(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - The link between psychological stress and physical health problems generally relates to a stress-induced immune response gone wild, with inflammation then causing damage to other systems in the body. It's a predictable cascade - except in pregnancy, research suggests.

Scientists exploring the negative effects of prenatal stress on offspring mental health set out to find the immune cells and microbes in stressed pregnant mice most likely to trigger inflammation in the fetal brain - the source for anxiety and other psychological problems identified in previous research.

Instead, the researchers found two simultaneous conditions in response to stress that made them realize just how complex the cross-talk between mom and baby is during gestation: Immune cells in the placenta and uterus were not activated, but significant inflammation was detected in the fetal brain.

They also found that prenatal stress in the mice led to reductions in gut microbial strains and functions, especially those linked to inflammation.

"I thought it was going to be a fairly straightforward tale of maternal inflammation, changes in microbes and fetal inflammation. And while the changes in microbes are there, the inflammation part is more complex than I had anticipated," said Tamar Gur, senior author of the study and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral health, neuroscience, and obstetrics and gynecology at The Ohio State University.

"The complex interplay between the stress response and the immune system is dysregulated by stress, which is problematic for the developing fetus. There are key changes during this critical window that can help shape the developing brain, so we want to figure out how we could potentially intervene to help regulate these systems."

The study was published recently in Scientific Reports.

Most attention paid to the negative effects of prenatal stress on offspring mental health focus on disruptive major life events or exposure to disaster, but evidence also suggests that up to 84% of pregnant women experience some sort of stress.

In a previous study, Gur's lab found that prenatal stress's contributions to life-long anxiety and cognitive problems in mouse offspring could be traced to changes in microbial communities in both mom and baby.

Gur focuses on the intrauterine environment in her search for factors that increase the risk for prenatal stress's damaging effects, and this newer study opened her eyes to how complicated that environment is.

"The dogma would be that we're going to see an influx of immune cells to the placenta. The fact that it's suppressed speaks to the powerful anti-inflammatory response of the mom. And that makes sense - a fetus is basically a foreign object, so in order to maintain pregnancy we need to have some level of immunosuppression," said Gur, also an investigator in Ohio State's Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research and a maternal-fetal psychiatrist at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

"We want to figure out what is at the interface between mom and baby that is mediating the immunosuppressive effect on the maternal side and the inflammation on the fetal side. If we can get at that, we'll get really important keys to understanding how best to prevent the negative impact of prenatal stress."

Prevention could come in the form of prebiotics or probiotics designed to boost the presence of beneficial microbes in the GI tract of pregnant women. Maternal microbes affect the brains and immune systems of developing offspring by producing a variety of chemicals the body uses to manage physiological processes.

"I think microbes hold really important clues and keys, making them a tantalizing target for intervention. We can do things about individuals' microbes to benefit both mom and baby," Gur said.

To mimic prenatal stress during the second and early third trimesters, pregnant mice in her lab are subjected to two hours of restraint for seven days to induce stress. Control mice are left undisturbed during gestation.

In this recent study, the researchers found stress in mice activated steroid hormones throughout the body - the sign of a suppressed immune system - and resulted in lower-than-expected populations of immune cells in reproductive tissue, suggesting that the uterus was effectively resisting the effects of the stress.

An examination of colon contents showed differences in microbial communities between stressed and non-stressed mice, with one family of microbes that influences immune function markedly decreased in stressed mice. The researchers found that stress showed few signs of gene-level changes in the colon that could let bacteria escape to the bloodstream - one way that microbes interfere with body processes.

"There are absolutely changes in microbes that might help explain key pathways that are important for health and the immune system, especially when it comes to the placenta and the mom's immune system," Gur said.

In future studies, her lab will examine immune cells in the fetal brain and monitor how gene expression changes in cells in the placenta in response to stress. She is also leading an ongoing observational study in women, tracking microbes, inflammation and stress levels during and after pregnancy.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and startup funds from Ohio State. Co-authors, all from Ohio State, include Adrienne Antonson, Morgan Evans, Jeffrey Galley, Helen Chen, Therese Rajasekera, Sydney Lammers, Vanessa Hale and Michael Bailey.

Contact:

Tamar Gur,

tamar.gur@osumc.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell,

Caldwell.151@osu.edu

Wearable electronic devices like fitness trackers and biosensors, are very promising for healthcare applications and research. They can be used to measure relevant biosignals in real-time and send gathered data wirelessly, opening up new ways to study how our bodies react to different types of activities and exercise. However, most body-worn devices face a common enemy: heat.

Heat can accumulate in wearable devices owing to various reasons. Operation in close contact with the user's skin is one of them; this heat is said to come from internal sources. Conversely, when a device is worn outdoors, sunlight acts as a massive external source of heat. These sources combined can easily raise the temperature ...

The vast majority of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 clear the virus, but those with compromised immunity--such as individuals receiving immune-suppressive drugs for autoimmune diseases--can become chronically infected. As a result, their weakened immune defenses continue to attack the virus without being able to eradicate it fully.

This physiological tug-of-war between human host and pathogen offers a valuable opportunity to understand how SARS-CoV-2 can survive under immune pressure and adapt to it.

Now, a new study led by Harvard Medical School scientists offers a look into this interplay, shedding light on the ways in which ...

A Florida State University professor's research could help quantum computing fulfill its promise as a powerful computational tool.

William Oates, the Cummins Inc. Professor in Mechanical Engineering and chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering, and postdoctoral researcher Guanglei Xu found a way to automatically infer parameters used in an important quantum Boltzmann machine algorithm for machine learning applications.

Their findings were published in Scientific Reports.

The work could help build artificial neural networks ...

Prof. HUANG Weixin and ZHANG Qun from University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), together with domestic collaborators, probed into the photocatalytic oxidation of methanol on various anatase TiO2 nanocrystals. The results were published on Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Semiconductor-based photocatalysis has attracted extensive attention since its discovery, owing to its environmentally friendly production of chemical fuel utilizing solar energy.

A photocatalytic reaction consists of light absorption and charge generation within photocatalysts, ...

Nanozymes, a group of inorganic catalysis-efficient particles, have been proposed as promising antimicrobials against bacteria. They are efficient in killing bacteria, thanks to their production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Despite this advantage, nanozymes are generally toxic to both bacteria and mammalian cells, that is, they are also toxic to our own cells. This is mainly because of the intrinsic inability of ROS to distinguish bacteria from mammalian cells.

In a study published in Nature Communications, the research team led by XIONG Yujie and YANG Lihua from University of Science and Technology (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) proposed a novel method to construct efficient-while-little-toxic nanozymes.

The researchers showed that nanozymes ...

Females who are fit and healthy tend to burn more fat when they exercise than men, according to new research from a team of sports nutritionists.

The research, comprising two new studies from academics led by the University of Bath's Centre for Nutrition, Exercise & Metabolism, analysed the factors that most influenced individuals' capacity to burn body fat when undertaking endurance sports.

How the body burns fat is important to all of us for good metabolic health, insulin sensitivity and in reducing the risk of developing Type II diabetes. But, for endurance sport ...

Research led by the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge has identified a material that could help tackle speed and energy, the two biggest challenges for computers of the future.

Research in the field of light-based computing - using light instead of electricity for computation to go beyond the limits of today's computers - is moving fast, but barriers remain in developing optical switching, the process by which light would be easily turned 'on' and 'off', reflecting or transmitting light on-demand.

The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that a material known as Ta2NiSe5 could switch between a window and a mirror in a quadrillionth of a second when struck by a short laser pulse, paving the way for the development ...

The bacterial equivalent of a traffic jam causes multilayered biofilms to form in the presence of antibiotics, shows a study published today in eLife.

The study reveals how the collective behaviour of bacterial colonies may contribute to the emergence of antibiotic resistance. These insights could pave the way to new approaches for treating bacterial infections that help thwart the emergence of resistance.

Bacteria can acquire resistance to antibiotics through genetic mutations. But they can also defend themselves via collective behaviours such as joining together ...

The inclusion of a special new perovskite layer has enabled scientists to create a "spin-polarized LED" without needing a magnetic field or extremely low temperatures, potentially clearing the path to a raft of novel technologies.

Details of the research conducted at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the University of Utah appear in the journal Science.

Researchers at NREL and around the world have been investigating the use of perovskite semiconductors for solar cells that have proven to be highly efficient at converting sunlight to electricity. Since a solar cell is one of the most demanding applications of any semiconductor, scientists are discovering other uses exist as well.

"We are exploring the fundamental properties of metal-halide ...

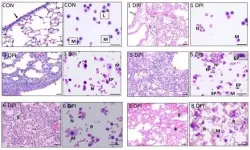

Philadelphia, March 16, 2021 - A significant proportion of hospitalized patients with influenza develop complications of acute respiratory distress syndrome, driven by virus-induced cytopathic effects as well as exaggerated host immune response. Reporting in The American Journal of Pathology, published by Elsevier, investigators have found that treatment with an immune receptor blocker in combination with an antiviral agent markedly improves survival of mice infected with lethal influenza and reduces lung pathology in swine-influenza-infected piglets. Their research also provides insights into the optimal timing of treatment to prevent acute lung injury.

Previously, the investigators found ...