This raises the interesting possibility that analyzing differences between host-microbiome interactions in humans and other species, such as mice, and pinpointing individual types of bacterial that either protect or sensitize against certain pathogens, could lead to entirely new types of therapeutic approaches. However, while the intestinal microbiome composition and its effect on host immune responses have been well investigated in mice, it is not possible to study how the microbiome interacts directly with the epithelial cells lining the intestine under highly defined conditions, and thereby uncover specific bacterial strains that can induce host-tolerance to infectious pathogens.

Now, a collaborative team led by Wyss Founding Director Donald Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. at Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and Dennis Kasper, M.D. at Harvard Medical School (HMS) has harnessed the Wyss's microfluidic Organs-on-Chip (Organ Chip) technology to model the different anatomical sections of the mouse intestine and their symbiosis with a complex living microbiome in vitro. The researchers recapitulated the destructive effects of S. typhimurium on the intestinal epithelial surface in an engineered mouse Colon Chip, and in a comparative analysis of mouse and human microbiomes were able to confirm the commensal bacterium Enterococcus faecium contributes to host tolerance to S. typhimurium infection. The study is published in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology.

The project was started under a DARPA-supported "Technologies for Host Resilience" (THoR) Project at the Wyss Institute, whose goal it was to uncover key contributions to tolerance to infection by studying differences observed in certain animal species and humans. Using a human Colon Chip, Ingber's group had shown in a previous study how metabolites produced by microbes derived from mouse and human feces have different potential to impact susceptibility to infection with an enterohemorrhagic E. coli pathogen.

"Biomedical research strongly depends on animal models such as mice, which undoubtedly have tremendous benefits, but do not provide an opportunity to study normal and pathological processes within a particular organ, such as the intestine, close-up and in real-time. This important proof-of-concept study with Dennis Kasper's group highlights that our engineered mouse Intestine Chip platform offers exactly this capability and provides the possibility to study host-microbiome interactions with microbiomes from different species under highly controllable conditions in vitro," said Ingber. "Given the deep level of characterization of mouse immunology, this capability could greatly help advance the work of researchers who currently use these animals to do research on microbiome and host responses. It enables them to compare their results they obtain directly with human Intestine Chips in the future so that the focus can be on identifying features of host response that are most relevant for humans." Ingber also is the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at HMS and Boston Children's Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Engineering a mouse Intestine-on-Chip platform

In their new study, the team focused on the mouse intestinal tract. "It has traditionally been extremely difficult to model host-microbiome interactions outside any organism as many bacteria are strictly anaerobic and die in normal atmospheric oxygen conditions. Organ Chip technology can recreate these conditions, and it is much easier to obtain primary intestinal and immune cells from mice than having to rely on human biopsies," said first-author Francesca Gazzaniga, Ph.D., a Postdoctoral Fellow who works between Ingber's and Kasper's groups and spear-headed the project.

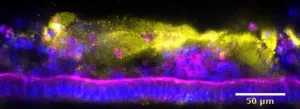

Gazzaniga and her colleagues isolated intestinal crypts from different regions of the mouse intestinal tract, including the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon, took their cells through an intermediate "organoid" step in culture in which small tissue fragments form and grow, which they then seeded into one of two parallel microfluidically perfused channels of the Wyss' Organ Chips to create region-specific Intestine Chips. The second independently perfused channel mimics the blood vasculature, and is separated from the first by a porous membrane that allows the exchange of nutrients, metabolites, and secreted molecules that intestinal epithelial cells use to communicate with vascular and immune cells.

Homing in on the pathogen

The team then honed in on S. typhimurium as a pathogen. First, they introduced the pathogen into the epithelial lumen of the engineered mouse Colon Chip and recapitulated the key features associated with the break-down of intestinal tissue integrity known from mouse studies, including the disruption of normally tight adhesions between neighboring epithelial cells, decreased production of mucus, a spike in secretion of a key inflammatory chemokine (the mouse homolog of human IL-8), and changes in epithelial gene expression. In parallel, they showed that the mouse Colon Chip supported the growth and viability of complex bacterial consortia normally present in mouse and human gut microbiomes.

Putting these capabilities together, the researchers compared the effects of specific mouse and human microbial consortia that had previously been maintained stably in the intestines of 'gnotobiotic' mice that were housed in germ-free conditions by the Kasper team. By collecting complex microbiomes from the stool of those mice, and then inoculating them into the Colon Chips, the researchers observed chip-to-chip variability in consortium composition, which enabled them to relate microbe composition to functional effects on the host epithelium. "Using 16s sequencing gave us a good sense of the microbial compositions of the two consortia, and high numbers of one individual species, Enterococcus faecium, generated by only one of them in the Colon Chip, allowed the intestinal tissue to better tolerate the infection," said Gazzaniga. "This nicely confirmed past findings and validated our approach as a new discovery platform that we can now use to investigate the mechanisms that underlie these effects as well as the contribution of vital immune cell contributions to host-tolerance, as well as infectious processes involving other pathogens."

"The mouse intestine on a chip technology provides a unique approach to understand the relationship between the gut microbiota, host immunity, and a microbial pathogen. This important interrelationship is challenging to study in the living animal because there are so many uncontrollable factors. The beauty of this system is that essentially all parameters you wish to study are controllable and can easily be monitored. This system is a very useful step forward," said Kasper, who is the William Ellery Channing Professor of Medicine and Professor of Immunology at HMS.

The researchers believe that their comparative in vitro approach could uncover specific cross-talk between pathogens and commensal bacteria with intestinal epithelial and immune cells, and that identified tolerance-enhancing bacteria could be used in future therapies, which may circumvent the problem increasing antimicrobial resistance of pathogenic bacterial strains.

INFORMATION:

By Benjamin Boettner

The study was also authored by former and present Wyss Institute researchers Diogo Camacho, Ph.D., Alexandre Dinis, Francis Grafton, Mark Cartwright, Ph.D., and Michael Super, Ph.D.; and Meng Wu, Ph.D., and Matheus Palazzo in Kasper's group. It was supported by DARPA THoR grant under award# W911NF-16-C-0050.

PRESS CONTACTS

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

Benjamin Boettner, benjamin.boettner@wyss.harvard.edu, +1 617-432-8232

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University (http://wyss.harvard.edu) uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing that are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and formation of new startups. The Wyss Institute creates transformative technological breakthroughs by engaging in high risk research, and crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers, working as an alliance that includes Harvard's Schools of Medicine, Engineering, Arts & Sciences and Design, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, University of Zurich and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.