(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- Millions of people are administered general anesthesia each year in the United States alone, but it's not always easy to tell whether they are actually unconscious.

A small proportion of those patients regain some awareness during medical procedures, but a new study of the brain activity that represents consciousness could prevent that potential trauma. It may also help both people in comas and scientists struggling to define which parts of the brain can claim to be key to the conscious mind.

"What has been shown for 100 years in an unconscious state like sleep are these slow waves of electrical activity in the brain," says Yuri Saalmann, a University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology and neuroscience professor. "But those may not be the right signals to tap into. Under a number of conditions -- with different anesthetic drugs, in people that are suffering from a coma or with brain damage or other clinical situations -- there can be high-frequency activity as well."

UW-Madison researchers recorded electrical activity in about 1,000 neurons surrounding each of 100 sites throughout the brains of a pair of monkeys at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center during several states of consciousness: under drug-induced anesthesia, light sleep, resting wakefulness, and roused from anesthesia into a waking state through electrical stimulation of a spot deep in the brain (a procedure the researchers described in 2020).

"With data across multiple brain regions and different states of consciousness, we could put together all these signs traditionally associated with consciousness -- including how fast or slow the rhythms of the brain are in different brain areas -- with more computational metrics that describe how complex the signals are and how the signals in different areas interact," says Michelle Redinbaugh, a graduate student in Saalman's lab and co-lead author of the study, published today in the journal Cell Systems.

To sift out the characteristics that best indicate whether the monkeys were conscious or unconscious, the researchers used machine learning. They handed their large pool of data over to a computer, told the computer which state of consciousness had produced each pattern of brain activity, and asked the computer which areas of the brain and patterns of electrical activity corresponded most strongly with consciousness.

The results pointed away from the frontal cortex, the part of the brain typically monitored to safely maintain general anesthesia in human patients and the part most likely to exhibit the slow waves of activity long considered typical of unconsciousness.

"In the clinic now, they may put electrodes on the patient's forehead," says Mohsen Afrasiabi, the other lead author of the study and an assistant scientist in Saalmann's lab. "We propose that the back of the head is a more important place for those electrodes, because we've learned the back of the brain and the deep brain areas are more predictive of state of consciousness than the front."

And while both low- and high-frequency activity can be present in unconscious states, it's complexity that best indicates a waking mind.

"In an anesthetized or unconscious state, those probes in 100 different sites record a relatively small number of activity patterns," says Saalmann, whose work is supported by the National Institutes of Health.

A larger -- or more complex -- range of patterns was associated with the monkey's awake state.

"You need more complexity to convey more information, which is why it's related to consciousness," Redinbaugh says. "If you have less complexity across these important brain areas, they can't convey very much information. You're looking at an unconscious brain."

More accurate measurements of patients undergoing anesthesia is one possible outcome of the new findings, and the researchers are part of a collaboration supported by the National Science Foundation working on applying the knowledge of key brain areas.

"Beyond just detecting the state of consciousness, these ideas could improve therapeutic outcomes from people with consciousness disorders," Saalmann says. "We could use what we've learned to optimize electrical patterns through precise brain stimulation and help people who are, say, in a coma maintain a continuous level of consciousness."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01MH110311 and P51OD011106), the Binational Science Foundation, and the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center.

--Chris Barncard, barncard@wisc.edu

Additional Contacts:

Michelle Redinbaugh,

mredinbaugh@wisc.edu; Mohsen Afrasiabi,

afrasiabi@wisc.edu

Low doses of propylparaben - a chemical preservative found in food, drugs and cosmetics - can alter pregnancy-related changes in the breast in ways that may lessen the protection against breast cancer that pregnancy hormones normally convey, according to University of Massachusetts Amherst research.

The findings, published March 16 in the journal Endocrinology, suggest that propylparaben is an endocrine-disrupting chemical that interferes with the actions of hormones, says environmental health scientist Laura Vandenberg, the study's senior author. Endocrine ...

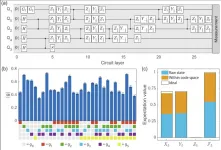

Universal fault-tolerant quantum computing relies on the implementation of quantum error correction. An essential milestone is the achievement of error-corrected logical qubits that genuinely benefit from error correction, outperforming simple physical qubits. Although tremendous efforts have been devoted to demonstrate quantum error correcting codes with different quantum hardware, previous realizations are limited to be against certain types of errors or to prepare special logical states. It remains one of the greatest and also notoriously difficult challenges to realize a universal quantum error correcting code for more than a decade.

In a new research article published in the ...

SINGAPORE, 16 March 2021 - ETC-159, a made-in-Singapore anti-cancer drug that is currently in early phase clinical trials for use in a subset of colorectal and gynaecological cancers, could also prevent some tumours from resisting therapies by blocking a key DNA repair mechanism, researchers from Duke-NUS Medical School and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore reported in the journal EMBO Molecular Medicine.

Among the many therapies used to treat cancers, inhibitors of the enzyme poly (ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP) prevent cancer cells from repairing naturally occurring DNA damage, including unwanted/harmful breaks in the DNA. When too many breaks accumulate, the cell dies.

"Some cancers have an overactive Wnt signalling pathway that may make them ...

Non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) and millimeter-wave (mmWave) are two crucial techniques of 5G to meet the explosive capacity demands. On the other hand, UAVs deployed as aerial base stations are potential to provide ubiquitous coverage and satisfy users' multifarious requirements due to their flexibility and mobility. Nevertheless, the finite onboard energy is a fundamental limit of UAVs, which can deter the performance of UAV communication networks. Therefore, the researchers Xiaowei PANG and Nan ZHAO from Dalian University of Technology, Jie TANG and Xiuyin ZHANG from South China University of Technology, and Yi QIAN from University of Nebraska-Lincoln have focused on designing energy-efficient ...

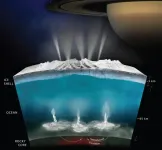

SAN ANTONIO -- March 16, 2021 -- One of the most profound discoveries in planetary science over the past 25 years is that worlds with oceans beneath layers of rock and ice are common in our solar system. Such worlds include the icy satellites of the giant planets, like Europa, Titan and Enceladus, and distant planets like Pluto.

In a report presented at the 52nd annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC 52) this week, Southwest Research Institute planetary scientist S. Alan Stern writes that the prevalence of interior water ocean worlds (IWOWs) in our solar system suggests they may be prevalent in other star systems as well, vastly expanding the conditions for planetary habitability and biological survival over time.

It has been known for many years that worlds like Earth, ...

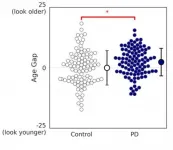

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a well-studied neurodegenerative disorder that affects between 7 and 10 million people worldwide. Despite PD being a recurrent topic in the medical literature for over 200 years, its mechanisms are largely unclear, and existing treatments are aimed at improving the patient's symptoms.

Among PD's most common symptoms are motor problems, including as tremors, slowness, and muscular rigidity. These, combined with many non-motor symptoms, cause many PD patients to develop facial abnormalities, such as face skin problems and difficulties making facial expressions. Such problems are not to be taken lightly, as one's face plays a crucial ...

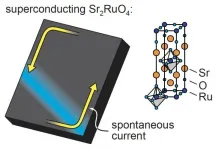

Superconductivity is a complete loss of electrical resistance. Superconductors are not merely very good metals: it is a fundamentally different electronic state. In normal metals, electrons move individually, and they collide with defects and vibrations in the lattice. In superconductors, electrons are bound together by an attractive force, which allows them to move together in a correlated way and avoid defects.

In a very small number of known superconductors, the onset of superconductivity causes spontaneous electrical currents to flow. These currents ...

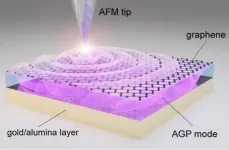

KAIST researchers and their collaborators at home and abroad have successfully demonstrated a new methodology for direct near-field optical imaging of acoustic graphene plasmon fields. This strategy will provide a breakthrough for the practical applications of acoustic graphene plasmon platforms in next-generation, high-performance, graphene-based optoelectronic devices with enhanced light-matter interactions and lower propagation loss.

It was recently demonstrated that 'graphene plasmons' - collective oscillations of free electrons in graphene coupled to electromagnetic waves of light - can be used to trap and compress optical waves inside a very thin dielectric ...

An analysis has found deforestation is severely affecting forest bird species in Colombia, home to the greatest number of bird species in the world.

University of Queensland-led research, steered by Dr Pablo Negret, analysed the impact of deforestation on 550 bird species, including 69 only found in the South American nation.

"Our study has shown an astonishing reduction in bird species habitat," Dr Negret said.

"One third of the forest bird species in Colombia have lost at least a third of their historical habitat, and that's just using the most recent data we have available - from 2015.

"Moreover, 18 per cent or 99 species have lost more than half of their historical habitat to date.

"By 2040, we expect this will increase to 38 per cent or 209 species.

"Sadly, many of those ...

A team of scientists led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has developed a device that can deliver electrical signals to and from plants, opening the door to new technologies that make use of plants.

The NTU team developed their plant 'communication' device by attaching a conformable electrode (a piece of conductive material) on the surface of a Venus flytrap plant using a soft and sticky adhesive known as hydrogel. With the electrode attached to the surface of the flytrap, researchers can achieve two things: pick up electrical signals to monitor how the plant responds to ...