Viruses adapt to 'language of human cells' to hijack protein synthesis

Findings may boost design of antiviral treatments, gene therapies and vaccines

2021-03-16

(Press-News.org) The first systematic study of its kind describes how human viruses including SARS-CoV-2 are better adapted to infecting certain types of tissues based on their ability to hijack cellular machinery and protein synthesis.

Carried out by researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), the findings could help the design of more effective antiviral treatments, gene therapies and vaccines. The study is published today in the journal Cell Reports.

Living organisms make proteins inside their cells. Each protein consists of single units of amino acids which are stitched together according to instructions encoded within DNA. The basic units of these instructions are known as a codons, each of which corresponds to a specific amino acid. A synonymous codon is when two or more codons result in cells producing the same amino acid.

"Different tissues use different languages to make proteins, meaning they preferentially use some synonymous codons over others. We know this because tRNAs, the molecules responsible for recognising codons and sticking on the corresponding amino acid, have different abundances in different tissues," explains Xavier Hernandez, first author of the study and researcher at the CRG.

When a virus infects an organism, it needs to hijack the machinery of the host to produce its own proteins. The researchers set out to investigate whether viruses were specifically adapted to using the synonymous codons used preferentially by the tissues they infect.

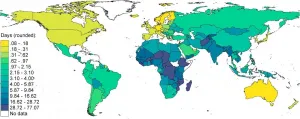

The researchers downloaded the publicly available protein sequences of all known human viruses and studied their codon usage. Based on the known tRNA abundances in different tissues, they then determined how well adapted all 502 human-infecting viruses were at infecting 23 different human tissues.

Viral proteins expressed during the early infection stage were better adapted to hijacking the host's protein-making machinery. According to Xavier Hernandez, "well adapted viruses start by using the preferred language of the cell but after taking full control they impose a new one that meets its own needs. This is important because viruses are used in gene therapy to treat genetic diseases and, if we want to correct a mutation in one tissue, we should modify the virus to be optimal for that particular tissue."

The researchers then took a closer look at how different respiratory viruses are adapted to infecting specific tissues based on their codon usage. They studied four different coronaviruses - SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and the bat coronavirus that is most closely related to SARS-CoV-2 - as well as the common flu-causing influenza A virus H1N1.

They found that SARS-CoV-2 adapted its codon usage to lung tissue, the gastrointestinal tract and the brain. As this aligns with known COVID-19 symptoms such as pneumonia, diarrhoea or loss of smell and taste, the researchers hypothesise future treatments and vaccines could take this factor into account to generate immunity in these tissues.

"Out of the respiratory viruses we took a close look at, SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that is most highly adapted to hijacking the protein synthesis machinery of its host tissue, but not more so than influenza or the bat coronavirus. This suggests that factors other than translational efficiency play an important role in infection, for example the ACE2 receptor expression or the immune system," concludes Xavier Hernandez.

The researchers next steps include further developing a biotechnological tool to design optimised protein sequences containing codons adapted to the tissue of interest, which may be useful for the development of gene therapies.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-16

When scientists at the Institute of Science and Technology (IST) Austria looked at developing zebrafish embryos, they observed an abrupt and dramatic change: within just a few minutes, the solid-like embryonic tissue becomes fluid-like. What could cause this change and, what is its role in the further development of the embryo? In a multidisciplinary study published in the journal Cell, they found answers that could change how we look at key processes in development and disease, such as tumor metastasis.

To learn more about how a tiny bunch of cells develops into complex systems ...

2021-03-16

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- In the past few years, several medications have been found to be contaminated with NDMA, a probable carcinogen. This chemical, which has also been found at Superfund sites and in some cases has spread to drinking water supplies, causes DNA damage that can lead to cancer.

MIT researchers have now discovered a mechanism that helps explain whether this damage will lead to cancer in mice: The key is the way cellular DNA repair systems respond. The team found that too little activity of one enzyme necessary for DNA repair leads to much higher cancer rates, while too much activity can produce tissue damage, especially in the liver, which can be fatal.

Activity ...

2021-03-16

Several oceans' worth of ancient water may reside in minerals buried below Mars' surface, report researchers. The new study, based on observational data and modeling, shows that much of the red planet's initial water - up to 99% - was lost to irreversible crustal hydration, not escape to space. The findings help resolve the apparent contradictions between predicted atmospheric loss rates, the deuterium to hydrogen ratio (D/H) of present-day Mars and the geological estimates of how much water once covered the Martian surface. Ancient Mars was a wet planet - dry riverbeds and relic shorelines record a time when vast volumes of liquid water flowed across the surface. Today, ...

2021-03-16

Birds breathe with greater efficiency than humans due to the structure of their lungs--looped airways that facilitate air flows that go in one direction--a team of researchers has found through a series of lab experiments and simulations.

The findings will appear Fri., March 19 in the journal Physical Review Letters (to be posted between 10 and 11 a.m. EDT).

The study, conducted by researchers at New York University and the New Jersey Institute of Technology, also points to smarter ways to pump fluids and control flows in applications such as respiratory ventilators.

"Unlike the air flows deep in the branches of our lungs, which oscillate back and forth as we breathe in and out, the flow moves in a single direction in ...

2021-03-16

PHILADELPHIA - Imposter syndrome is a considerable mental health challenge to many throughout higher education. It is often associated with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem and self-sabotage and other traits. Researchers at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University wanted to learn to what extent incoming medical students displayed characteristics of imposter syndrome, and found that up to 87% of an incoming class reported a high or very high degree of imposter syndrome.

"Distress and mental health needs are critical issues among medical ...

2021-03-16

PITTSBURGH (March 16, 2021) ... During the swarming of birds or fish, each entity coordinates its location relative to the others, so that the swarm moves as one larger, coherent unit. Fireflies on the other hand coordinate their temporal behavior: within a group, they eventually all flash on and off at the same time and thus act as synchronized oscillators.

Few entities, however, coordinate both their spatial movements and inherent time clocks; the limited examples are termed "swarmalators"1, which simultaneously swarm in space and oscillate in time. Japanese tree frogs are exemplar swarmalators: each frog changes both its location and rate of croaking ...

2021-03-16

How much do people have to pay for a travel permit to another country? A research team from Göttingen, Paris, Pisa and Florence has investigated the costs around the world. What they found revealed a picture of great inequality. People from poorer countries often pay many times what Europeans would pay. The results have been published in the journal Political Geography.

Dr Emanuel Deutschmann from the Institute of Sociology at the University of Göttingen, together with Professor Ettore Recchi, Dr Lorenzo Gabrielli and Nodira Kholmatova (from Sciences Po Paris, CNR-ISTI Pisa and EUI Florence respectively) compiled a new dataset on visa costs for travel between countries worldwide. The analysis shows that on average people ...

2021-03-16

COLUMBUS, Ohio - The link between psychological stress and physical health problems generally relates to a stress-induced immune response gone wild, with inflammation then causing damage to other systems in the body. It's a predictable cascade - except in pregnancy, research suggests.

Scientists exploring the negative effects of prenatal stress on offspring mental health set out to find the immune cells and microbes in stressed pregnant mice most likely to trigger inflammation in the fetal brain - the source for anxiety and other psychological problems identified in previous research.

Instead, the researchers found two simultaneous conditions ...

2021-03-16

Wearable electronic devices like fitness trackers and biosensors, are very promising for healthcare applications and research. They can be used to measure relevant biosignals in real-time and send gathered data wirelessly, opening up new ways to study how our bodies react to different types of activities and exercise. However, most body-worn devices face a common enemy: heat.

Heat can accumulate in wearable devices owing to various reasons. Operation in close contact with the user's skin is one of them; this heat is said to come from internal sources. Conversely, when a device is worn outdoors, sunlight acts as a massive external source of heat. These sources combined can easily raise the temperature ...

2021-03-16

The vast majority of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 clear the virus, but those with compromised immunity--such as individuals receiving immune-suppressive drugs for autoimmune diseases--can become chronically infected. As a result, their weakened immune defenses continue to attack the virus without being able to eradicate it fully.

This physiological tug-of-war between human host and pathogen offers a valuable opportunity to understand how SARS-CoV-2 can survive under immune pressure and adapt to it.

Now, a new study led by Harvard Medical School scientists offers a look into this interplay, shedding light on the ways in which ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Viruses adapt to 'language of human cells' to hijack protein synthesis

Findings may boost design of antiviral treatments, gene therapies and vaccines