathway called Wnt/β-catenin that is critical for the development, regeneration and function of many tissue types. ...

2021-03-11

BUFFALO, N.Y. - A University at Buffalo researcher's recent work on dyslexia has unexpectedly produced a startling discovery which clearly demonstrates how the cooperative areas of the brain responsible for reading skill are also at work during apparently unrelated activities, such as multiplication.

Though the division between literacy and math is commonly reflected in the division between the arts and sciences, the findings suggest that reading, writing and arithmetic, the foundational skills informally identified as the three Rs, might actually overlap in ways not previously imagined, let alone experimentally validated.

"These findings floored me," said Christopher McNorgan, PhD, the paper's author and an assistant professor in UB's Department of Psychology. "They elevate the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Skoltech team shows how Turing-like patterns fool neural networks