(Press-News.org) Birds breathe with greater efficiency than humans due to the structure of their lungs--looped airways that facilitate air flows that go in one direction--a team of researchers has found through a series of lab experiments and simulations.

The findings will appear Fri., March 19 in the journal Physical Review Letters (to be posted between 10 and 11 a.m. EDT).

The study, conducted by researchers at New York University and the New Jersey Institute of Technology, also points to smarter ways to pump fluids and control flows in applications such as respiratory ventilators.

"Unlike the air flows deep in the branches of our lungs, which oscillate back and forth as we breathe in and out, the flow moves in a single direction in bird lungs even as they inhale and exhale," explains Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at NYU's Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences and the senior author of the paper. "This allows them to perform the most difficult and energetically costly activity of any animal: they can fly, and they can do so across whole oceans and entire continents and at elevations as high as Mount Everest, where the oxygen is extremely thin."

"The key is that bird lungs are made of looped airways--not just the branches and tree-like structure of our lungs--and we found that this leads to one-way or directed flows around the loops," adds Ristroph. "This wind ventilates even the deep recesses of the lungs and brings in fresh air."

Videos and an image depicting the work are available on Google Drive: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1ifFo9zdNIG7Pl9_7_D88zUM0d_EmEFct

The one-way flow of air in birds' breathing systems was discovered a century ago. But what had remained a mystery was an explanation of the aerodynamics behind this efficient breathing system.

To explore this, the researchers conducted a series of experiments that mimicked birds' breathing in NYU's Applied Mathematics Lab.

For the experiments, they built piping filled with water--to replicate air flow--and bent the piping to imitate the loop-like structure of birds' lungs--similar to the way freeways are connected by on-ramps and off-ramps. The researchers mixed microparticles into the water, which allowed them to track the direction of the water flow.

These experiments showed that back-and-forth motions generated by breathing were transformed into one-way flows around the loops.

"This is in essence what happens inside lungs, but now we could actually see and measure--and thus understand--what was going on," explains Ristroph, director of the Applied Mathematics Lab. "The way this plays out is that the network has loops and thus junctions, which are a bit like 'forks in the road' where the flows have a choice about which route to take."

The scientists then used computer simulations to reproduce the experimental results and better understand the mechanisms.

"Inertia tends to cause the flows to keep going straight rather than turn down a side street, which gets obstructed by a vortex," explains NJIT assistant professor and co-author Anand Oza. "This ends up leading to one-way flows and circulation around loops because of how the

junctions are hooked up in the network."

Ristroph points to several potential engineering uses for these findings.

"Directing, controlling, and pumping fluids is a very common goal in many applications, from healthcare to chemical processing to the fuel, lubricant, and coolant systems in all sorts of machinery," he observes. "In all these cases, we need to pump fluids in specific directions for specific purposes, and now we've learned from birds an entirely new way to accomplish this that we hope can be used in our technologies."

INFORMATION:

The paper's other authors were Steve Childress, a professor emeritus at the Courant Institute and co-director of the Applied Mathematics Lab; Quynh Nguyen, an NYU physics graduate student; Joanna Abouezzi and Guanhua Sun, NYU undergraduates at the time of the research; and Christina Frederick, an assistant professor at NJIT.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (DMS-1720306, DMS-1646339, DMS-1847955) and the Simons Foundation.

PHILADELPHIA - Imposter syndrome is a considerable mental health challenge to many throughout higher education. It is often associated with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem and self-sabotage and other traits. Researchers at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University wanted to learn to what extent incoming medical students displayed characteristics of imposter syndrome, and found that up to 87% of an incoming class reported a high or very high degree of imposter syndrome.

"Distress and mental health needs are critical issues among medical ...

PITTSBURGH (March 16, 2021) ... During the swarming of birds or fish, each entity coordinates its location relative to the others, so that the swarm moves as one larger, coherent unit. Fireflies on the other hand coordinate their temporal behavior: within a group, they eventually all flash on and off at the same time and thus act as synchronized oscillators.

Few entities, however, coordinate both their spatial movements and inherent time clocks; the limited examples are termed "swarmalators"1, which simultaneously swarm in space and oscillate in time. Japanese tree frogs are exemplar swarmalators: each frog changes both its location and rate of croaking ...

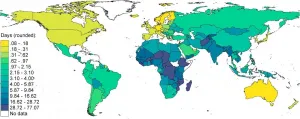

How much do people have to pay for a travel permit to another country? A research team from Göttingen, Paris, Pisa and Florence has investigated the costs around the world. What they found revealed a picture of great inequality. People from poorer countries often pay many times what Europeans would pay. The results have been published in the journal Political Geography.

Dr Emanuel Deutschmann from the Institute of Sociology at the University of Göttingen, together with Professor Ettore Recchi, Dr Lorenzo Gabrielli and Nodira Kholmatova (from Sciences Po Paris, CNR-ISTI Pisa and EUI Florence respectively) compiled a new dataset on visa costs for travel between countries worldwide. The analysis shows that on average people ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - The link between psychological stress and physical health problems generally relates to a stress-induced immune response gone wild, with inflammation then causing damage to other systems in the body. It's a predictable cascade - except in pregnancy, research suggests.

Scientists exploring the negative effects of prenatal stress on offspring mental health set out to find the immune cells and microbes in stressed pregnant mice most likely to trigger inflammation in the fetal brain - the source for anxiety and other psychological problems identified in previous research.

Instead, the researchers found two simultaneous conditions ...

Wearable electronic devices like fitness trackers and biosensors, are very promising for healthcare applications and research. They can be used to measure relevant biosignals in real-time and send gathered data wirelessly, opening up new ways to study how our bodies react to different types of activities and exercise. However, most body-worn devices face a common enemy: heat.

Heat can accumulate in wearable devices owing to various reasons. Operation in close contact with the user's skin is one of them; this heat is said to come from internal sources. Conversely, when a device is worn outdoors, sunlight acts as a massive external source of heat. These sources combined can easily raise the temperature ...

The vast majority of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 clear the virus, but those with compromised immunity--such as individuals receiving immune-suppressive drugs for autoimmune diseases--can become chronically infected. As a result, their weakened immune defenses continue to attack the virus without being able to eradicate it fully.

This physiological tug-of-war between human host and pathogen offers a valuable opportunity to understand how SARS-CoV-2 can survive under immune pressure and adapt to it.

Now, a new study led by Harvard Medical School scientists offers a look into this interplay, shedding light on the ways in which ...

A Florida State University professor's research could help quantum computing fulfill its promise as a powerful computational tool.

William Oates, the Cummins Inc. Professor in Mechanical Engineering and chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, and postdoctoral researcher Guanglei Xu found a way to automatically infer parameters used in an important quantum Boltzmann machine algorithm for machine learning applications.

Their findings were published in Scientific Reports.

The work could help build artificial neural networks ...

Prof. HUANG Weixin and ZHANG Qun from University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), together with domestic collaborators, probed into the photocatalytic oxidation of methanol on various anatase TiO2 nanocrystals. The results were published on Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Semiconductor-based photocatalysis has attracted extensive attention since its discovery, owing to its environmentally friendly production of chemical fuel utilizing solar energy.

A photocatalytic reaction consists of light absorption and charge generation within photocatalysts, ...

Nanozymes, a group of inorganic catalysis-efficient particles, have been proposed as promising antimicrobials against bacteria. They are efficient in killing bacteria, thanks to their production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Despite this advantage, nanozymes are generally toxic to both bacteria and mammalian cells, that is, they are also toxic to our own cells. This is mainly because of the intrinsic inability of ROS to distinguish bacteria from mammalian cells.

In a study published in Nature Communications, the research team led by XIONG Yujie and YANG Lihua from University of Science and Technology (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) proposed a novel method to construct efficient-while-little-toxic nanozymes.

The researchers showed that nanozymes ...

Females who are fit and healthy tend to burn more fat when they exercise than men, according to new research from a team of sports nutritionists.

The research, comprising two new studies from academics led by the University of Bath's Centre for Nutrition, Exercise & Metabolism, analysed the factors that most influenced individuals' capacity to burn body fat when undertaking endurance sports.

How the body burns fat is important to all of us for good metabolic health, insulin sensitivity and in reducing the risk of developing Type II diabetes. But, for endurance sport ...