INFORMATION:

Further information

Fungal decomposition of river organic matter accelerated by decreasing glacier cover is published in Nature Climate Change at 16:00 GMT 15 March 2021. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01004-x

The glaciers/regions that were studied were: Austria (Ödenwinkelkees, Rotmoos, Obersulzbach), Ecuador (Antisana), France (Vanoise - Chaviere and Les Allues), New Zealand (Fox Glacier, Rob Roy Glacier), Norway (Hardangervidda, Finse), United States (Alaska Boundary Range).

The manuscript has 10 authors

Sarah Fell, Lee Brown, Jonathan Carrivick - University of Leeds. Sarah was funded by a NERC Scholarship (NE/L002574/1) and all received funding from an INTERACT grant under the EU H2020 programme (GLAC-REF, Grant Agreement No 730938, Transnational Access), and the River Basin Processes and Management Cluster, School of Geography.

Kate Randall, Kirsty Matthews Nicholass, Alex Dumbrell - University of Essex. Kate and Alex were supported by a NERC grant (NE/M02086X/1).

Verónica Crespo-Pérez - Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador. The University funded Verónica under project M13434 (PUCE 2016-2017).

Sophie Cauvy-Fraunié - INRAE, France.

Eran Hood - University of Alaska Southeast, USA. Eran was funded by the Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center.

Scott Tiegs - Oakland University, USA.

The study used the facilities of the Finse Alpine Research Centre (Norway), the Obergurgl Alpine Research Centre (Austria), the Design School at the University of Leeds and the School of Life Sciences molecular ecology facilities at the University of Essex.

The authors were given permission to access field sites and work within protected areas by the Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment (research permit number: MAE-DNM-2015-0030), the Reserva Ecológica Antisana, Public Metropolitan Company of Potable Water and Sanitation of Quito (EPMAPS) and Water Projection Fund (FONAG) (Ecuador), the Parc National de la Vanoise (France), the Department of Conservation (New Zealand) and Ulvik Fjellstyre and Trond Buttingsrud (Norway).

Picture credits: Lee Brown

For further details, contact Ian Rosser in the University of Leeds press office via i.rosser@leeds.ac.uk

Melting glaciers could speed up carbon emissions into the atmosphere

2021-03-15

(Press-News.org) The loss of glaciers worldwide enhances the breakdown of complex carbon molecules in rivers, potentially contributing further to climate change.

An international research team led by the University of Leeds has for the first time linked glacier-fed mountain rivers with higher rates of plant material decomposition, a major process in the global carbon cycle.

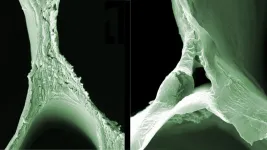

As mountain glaciers melt, water is channelled into rivers downstream. But with global warming accelerating the loss of glaciers, rivers have warmer water temperatures and are less prone to variable water flow and sediment movement. These conditions are then much more favourable for fungi to establish and grow.

Fungi living in these rivers decompose organic matter such as plant leaves and wood, eventually leading to the release of carbon dioxide into the air. The process - a key part of global river carbon cycling - has now been measured in 57 rivers in six mountain ranges across the world, in Austria, Ecuador, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United States.

The findings, funded mainly by the Natural Environment Research Council, are published today (15 March) in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Lead author Sarah Fell, of Leeds' School of Geography and water@leeds, said similar patterns and processes were discovered worldwide.

"We found increases in the rate of organic matter decomposition in mountain rivers, which can then be expected to lead to more carbon release to the atmosphere.

"This is an unexpected form of climate feedback, whereby warming drives glacier loss, which in turn rapidly recycles carbon in rivers before it is returned to the atmosphere."

The retreat of mountain glaciers is accelerating at an unprecedented rate in many parts of the world, with climate change predicted to drive continued ice loss throughout the 21st century.

However, the response of river ecosystem processes (such as nutrient and carbon cycling) to decreasing glacier cover, and the role of fungal biodiversity in driving these, remains poorly understood.

The research team used artists' canvas fabric to mimic plant materials such as leaves and grass that accumulate naturally in rivers. This was possible because the canvas is made from cotton, predominantly composed of a compound called cellulose - the world's most abundant organic polymer which is found in plant leaves that accumulate in rivers naturally.

The canvas strips were left in the rivers for approximately one month, then retrieved and tested to determine how easily they could be ripped. The strips ripped more easily as aquatic fungi colonised them, showing that decomposition of the carbon molecules proceeded more quickly in rivers which were warmer because they had less water flowing from glaciers.

The study's co-author, Professor Lee Brown, also of Leeds' School of Geography and water@leeds, explained: "Our finding of similar patterns of cellulose breakdown at sites all around the world is really exciting because it suggests that there might be a universal rule for how these river ecosystems will develop as mountains continue to lose ice. If so, we will be in much improved position to make forecasts about how river ecosystems will change in future.

Co-author Professor Alex Dumbrell, whose team at the University of Essex analysed the fungi from the river samples, added: "Our work showed that measuring a specific gene that underpins the activity of the cellulose-degrading enzyme (Cellobiohydrolase I) meant we could predict cotton strip decomposition better than using information about the abundance of fungal species themselves, which is the more commonly used approach. This opens up new routes for research to improve our predictions about changes in carbon cycling."

As algal and plant growth in glacier-fed rivers is minimised by low water temperature, unstable channels and high levels of fine sediment, plant matter breakdown can be an important fuel source to these aquatic ecosystems. In some parts of the world, such as Alaska and New Zealand, glacier-fed rivers also extend into forests that provide greater amounts of leaf litter to river food chains.

In addition, because glacier loss means less water flows through the rivers and they are less prone to changing course, it is expected that bankside plants and trees will grow more in these habitats in future, meaning even more leaf litter will accumulate in rivers. This is likely to accelerate the fungal processing of carbon in mountain rivers worldwide even more than at present.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Open door to treatment of renal fibrosis by showing that it is caused by telomere shortening

2021-03-15

Ageing is a common factor in many diseases. So, what if it were possible to treat them by acting on the causes of ageing or, more specifically, by acting on the shortening of telomeres, the structures that protect chromosomes? This strategy is being pursued by the Telomeres and Telomerase Group of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), which has already succeeded to cure pulmonary fibrosis and infarctions in mice by lengthening telomeres. Now they take a first step towards doing the same with renal fibrosis by demonstrating that short telomeres are at the origin of this disease, ...

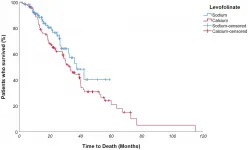

Oncotarget: Folinic acid in colorectal cancer: Esquire or fellow knight?

2021-03-15

Oncotarget published "Folinic acid in colorectal cancer: esquire or fellow knight? Real-world results from a mono institutional, retrospective study" which reported that the stock of therapeutic weapons available in metastatic colorectal cancer has been progressively grown over the years, with improving both survival and patients' clinical outcome: notwithstanding advances in the knowledge of mCRC biology, as well as advances in treatment, fluoropyrimidine antimetabolite drugs have been for 30 years the mainstay of chemotherapy protocols for this malignancy.

5-Fluorouracil seems to act differently depending on administration method: elastomer-mediated continuous infusion better inhibits Thymidylate ...

Oncotarget: A novel isoform of Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2

2021-03-15

Oncotarget published "A novel isoform of Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 promotes YAP/TEAD transcriptional activity in NSCLC cells" which reported that In this study, the authors show that a new HIPK2 isoform increases TEAD reporter activity in NSCLC cells.

They detected and cloned a novel HIPK2 isoform 3 and found that its forced overexpression promotes TEAD reporter activity in NSCLC cells.

Expressing HIPK2 isoform 3_K228A kinase-dead plasmid failed to increase TEAD reporter activity in NSCLC cells.

Next, they showed that two siRNAs targeting HIPK2 decreased HIPK2 isoform 3 and YAP protein levels in NSCLC cells.

In summary, this Oncotarget study indicates that HIPK2 isoform 3, the main HIPK2 isoform ...

Oncotarget: MicroRNA-4287 is controlling epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer

2021-03-15

The cover for issue 51 of Oncotarget features Figure 5, "miR-4287 overexpression regulates EMT in prostate cancer cell lines," published in "MicroRNA-4287 is a novel tumor suppressor microRNA controlling epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer" by Bhagirath, et al. which reported that the authors analyzed the role of miR-4287 in PCa using clinical tissues and cell lines.

Receiver operating curve analysis showed that miR-4287 distinguishes prostate cancer from normal with a specificity of 88.24% and with an Area under the curve of 0.66. Further, these authors found that miR-4287 ...

In severe COVID, cytokine "hurricane" in lung attracts damaging inflammatory cells

2021-03-15

NEW YORK, NY (March 15, 2021)--A cytokine "hurricane" centered in the lungs drives respiratory symptoms in patients with severe COVID-19, a new study by immunologists at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons suggests.

Two cytokines, CCL2 and CCL3, appear critical in luring immune cells, called monocytes, from the bloodstream into the lungs, where the cells launch an overaggressive attempt to clear the virus.

Targeting these specific cytokines with inhibitors may calm the immune reaction and prevent lung tissue damage. Currently, one drug that blocks immune responses to CCL2 is being studied in clinical trials of patients with severe COVID-19.

Survivors of severe COVID-19, the study also found, had a greater abundance of antiviral T cells in their lungs ...

Significant variation found in timing andselection of genetic tests for non--small-cell lung cancer

2021-03-15

Philadelphia, March 15, 2021 - Biomarker testing surveys specific disease-associated molecules to predict treatment response and disease progression; however its use has complicated the diagnosis of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In a new study in The Journal of Molecular Diagnosis, published by Elsevier, investigators provide for the first time a complete overview of biomarker testing, spanning multiple treatment lines, in a single cohort of patients.

Using exploratory data analysis and process-mining techniques in a real-world setting, investigators identified significant variation in test utilization and treatment. They also found that while ...

Study reveals new clues about the architecture of X chromosomes

2021-03-15

BOSTON - Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have uncovered new clues that add to the growing understanding of how female mammals, including humans, "silence" one X chromosome. Their new study, published in Molecular Cell, demonstrates how certain proteins alter the "architecture" of the X chromosome, which contributes to its inactivation. Better understanding of X chromosome inactivation could help scientists figure out how to reverse the process, potentially leading to cures for devastating genetic disorders.

Female mammals have two copies of the X chromosome in all of their cells. Each X chromosome contains many genes, but only one of the pair ...

Voltage from the parquet

2021-03-15

Ingo Burgert and his team at Empa and ETH Zurich has proven it time and again: Wood is so much more than "just" a building material. Their research aims at extending the existing characteristics of wood in such a way that it is suitable for completely new ranges of application. For instance, they have already developed high-strength, water-repellent and magnetizable wood. Now, together with the Empa research group of Francis Schwarze and Javier Ribera, the team has developed a simple, environmentally friendly process for generating electricity from a type of wood sponge, as they reported last week in the journal Science Advances.

Voltage through deformation

If you want to generate electricity ...

NASA images reveal important forests and wetlands are disappearing in Belize

2021-03-15

AUSTIN, Texas -- Using NASA satellite images and machine learning, researchers with The University of Texas at Austin have mapped changes in the landscape of northwestern Belize over a span of four decades, finding significant losses of forest and wetlands, but also successful regrowth of forest in established conservation zones that protect surviving structures of the ancient Maya.

The research serves as a case study for other rapidly developing and tropical regions of the globe, especially in places struggling to balance forest and wetland conservation with agricultural needs and food security.

"Broad-scale global studies show that tropical deforestation and wetland destruction is occurring ...

Story tips: Urban climate impacts, materials' dual approach and healing power

2021-03-15

Modeling - Urban climate impacts

Researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory have identified a statistical relationship between the growth of cities and the spread of paved surfaces like roads and sidewalks. These impervious surfaces impede the flow of water into the ground, affecting the water cycle and, by extension, the climate.

"We've shown that there is a specific mathematical shape to the relationship between a city's population and the total paved area," ORNL's Christa Brelsford said. "Using that, we examined climate model predictions and determined they correctly represent some important attributes ...